Ceremony (Silko novel)

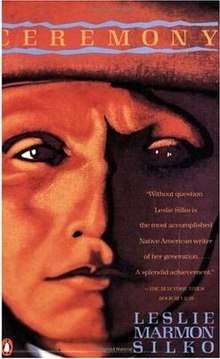

Ceremony is a novel by Native American writer Leslie Marmon Silko, first published by Penguin in March 1977. The title Ceremony is based upon the oral traditions and ceremonial practices of the Navajo and Pueblo people.

| |

| Author | Leslie Marmon Silko |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Lee Marmon (First Edition) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Published | March 1977 Penguin Books |

| Media type | Paperback |

| Pages | 262 |

| ISBN | 0-14-008683-8 |

| OCLC | 12554441 |

| Followed by | Storyteller (1981) |

Plot

Ceremony follows a half-Pueblo, half-white man named Tayo after his return from World War II. His white doctors say he is suffering from "battle fatigue," which would be called post-traumatic stress disorder today. In addition to Tayo's story in the present, the novel flashes back to his experiences before and during the war. A parallel story tells of a time when the Pueblo nation was threatened by a drought as punishment for listening to a practitioner of "witchery"; to redeem the people, Hummingbird and Green Bottle Fly must journey to the Fourth World to find Reed Woman.

Tayo is struggling with the death of his cousin Rocky during the Bataan Death March, and the loss of his uncle Josiah, who died on the Pueblo while Tayo was at war. After several years at a military hospital, Tayo is released by his doctors, who believe he will do better at home. While staying with his family, Tayo can barely get out of bed, and self-medicates with alcohol. His fellow veterans Harley, Leroy, Pinkie, and Emo drink with him, discussing their disappointment from fighting in a white man's war and having nothing to show for it. It is revealed that Tayo once stabbed Emo with a broken bottle because Emo was bragging about taking the teeth of a slain Japanese soldier.

Meanwhile, the Laguna Pueblo reservation is suffering from a drought, an event which mirrors the myth. Looking to help Tayo, his grandmother summons a medicine man named Ku'oosh. However, Ku'oosh's ceremony is ineffective against Tayo's battle fatigue because Ku'oosh can't understand modern warfare. He sends Tayo to another medicine man named Betonie, who incorporates elements of the modern world into his ceremonies. Betonie tells Tayo about the Destroyers who are bent on destabilizing the world, and says that Tayo must complete the ceremony to save the Pueblo people.

Believing that he bears responsibility for the drought, Tayo sets out to keep a promise he made to Josiah to round up Josiah's stolen cattle. While riding south after the cattle, he meets a woman named Ts'eh, whom he sleeps with for a night. He eventually finds the cattle on the property of a wealthy white rancher. Tayo cuts through the ranch fence, but is discovered by the ranch's employees. The tracks of a huge cougar -- heavily implied to be a form of Ts'eh -- distract them, and Tayo escapes. Ts'eh and her brother help Tayo trap the cattle in an arroyo so he can drive them back to the pueblo.

The next year, Tayo reunites with Ts'eh, and spends an idyllic time with her until Tayo's drinking buddies return for him. After a night of drinking, Tayo realizes he cannot complete the ceremony while drunk, and abandons the others after sabotaging their truck. Later that night, Emo tortures Harley near the site of the Trinity nuclear test, trying to lure Tayo out to settle their score. In contrast to their past confrontation, Tayo decides not to fight. A fight ensues among the other men that results in the deaths of Harley and Leroy.

Tayo goes back home to the pueblo and tells the elders he has completed the ceremony by recovering the cattle, abstaining from violence, and meeting a spirit woman in the form of Ts'eh. Meanwhile, in the mythic parallel story, Hummingbird and Green Bottle Fly find Reed Woman in the Fourth World. In each storyline, the act of ceremonial reunion brings an end to the drought, and the Pueblo are saved. Emo is banned from the reservation after killing Pinkie, and Tayo lives a content life tending to his herd of cattle.

