Charles Defodon

Charles-Jacques Defodon (14 May 1832 – 18 February 1891) was a French educationist who had great influence on primary education in France in the later part of the 19th century. He helped initiate many reforms, including improvements to the education of girls. His pedagogical books shed light on what a committed republican thought children should and should not be taught.

Charles-Jacques Defodon | |

|---|---|

| Born | 14 May 1832 Rouen, France |

| Died | 18 February 1891 (aged 58) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Teacher |

Life

Charles-Jacques Defodon was born in Rouen on 14 May 1832. He was a brilliant pupil at secondary school in Rouen, then went on to the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris. He was an independent teacher in Paris from 1853 to 1863. During this period he was the secretary of Victor Cousin for some time. In 1864 the publisher Louis Hachette gave him the position as assistant to M. Barrau in drafting the General Manual of Primary Education. Defodon would devote the rest of his career to primary education, and became a highly respected leader in this field.[1]

After Barrau died in 1865 he became responsible for the General Manual. At the time primary education was in poor shape in France, and many reforms were needed to rejuvenate it. Defodon combined prudence with vision. Thus he wanted to create two schools to train the senior teaching and administrative staff of the primary education system. He also arranged for an exhibition on schools at the International Exposition of 1867, which was a great success. Defodon was professor at the teacher training school of Auteuil (1872–79), Librarian of the Educational Museum (1879–85) and primary inspector in Paris (1885–91).[1]

Defodon was associated with the Ami de l'enfance, the organ of the French maternal educational system, which he co-edited with Pauline Kergomard.[1] In 1884 the French Chamber's budget commission considered eliminating all inspectresses general of nursery schools. The L'Ami de l'enfance raised the alarm. Defodon praised the inspectorate as a French tradition that made use of women's distinctive maternal talents. Caroline de Barrau noted that nursery schools had been founded as an initiative of women which the state then chose to support. She disparaged the regime by comparison to its predecessors, who had introduced inspectresses general. The unsatisfactory compromise was to dismiss or retire four of the inspectresses and retain the other four.[2]

Charles-Jacques Defodon was a member of the Higher Education Council from 1888 until his death in Paris on 18 February 1891.[1]

Views

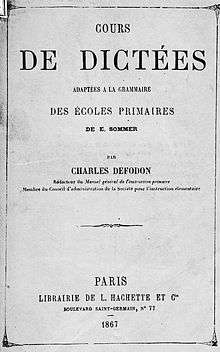

Defodon's views changed over time. The 1867 version of his dictées (passages the students would write from dictation) for primary students had no references to exercise and did not mention the human body or its functions. The 1880 version includes several passages about manual professions, and describes at length the human body, its parts and functions. It has several passages depicting girls and boys exercising to improve their strength and agility. Defodon wrote in a passage on "Legs" that although weak at first they gradually "acquire the firmness and strength necessary to permit him to walk ... run, and finally jump and dance. All our organs are involved. Exercise alone develops power, flexibility, elasticity and energy".[3]

Defodon was concerned about the decline in exports of French crafts, an area where France had once been supreme in Europe.[4] In his 1880 book of dictées Defodon told pupils:

A person's profession is nothing other than the work to which one dedicates oneself in order to earn one's living. ... We call this a métier. There are no foolish métiers, there are only foolish people. All honest professions are honorable. Laziness alone merits contempt. The bread that one eats by the sweat of his brow is worth a hundred times that which comes from alms. When one has two robust arms and good health, it is shameful to give onself up to lazing about. ... [Idleness] leads sometimes to prison, and surely to the hospital.[4]

In 1881 Hachette published a new edition of François Fénelon's classic work De l'éducation des filles, annotated by Defodon. As a Republican, Defodon rejected the emphasis that Fénelon placed on piety but accepted much of what he taught about the personality on women and their domestic role. Defodon thought that Fénelon was too restrictive in instruction of women on subjects like history, which were important in developing their patriotism.[5]

