Chaîne opératoire

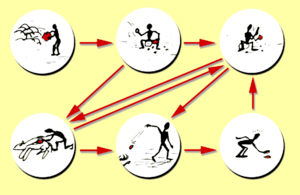

Chaîne opératoire (French for "operational chain" or "operational sequence") is a term used throughout anthropological discourse, but is most commonly used in archaeology and sociocultural anthropology. It functions as a methodological tool for analysing the technical processes and social acts involved in the step-by-step production, use, and eventual disposal of artifacts, such as lithic reduction (the making of stone tools) or pottery.[1][2][3] This concept of technology as the science of human activities was first proposed by French archaeologist, André Leroi-Gourhan, and later by the historian of science, André-Georges Haudricourt.[1][4] Both were students of Marcel Mauss who had earlier recognised that societies could be understood through its techniques by virtue of the fact that operational sequences are steps organised according to an internal logic specific to a society.[4][5]

The chaîne opératoire was born out of the need to explicitly describe the methodology of lithic analysis in archaeological scholarship. It allows archaeologists to reconstruct the techniques used and the chronological ordering of the different steps required to produce an artifact.[4] By understanding the processes and construction of tools, archaeologists can better determine the evolution of tool technology and the development of ancient cultures and lifestyles.[6] Artifact analysis has undergone several changes throughout its history, shifting from an orientation as a natural science of prehistoric humans to a social and cultural anthropology of the production techniques of prehistoric societies.[4] From this perspective, a chaîne opératoire can be understood as a social product, as it calls for an interdisciplinary approach to artifact analysis (the integration of associated disciplines: archaeology, sociocultural anthropology, biological anthropology, and anthropological linguistics), which offers a multidimensional view of a society, and demonstrates how chaînes opératoires cannot operate independently of the society that produces it.[3] Consequently, the study of the technique - or chaîne opératoire - enables one to better understand not only the society in which the technique originated, but also the social context, actions, and cognition that accompanied the production of an object.[4]

Criticism of chaîne opératoire

Critics of chaîne opératoire argue that it is subjective because it is based upon the analyst's personal experience and intuition.[7] They further claim that it is not a replicable or quantifiable approach to data collection. A second objection is that chaîne opératoire claims to be able to identify the intentions and goals of prehistoric knappers, including the "desired endproducts" of knapping sequences.[8] However, what archaeologists select from an assemblage as "end products" may not match what people in the past thought worthwhile to select for transport and subsequent use elsewhere in the landscape.[9] A third major problem with the chaîne opératoire approach is that there is severe inconsistency in the application of definitions by lithic analysts. For example, since the publication of Boëda's definition[10] of six nondisassociable criteria for Discoidal debitage, numerous variants have been proposed, and many authors have argued for the presence of Levallois concept even when those six criteria were not met.[11][12]

References

- Timothy Darvill (2002). "Chaîne opératoire, definition from Answers.com". Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology. Oxford University Press and Answers.com. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- Roger Grace (1997). "The 'chaîne opératoire' approach to lithic analysis". Stone Age Reference Collection. Institute of Archaeology, University of Oslo, Norway. Archived from the original on 2011-12-25. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- Gosselain, Oliver (1992). and Style.pdf "Technology and Style: Potters and Pottery Among Bafia of Cameroon" Check

|url=value (help) (PDF). Man. 27 (3): 559–586. doi:10.2307/2803929. JSTOR 2803929. - Soressi, Marie; Geneste, Jean-Michel (2011). "Special Issue: Reduction Sequence, Chaîne Opératoire, and Other Methods: The Epistemologies of Different Approaches to Lithic Analysis; The History and Efficacy of the Chaîne Opératoire Approach to Lithic Analysis: Studying Techniques to Reveal Past Societies in an Evolutionary Perspective". PaleoAnthropology. 2011: 336. doi:10.4207/PA.2011.ART63.

- Coupaye, Ludovic (2009). "Ways of Enchanting: Chaînes Opératoires and Yam Cultivation in Nyamikum Village, Maprik, Papua New Guinea". Journal of Material Culture. 14 (4): 440. doi:10.1177/1359183509345945.

- Forestier H, Zeitoun V, Winayalai C and Métais C 2013. The open-air site of Huai Hin (Northwestern Thailand): Chronological perspectives for the Hoabinhian. Comptes Rendus Palevol 12(1)

- Monnier, Gilliane F.; Missal, Kele (November 2014). "Another Mousterian Debate? Bordian facies, chaîne opératoire technocomplexes, and patterns of lithic variability in the western European Middle and Upper Pleistocene". Quaternary International. 350: 59–83. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.06.053.

- Bar‐Yosef, Ofer; Van Peer, Philip (February 2009). "The Chaîne Opératoire Approach in Middle Paleolithic Archaeology" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 50 (1): 103–131. doi:10.1086/592234.

- Turq, Alain; Roebroeks, Wil; Bourguignon, Laurence; Faivre, Jean-Philippe (November 2013). "The fragmented character of Middle Palaeolithic stone tool technology". Journal of Human Evolution. 65 (5): 641–655. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.07.014.

- Boëda, Eric (1993). "Le débitage Discoïde et le débitage Levallois récurrent centripète". Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française. 90 (6): 392–404. doi:10.3406/bspf.1993.9669.

- Draily, C. (2011). "La Grotte Walou à Trooz (Belgique): Fouilles de 1996 à 2004 L'Archéologie. Namur: Etudes et Documents". L'Archéologie. 22 (3).

- DiModica, K. (2010). Les productions lithiques du Paléolithique moyen de Belgique: variabilité des systèmes d'acquisition et des technologies en réponse à une mosaïque d'environnements contrastés (Doctoral dissertation). Liege: Département des Sciences Historiques, Université de Liege.