Characters

- Tayo, World War II veteran of Laguna Pueblo and Anglo descent

- Betonie, mixed-blooded Navajo healer

- Ku'oosh, Laguna kiva priest

- Uncle Josiah, confidant to Tayo who died during World War II

- Ts'eh, a highly spiritual woman whom Tayo loves

- Rocky, Tayo's cousin; died during the Bataan Death March

- Harley, friend to Tayo and fellow World War II veteran

- Old Grandma, family matriarch and believer in customary pueblo religion

- Auntie, Rocky's mother who also raised Tayo; Catholic convert who rejects the Pueblo religion

- Laura, known primarily as "Little Sister"; Tayo's mother and sister to Auntie

- Uncle Robert, Auntie's husband

- Emo, Tayo's fellow veteran with a grudge against him

- Pinkie, veteran and follower of Emo

- The Night Swan, girlfriend of Uncle Josiah whom Tayo later sleeps with

- Ulibarri, cousin of the Night Swan from whom Josiah purchases the cattle

Timelines

Peter G. Beidler and Robert M. Nelson of University of Richmond argue that the novel is composed of six timelines:

- The main timeline

- Tayo and Rocky's boyhood

- Tayo and Rocky's early manhood

- Tayo and Rocky's enlistment and deployment in WWII

- Tayo's return to the pueblo

- The mythic action of Spider Woman, Hummingbird, Green Bottle Fly, and Reed Woman, as well as the witchery and the Destroyers

Main Timeline

- C. 1922: Tayo is born.

- 1941: Tayo and Rocky enlist and are sent overseas. Harley, Emo, and Leroy are at Wake Island. Josiah dies on the pueblo. Tayo and Rocky are taken prisoner

- April–May 1942: Rocky is wounded, and dies on Bataan Death March; Tayo curses the rain and the flies, and ends up in a POW camp. Drought begins in New Mexico

- July 16, 1945: Trinity Site Test in New Mexico, first atomic bomb test.

- 1945–1948: Tayo is in veterans hospital mental ward; Tayo is sent home and begins adventures in Dixie bar with Harley, Leroy, Pinkie and Emo.

- May 1948: Tayo is lying in bed, sick at his Auntie's house. Harley arrives on a burro and convinces him to go and get a beer. Ceremony with Ku'oosh fails.

- Late July 1948: Tayo says he is better, but the old men believe that he needs a stronger ceremony, so they refer him to Betonie. Tayo leaves for a while and meets Harley, Leroy and Helen Jean, who go as far away as San Fidel. He wakes up in the morning and vomits, and finally sees the horrible truth about his friends' drunkenness.

- Late September 1948: Tayo goes to Mt. Taylor on his ceremony, trying to retrieve the spotted cattle. He meets Ts'eh, sleeps with her, cuts the fence and retrieves the cattle from the white rancher, meets the hunter, and brings the cattle home.

- Winter 1948–1949 Tayo lives with Auntie, Grandma, and Robert before going back to the ranch to look after the cattle

- Summer 1949: Tayo meets Ts'eh, they pick flowers and herbs, Tayo gets a yellow bull to breed with his cattle, and Ts'eh warns him that "they" will be coming for him at the end of the summer.

- Late September 1949: During the fall equinox, Tayo gets drunk with Harley and Leroy before coming to his senses and disabling their truck. He and Emo have their final confrontation near Jackpile Uranium mine and Trinity Site, and opts not to stab Emo with the screwdriver, letting him kill Harley and Leroy. The next day, Tayo tells Ku'oosh and the elders in a kiva at old Laguna everything that he has seen.