In 1892 the Committee on Primary Teaching proposed to ban literary history from the superior primary school curricula. Defodon supported this. He wrote that "any pursuit of curiosity or erudition was to be banned from elementary school."[6] Defodon was not comfortable with realistic school plays. He said that even when a work was ridiculing vices, the audience could still be seduced and deceived by them. Further, the authors of comic plays often made fun of characters and things that did not deserve reproach.[7] He disliked applause from the audience, since it might make the students presenting a play presumptuous.[8]

Publications

- Defodon, Charles (1868). Promenade à l'exposition scolaire de 1867: Souvenir de la visite des instituteurs. Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferté, Henri; Defodon, Charles (1869). Les Expositions scolaires départementales de 1868. L. Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Demkès, Auguste; Defodon, Charles (1872). Almanach de l'instruction primaire pour 1872. sn.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles (1872). Cours de dictées, convenant à toutes les méthodes d'enseignement grammatical et spécialement adaptées à la grammaire des écoles primaires de E. Sommer. Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles (1880). Petites dictées pour les écoles rurales, textes et explications, par Charles Defodon,... et J. Vallée,... Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salignac de la Mothe Fénelon, François de; Defodon, Charles (1881). De l'éducation des filles. Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles; Buisson, Ferdinand; Bagnaux, J. de; Bonaventure Berger; Eugène Brouard (1881). Devoirs d'écoliers étrangers, recueillis à l'Exposition universelle de Paris (1878) et mis en ordre par MM. de Bagnaux, Berger, Brouard, Buisson et Defodon,... Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles; Guillaume, J.; Kergomard, Pauline (1883). Lectures pédagogiques à l'usage des écoles normales primaires ... Hachette & Cie.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles (1883). Une Lettre de Jean-Paul. Toto historien. L'Éléphant. La Sauterelle et la Fourmi (fable). Qui est-ce qui a eu tort ?. Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles; Brouard, Eugène (1885). Manuel du certificat d'aptitude pédagogique. Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brouard, Eugène; Defodon, Charles (1887). Inspection des écoles primaires: ouvrage a l'usage des inspecteurs... Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles (1887). De-ci, de-là. Fables, contes, petits récits. [With illustrations.].CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles (1888). Regardez, mais n'y touchez pas ! par C. Defodon. Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles (1889). Les Expositions scolaires départementales. Impr. nationale.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brouard, Eugène; Defodon, Charles (1890). Questions de pédagogie: théorique et practique ... Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles (1890). Cours de dictées convenant aux méthodes les plus usitées d'enseignement grammatical, suivi de dictées données dans les examens, ... Onzième édition... Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles; Doré, Gustave; Wogel (1895). Petit choix de fables: tirées de nos principaux fabulistes. Librairie Hachette et Cie.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Defodon, Charles (1906). Choix de fables de La Fontaine, Florian et autres auteurs, publiées avec un commentaire et des notes biographiques et explicatives, à l'usage des écoles primaires... 10e édition. Hachette.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- Buisson 1911.

- Clark 2000, p. 54.

- Tilburg 2009, p. 55.

- Tilburg 2009, p. 29.

- Clark 1984, p. 19.

- Chapin 2011, p. 73.

- Chapin 2011, p. 105.

- Chapin 2011, p. 126.

Sources

- Buisson, Ferdinand (1911). "Defodan (Charles-Jacques)". Dictionnaire de pédagogie. Retrieved 2014-11-20.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapin, Emmanuelle Sandrine (2011). Discriminating Democracy: Theater and Republican Cultural Policy in France, 1878-1893. Stanford University. STANFORD:kw083cw0939. Retrieved 2014-11-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Linda L. (1984). Schooling the Daughters of Marianne: Textbooks and the Socialization of Girls in Modern French Primary Schools. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-787-8. Retrieved 2014-11-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Linda L. (2000-12-21). The Rise of Professional Women in France: Gender and Public Administration since 1830. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-42686-2. Retrieved 2014-10-23.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tilburg, Patricia A. (2009). Colette's Republic: Work, Gender, and Popular Culture in France, 1870-1914. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-571-2. Retrieved 2014-11-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)