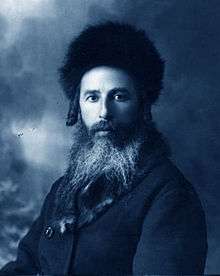

Chaim Yehuda Leib Auerbach

Chaim Yehuda Leib Auerbach (1883 – 26 September 1954) was a Haredi rabbi and roshei yeshiva of Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva, a landmark Jerusalem institution specializing in Talmudic and kabbalah studies for Ashkenazi scholars that he helped found in 1906. The yeshiva still exists today. Known for his great love and personal sacrifice for Torah and Torah scholars, Auerbach raised sons who also became great scholars — including his eldest son, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, a preeminent posek of the mid- to late-twentieth century.

Rabbi Chaim Yehuda Leib Auerbach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | Chaim Yehuda Leib Auerbach 1883 |

| Died | 26 September 1954 |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Spouse | Tzivia Porush |

| Children | Shlomo Zalman Avraham Dov Eliezer Refoel Dovid Leah (wife of Rabbi Shalom Schwadron) Malka Rochel (wife of Rabbi Simcha Bunim Leizerson) |

| Parents | Rabbi Avraham Dov Auerbach |

| Position | Rosh yeshiva |

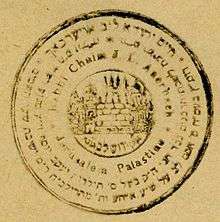

| Yeshiva | Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva |

| Began | 1906 |

| Ended | 1954 |

| Buried | Har HaMenuchot |

| Residence | Jerusalem |

Family

Auerbach was descended from an illustrious line of Hasidic leaders. His father was Rabbi Avraham Dov Auerbach, the Admor of Chernowitz-Chmielnik, Poland, who was a son-in-law of Rabbi Tzvi Halberstam, son of the Divrei Chaim of Sanz. Rabbi Avraham Dov was a son of Rabbi Yehuda Dov Auerbach of Tsfat and Jerusalem, who was a son of Rabbi Yoel Faivel Stein, who was a son-in-law of Rabbi Avraham Dov of Chmielnik, a son-in-law of Rabbi Jacob Joseph of Polonne, the Baal Shem Tov's most prominent disciple and author of Toldos Yaakov Yosef on Hasidic thought.[1]

Auerbach married Tzivya, the daughter of Jerusalem community leader Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Porush, who founded the Jerusalem neighborhood of Sha'arei Hesed.[2] Their first son, Shlomo Zalman, named after his maternal grandfather,[3] was the first child born in Sha'arei Hesed.[4]

Lifestyle

Like other Jerusalem families in the post-World War I Yishuv, the Auerbachs lived in dire poverty. Their home in the Nachalas Tzadok neighborhood of Jerusalem (adjacent to Shaarei Chesed) lacked a refrigerator and an icebox; instead, food for Shabbat was kept in a box tied to a rope, which was lowered into the well outdoors to keep cold.[5] Their son, Shlomo Zalman, once remarked, "In my youth, I never felt full." His brother, Rabbi Avraham Dovid Auerbach, said, "In our home, I never once ate a whole egg. My mother would scramble an egg with a bit of flour and divide it among three children. A whole egg? Who ever heard of such a thing?"[6]

Though consigned to poverty, Auerbach and his wife valued Torah and Torah scholars above all else. To that end, they sought only serious Torah scholars for their daughters rather than men of means or reputation.[7] They also were willing to sacrifice all to feed and support the hundreds of young men learning at Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva. Often Auerbach pledged his own family's belongings, including the furniture, as security against loans which he took for the upkeep of the yeshiva students.[8]

Auerbach was given to holy ways. Often he rolled in the snow and wore sackcloth under his clothing to mortify his flesh, in the way of hidden tzaddikim.[9][10] He would retire early in the evening and then rise before midnight, learning until dawn. Then he would recite the Shema and go to bed again until it was time for the morning prayers. Some of his neighbors criticized his penchant for "going to bed early and getting up late," not realizing that while they slept, he was learning Torah.[9]

Collecting sefarim (holy books) was one of Auerbach's passions. Though sefarim in the 1920s were extremely expensive, Auerbach nevertheless managed to build up a large library of his own. He did so primarily in the period between World Wars, when Palestine was ravaged by famine and people sold off their sefarim by the wagonload to buy bread. Living on a bare minimum, Auerbach managed to purchase many sefarim in this way.[11]

Auerbach authored a Torah commentary called Chacham Lev.[10]

