Chandabhoy Galla Case

The Chandabhoy Galla Case set a significant precedent on the issue of a human's claim to being infallible, immaculate, executor of God's will, and trusteeship of God's funds. The case was filed in 1917, during the British rule of India, by Sir Thomas Strangman, the Advocate General of Bombay, at the behest of Adamjee Peerbhoy's family against the 51st Dai al-Mutlaq of the Dawoodi Bohra, Taher Saifuddin. In 1921, Saifuddin won the case on basis of the belief that Imam, as representative of the Prophet and through him the representative of God, having withdrawn from the world, must entrust someone to represent them-- to be a deity on earth-- the Dai al-Mutlaq (and hence Saifuddin), in accordance with the Tayyibi religious belief, is that sole representative.

The trusteeship of the money donated via a Galla (lit. 'money safe') kept near the tomb of Chandabhoy in Bombay, who was revered as a miraculous Saint, was challenged on the plea of improper chain of succession from 47th Dai al-Mutlaq, Abdul Qadir Najmuddin's appointment. Issues pertaining to the office of Dai al-Mutlaq raised during the case, however; were of greater importance than the trusteeship of the Galla itself.[1][2] Sir Thomas Strangman observes in his book Indian Courts and Characters that the case is remarkable not only for its length, but for the amazing claims put forward on behalf of the 'Mullaji' (Taher Saifuddin), the like of which have never been put forward in any Court of Law.[3]

Had Abdul Qadir Najmuddin's appointment not upheld by the court, validity of the subsequent Duat al-Mutlaqeen could be questioned, and by extension, their trusteeship of all religious properties. Justice Marten based his judgement on religious texts to hold that all properties (in respect of which the declaration was sought) were devoted to charitable purposes, and that the Mullaji (Taher Saifuddin) was sole trustee thereof, and also that, despite his infallibility, the Mullaji remained accountable to the Court of Law:[4][5]

- "...high-ranking people could be trusted not to commit criminal breach of trust; but that did not mean that they were beyond the pale of the law. For example, His Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury, could not conceivably commit a criminal offence; but he was nevertheless subject to the criminal law, and this fact involved no slur. So, too, in theory the Mullaji Saheb was amenable to the criminal and civil law of this country, though it was unthinkable that he would commit any offence. But the existence of this civil restraint is no more a slur upon an honest trustee, than the existence of criminal restraint is upon an honest citizen. The test of a trust is not whether the alleged trustee can ever commit a breach of trust, which is what the defendants' contention in effect amounts to."

Upon conclusion of the case, Strangman noted:[4]

- "Looking back on the proceedings, I think what impressed me the most, even more than the extravagance of the claims, was the personality of the Mullaji, a frail looking figure possessed nevertheless of an iron will, great determination, and organising capacity. At the time he assumed office the administration must have been extremely slack. Yet he managed in a very few years not only to pull the administration together but to obtain a hold upon his followers greater perhaps than that of any of his predecessors."

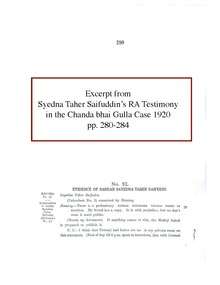

During Taher Saifuddin's testimony, he clarified about existence of knowledge classes of Zahir, Tawil, and Haqiqat: First two of the three are known to many but the third, Haqiqat, contains religious truths known to a very few. And an even higher class of knowledge which is with the Dai al-Mutlaq exclusively that they pass on only to their successors.[6]

A similar case was brought to the court of Mughal emperor, Jalaluddin Akbar, in 1591, as Sulayman ibn Hasan challenged Dawood Bin Qutubshah's accession. After much deliberation, Akbar eventually issued a royal farman (lit. 'decree') in favor of Qutub Shah, instead.[7][8][9] In another instance in 2014, succession of Mufaddal Saifuddin was contested by an opposing faction led by Khuzaima Qutbuddin, Taher Saifuddin's son, who moved the Bombay High Court to protract the case[10][11] despite lack of mainstream recognition.[12][13]

References

- Blank, Jonah (2001). Mullahs on the Mainframe: Islam and Modernity Among the Daudi Bohras. p. 236. ISBN 0226056767 – via books.google.com.

- Daftary, Farhad, ed. (2010). Modern History of the Ismailis: Continuity and Change in a Muslim Community. ISBN 0857735268 – via books.google.com.

- Strangman, Thomas. Indian Courts and Characters – via books.google.com.

- "Mullaji Case (Chandabhoy Gulla Case)-19l8-19l9". 1919.

- The Advocate General Of Bombay vs Yusufalli Ebrahim on 19 March, 1921 (High Court of Bombay 1922). Text

- The Advocate General Of Bombay vs Yusufalli Ebrahim on 19 March, 1921, 52 Justice Marten, 280-284 (High Court of Bombay 1922).

- "Unique case: From Akbar's court in 1591 to Bombay HC".

- "History of Duat Mutlakin's of Ahmedabad". Archived from the original on 10 February 2001.

- Hassanally, Yusuf Mamujee (2017). "The 27th Dai al-Mutlaq, Ad-Da'il Ajal Syedna Dawood Burhanuddin bin Qutubshah bin Khwaja bin Ali". Gems of History: A Brief History of Doat Mutlaqeen. Colombo: Alvazaratus Saifiyah. pp. 110–115.

- Mawani, Rizwan (30 January 2014). "The Intricacies of Succession: Two Claimants Emerge for Dawoodi Bohra Leadership". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Bhutia, Lhendup G (3 February 2020). "Uncertainty Among the Bohras". openthemagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020.

- Waring, Kate (15 August 2014). "UK Charity Commission's View regarding The Dawat-e-Hadiyah Trust". Herbert Smith Freehills Solicitors and Nabarro Solicitors (Charity Commission).

- Schleifer, S Abdallah, ed. (2019). "The Muslim 500: The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims" (PDF). themuslim500.com. Jordan: The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre. ISBN 9789957635459. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.