Mythical Timeline

- Creation: Ts'its'tsi'nako (Thought Woman or Spider Woman) and her daughter/sisters Nau'ts'ity'i (Corn Woman) and I'cts'ity'i (Reed Woman) set life in motion

- Recovery/Transformation: The Keresan prayer for sunrise

- Departure: Corn Woman scolds Reed Woman for being lazy, and she departs; Drought begins

- Departure and Recovery: Pa'caya'nyi introduces Ck'o'yo medicine, and the People forget their obligation to Nau'ts'ity'i

Symbols and themes

Storytelling

In Ceremony, there are no conventional chapters and a part of the novel is written in prose, whereas other parts are written in a poetic form. The novel weaves together a number of different timelines and stories throughout. Apart from the function of storytelling words are very important for the Laguna oral tradition. The responsibility of humans is to tell stories, because words do not exist alone, they need a story. (229).[1] Betonie and Tayo's grandmother tell various stories and therefore fulfill this responsibility. The significance and the power of words are emphasized by Tayo cursing the rain with words and by the following appearance of the drought (230).[1] Based on the Spiderwoman one can also see how powerful words and thoughts are. The Spiderwoman is a mystical creature who set the world and whatever she says or thinks appears (Preface).[2] When she vocalizes her thoughts and by doing so names things, they become reality (230).[1] Through storytelling myths are handed down and they teach the history of the Laguna people and how they live (71).[3] They also connect the past with the present (71),[3] because myths are old and when they are being told, they become a part of the present.

Ceremony and healing

The purpose of ceremonies is the transformation of someone from one condition to another (71) [3] as in Tayo's case the transformation from diseased to healing. Ceremonies are ritual enactments of myths (71) [3] which incorporate the art of storytelling and the myths and rituals of the Native Americans (70).[3] They are important for Tayo's identity construction as one can see through his mental development after his experience with Betonie and the ceremony (144).[3]

In the novel “healing” means the recovery of the self and the return to the roots (45)[4] and one important part of the process of healing is rejecting witchery (54).[4] Tayo rejects witchery when he refuses to drink alcohol his friends offer him (144).[5] He does not only refuse to drink alcohol, he also distances himself from his old friends and a life full of violence. The search for the Laguna culture and its rituals also helps him to deal with turning away from witchery (54).[6] He respects the rituals of his culture by being open for the ceremonies which is another important aspect for his healing (54).[4] Tayo is being taught spirituality by Betonie, this way he internalizes the Laguna culture (133).[7] It is important that the Laguna community, e.g. his aunt, who tells Tayo to go to Betonie, helps Tayo with his healing, because that way Tayo can overcome the alienation he feels caused by him being half-breed. Betonie also helps Tayo to recover through ceremonies which relates Tayo's American identity to his Laguna identity and therefore combines his past with his present (150).[7] The fact that Tayo learns more about and experiences ceremonies is another important aspect which leads him to healing, because he learns about his culture.

The appreciation of the Laguna culture is essential for his healing. He still needs a spiritual ceremony after the white man's medicine, which indicates that he needs to experience his old and his new culture (53).[4] When Tayo covers the deer's dead body at the deer-hunting, which is a gesture performed out of respect, he shows that he initiated Laguna myths, because Laguna mythology connects all living creatures (48).[4] After the ceremony Tayo's dreams no longer haunt him, because he learns to deal with his past and he is able to link the American to the Laguna culture (151).[7] The cattle function as spirit guides, which leads him to healing (374),[8] because through them he learns to forgive himself for the drought (376).[8]

Native/Ethnic Identity

The identity of the protagonist Tayo is influenced by his ethnicity. Tayo is described as “half-breed” because, in contrast to his mother, who is a Native American woman, his father is white and does not belong to the Laguna community. His father left the family and Tayo and his mother were supported by his aunt and her husband. The Laguna community in which he has grown up segregates him and he experiences despair for not being fully Native American (71).[3] That he is not trained or educated in the Laguna way of life supports this fact (71).[3] Therefore, Tayo struggles between white and Native American culture and he feels like not belonging to any culture at all. The Laguna people believe that every place, object, landscape or animal relates to stories of their ancestors (2).[7] To develop this cultural identity it is important to take care of the land and the animals. By taking care of the cattle Tayo begins to take a more active and creative role in relations to nature and to his people which supports development of his cultural identity (248).[9] On top of that the cattle function as a symbol for being alienated and different, because they are a mix of different breeds, as well. This is described as positive because the “half-breed” cattle are, like Tayo, strong, robust, and can survive hard times. Therefore, they can be seen as a leitmotif for surviving (367).[8]