A month before his death, he had a severe heart attack and lapsed into semi-consciousness. He died on 26 September 1954 (28 Elul 5714).[10]

Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva

The idea of founding Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva came to Auerbach one night in a dream. He awoke from the strange dream and tried to fall asleep again, only to dream the same thing a second time. He decided to get dressed and go out to consult with his friend, Rabbi Shimon Tzvi Horowitz, about the strange vision. As he walked toward Horowitz's home in the Knesset Yisrael neighborhood,[12] he was surprised to see Horowitz walking toward him. It turned out that Horowitz was coming to see him about his dream – which was one and the same.[10]

They had each envisioned an elderly man, his face shining with an otherworldly light, who had forcefully requested them to teach his Torah in Jerusalem. "My Torah has the power to bring the Divine Presence back from its exile," the man had said. Horowitz determined that the man in the dream was Rabbi Isaac Luria (known as the "Arizal"), the sixteenth-century mystic of Safed who was known to have regretted the fact that his Torah was not widely studied among Jerusalem's Ashkenazi population. At that time, the only place where the Arizal's kabbalah was studied was the Beit El Synagogue in Jerusalem, which had produced such great Sephardi kabbalists as Rabbi Shalom Sharabi ("the Rashash") and Rabbi Yedidiah Abulafia.[10]

On the spot, Auerbach and Horowitz decided to open a yeshiva for the study of the Arizal's kabbalah and share the responsibilities as joint roshei yeshiva.[10][13] The yeshiva opened shortly afterwards in the Old City of Jerusalem, with accommodations for a Talmud Torah, a yeshiva ketana, a yeshiva gedola, and a kollel for married students.[10]

Auerbach served as rosh yeshiva of Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva from 1906 until his death in 1954. When his father, the Admor of Chernowitz-Chmielnik, died, his father's Hasidim asked him to become their Rebbe. But Auerbach opted to stay on as rosh yeshiva of Shaar Hashamayim, leaving the position of Admor unfilled.[10]

Leadership of the yeshiva has remained in the Auerbach family up to the present day. After Auerbach's death, his son, Rabbi Eliezer Auerbach, served as rosh yeshiva for many years. After the latter's death, another of Rabbi Auerbach's sons, Rabbi Refoel Dovid Auerbach, assumed leadership. Today Shaar Hashamayim Yeshiva is headed by Rabbis Yaakov Meir Shechter and Gamliel Rabinowitz.[10]

Auerbach's eldest son, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, served as president of the yeshiva; after his death, his son, Rabbi Shmuel Auerbach, succeeded him. Rabbi Shlomo Zalman's nephew, Rabbi Yechezkel Schlaff of London, serves as yeshiva administrator.[10]

References

- Schwartz (1996), p. 34.

- Schwartz (1996), pp. 32–33.

- Schwartz (1996), p. 26.

- Sofer, D. "Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach zt"l". Yated Ne'eman (United States). Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- Lazewnik (2000), p. 48.

- Lazewnik (2000), p. 43.

- Lazewnik (2000), p. 29.

- Schwartz (1996), pp. 30–31.

- Lazewnik (2000), p. 40.

- Gefen, Rabbi Aryeh (20 September 2006). "A Century Since the Founding of Yeshivas Shaar HaShamayim, 5666-5766". Dei'ah VeDibur. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Lazewnik (2000), p. 36.

- Shwartz, Eliyahu Yekutiel (2005). "My Life's Story" (PDF). Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Memorial Committee. p. 32.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rossoff, Dovid (2005). קדושים אשר בארץ: קברי צדיקים בירושלים ובני ברק [The Holy Ones in the Earth: Graves of the Righteous in Jerusalem and Bnei Brak] (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Machon Otzar HaTorah. p. 425.

Sources

- Lazewnik, Libby (2000). Voice of Truth: The life and eloquence of Rabbi Sholom Schwadron, the unforgettable Maggid of Jerusalem. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Mesorah Publications. p. 29. ISBN 9781578195008.

- Schwartz, Rabbi Yoel (1996). The Man of Truth and Peace: Rabbenu Shlomo Zalman Auerbach zt"l. Kest-Lebovits Jewish Heritage and Roots Library.

Further reading

- Meir, Jonatan. "The Imagined Decline of Kabbalah: The Kabbalistic Yeshiva Sha'ar ha-Shamayim and Kabbalah in Jerusalem in the Beginning of the Twentieth Century" in Kabbalah and Modernity. Boaz Huss, Marco Pasi, and Kocku von Stuckrad, eds. Brill: Leiden & Boston, 2010, pp. 197–220.