Moreover, the city of Gallup represents the struggle of American and Native identity. As being a former Native American city, which was built on Native American territory, Gallup changed into a city that relies on the “Indian” tourism industry. The white Americans suppress the real presence of Native Americans and push them to the borders of the city (491).[10] The Native Americans who lived in the city of Gallup and felt related to the land were pushed back to a specific zoning place under the bridge to divide them from the white civilization (265).[10] They use the former image of the city to attract tourists and make profit. Now only ethnically mixed outcasts live there (265).[10] As Tayo states: “I saw Navajos in torn jackets, standing outside the bar. There were Zunis and Hopis there, too, even a few Lagunas.” (98).[11]

Military Service and Trauma

Serving in the war as an American soldier also enhances Tayo's identity struggle. When he was in the war, he represented the United States, but by returning to his hometown he feels invisible as an American and drifts in time and space (132).[7] By laying down the uniform of an American soldier, Tayo, and also the other Native American veterans, are not recognized as Americans anymore. This is underlined by the funeral of Tayo's friends Harley and Leroy. Tayo and his friends struggle to shape their identity between two different sorts of signifying realms, one the "official" American identity (signified by the flag) and the other, that of the erased Native American (signified by the corpse) ( 490).[10] Furthermore, he has a trauma from war and feels responsible for the death of his cousin Rocky.

Development

Silko began early work on Ceremony while living in Ketchikan, Alaska, in 1973 after moving there with her children, Robert and Kazimir, from Chinle, Arizona. The family relocated so her then-husband John Silko could assume a position in the Ketchikan legal services office.

Silko held a contract with Viking Press to produce a collection of short stories or a novel under editor Richard Seaver. Having no interest in creating a novel, Silko began work on a short story set in the American Southwest revolving around the character Harley and the comical exploits of his alcoholism. During this early work, the character Tayo appeared as a minor character suffering from "battle fatigue" upon his return from World War II. The character fascinated Silko enough to remake the story with Tayo as the narrative's protagonist. The papers from this early work are held at the Yale University library.

In February 1974, Silko took a break from writing Ceremony to assume the role of a visiting writer at a middle school in Bethel, Alaska. It was during this time Silko penned the early work on her witchery poetry featured in Ceremony, wherein she asserts that all things European were created by the words of an anonymous Tribal witch. This writing plays a formidable role in the novel's theme of healing. An expanded version of this work is featured in Storyteller.

The poetic works found in Ceremony were inspired by the Laguna oral tradition and the work of poet James Wright, with whom Silko developed a friendship after they met at a writer's conference at Grand Valley State University in June 1974, and years of written correspondence. These letters would be featured in the work The Delicacy and Strength of Lace edited by Ann Wright, wife of James Wright, and published in November 1985 after the poet's death.

Silko completed the manuscript to Ceremony in July 1975 shortly before returning to New Mexico.

Reception

Ceremony has been well received by readers, and received significant attention from academics, scholars, and critics. It is widely taught in university courses, as part of American Indian studies, American studies, history, religious studies, and literature courses.[12]

Poet Simon J. Ortiz has lauded Ceremony as a "special and most complete example of affirmation and what it means in terms of Indian resistance."[13]

Denise Cummings, Critical Media & Cultural Studies professor at Rollins College, has described Ceremony as a novel which "immediately challenges readers with a new epistemological orientation while altering previously established understandings of the relationship between reader and text."[13]

Silko received the American Book Award for Ceremony in 1980.[14]

Further reading

- Akins, Adrienne (2012). ""Next Time, Just Remember the Story" Unlearning Empire in Silko's Ceremony". Studies in American Indian Literatures. 24 (1): 1–14. doi:10.5250/studamerindilite.24.1.0001. ISSN 1548-9590.

- Allen, Paula Gunn (1990). "Special Problems in Teaching Leslie Marmon Silko's" Ceremony"". American Indian Quarterly. 14 (4): 379–386. doi:10.2307/1184964. JSTOR 1184964.

- Chavkin, Allan Richard (2002). Leslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony: A Casebook. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195142839.

- Evasdaughter, Elizabeth N. (1988). "Leslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony: Healing Ethnic Hatred by Mixed-Breed Laughter". Melus. 15 (1): 83–95. doi:10.2307/467042. JSTOR 467042.

- Hokanson, Robert O'Brien (1997). "Crossing Cultural Boundaries with Leslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony" (PDF). Rethinking American Literature: 115–127.

- Olsen, Erica (2006). "Silko's CEREMONY". The Explicator. 64 (3): 184–186. doi:10.3200/expl.64.3.184-186.

- Ruppert, James (1993). "Dialogism and mediation in Leslie Silko's Ceremony". The Explicator. 51 (2): 129–134. doi:10.1080/00144940.1993.9937996.

- Staòková, Hana. "the Role of Women in Leslie marmon silko's novels" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Swan, Edith (1988). "Healing via the Sunwise Cycle in Silko's "Ceremony"". American Indian Quarterly. 12 (4): 313–328. doi:10.2307/1184404. JSTOR 1184404.

- Zamir, Shamoon (1993). "Literature in a 'National Sacrifice Area': Leslie Silko's Ceremony". New Voices in Native American Literary Criticism: 396–415.

References

- Swan, Edith (1988). "Laguna Symbolic Geography and Silko's "Ceremony"". American Indian Quarterly. 12 (3): 229–249. doi:10.2307/1184497. JSTOR 1184497.

- Silko, Leslie Marmon (1977). Ceremony. New York: Penguin. pp. Preface. ISBN 978-01400-86836.

- Gilderhus, Nancy (1994). "The Art of Storytelling in Leslie Marmon Silko's 'Ceremony'". The English Journal. 83 (2): 70. doi:10.2307/821160. JSTOR 821160.

- Farouk Fouad, Jehan, Alwakeel, Saeed (2013). "Representations of the Desert in Silko's "Ceremony" and Al-Koni's "The Bleeding of the Stone"". Journal of Comparative Poetics (33): 36–62.

- Silko, Leslie Marmon (1977). Ceremony. New York: Penguin. p. 144. ISBN 978-01400-86836.

- Flores, Toni (1989). "Claiming and Making: Ethnicity, Gender, and the Common Sense in Leslie Marmon Silko's 'Ceremony' and Zora Neale Hurston's 'Their Eyes Were Watching God'". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 10 (3): 52–58. doi:10.2307/3346441. JSTOR 3346441.

- Teuton, Sean Kicummah (2008). Red Land, Red Power: Grounding Knowledge in the American Indian Novel. Duke University Press. pp. 121–155.

- Blumenthal, Susan (1990). "Spotted Cattle and Deer: Spirit Guides and Symbols of Endurance and Healing in 'Ceremony'". American Indian Quarterly. 14 (4): 367–377. doi:10.2307/1184963. JSTOR 1184963.

- Holm, Sharon (2008). "The Lie of the Land: Native Sovereignty, Indian Literary Nationalism and Early Indigenism in Leslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony". The American Indian Quarterly. 32 (3): 243–274. doi:10.1353/aiq.0.0006.

- Piper, Karen (1997). "Police Zones: Territory and Identity in Leslie Marmon Silko's 'Ceremony'". American Indian Quarterly. 21 (3): 483–497. doi:10.2307/1185519. JSTOR 1185519.

- Silko, Leslie Marmon (1977). Ceremony. New York: Pinguin. p. 98. ISBN 978-01400-86836.

- Chavkin, Allan; Chavkin, Nancy Feyl (2007). "The Origins of Leslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony". The Yale University Library Gazette. 82 (1/2): 23–30. ISSN 0044-0175. JSTOR 40859362.

- Cummings, Denise K. (2000). ""Settling" History: Understanding Leslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony, Storyteller, Almanac of the Dead, and Gardens in the Dunes". Studies in American Indian Literatures. 12 (4): 65–90. ISSN 0730-3238. JSTOR 20736989.

- "American Book Awards | Before Columbus Foundation". Retrieved 2020-06-04.