Ceramide synthase 2

Ceramide synthase 2, also known as LAG1 longevity assurance homolog 2 or Tumor metastasis-suppressor gene 1 protein is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the CERS2 gene.

Ceramide synthase 2 is a ceramide synthase that catalyses the synthesis of very long acyl chain ceramides, including C20 and C26 ceramides. It is the most ubiquitously expressed of all CerS and has the broadest distribution in the human body.[5]

CerS2 was first identified in 2001.[6] It contains the conserved TLC domain and Hox-like domain common to almost all CerS.[7]

Distribution

CerS2 mRNA (TRH3) has been found in most tissues and it is strongly expressed in liver, intestine and brain.[8] CerS2 is much more widely distributed than Ceramide synthase 1 (CerS1) and is found in at least 12 tissues in the human body, with high expression in the kidney and liver, and moderate expression in the brain and other organs. In the mouse brain, CerS2 is mainly expressed white matter tracts, specifically in oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells.[7][9]

Function

Expression of CerS2 is transiently increased during periods of active myelination, suggesting that it is important for the synthesis of myelin sphingolipids.[9] The lack of CerS2, as shown in knockout mice, induces the autophagy and activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR).[7] These mice showed no decrease in overall ceramide level, but levels of sphinganine were elevated. They also developed severe liver disease, but there was no observable change in the kidneys.[10]

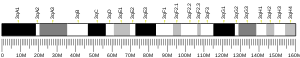

The CerS2 gene is compact in size and is located in a chromosomal region that is replicated early in the cell cycle.[7] CerS2 activity is regulated by sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) via two sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-like residues on CerS2 that operate independently.[7]

Pathological significance

CerS2 levels are significantly elevated in breast cancer tissue compared to normal tissue, along with increased levels of ceramide synthase 6 (CerS6).[7]

CerS2 was also implicated in the control of body weight. The administration of leptin to rats induced a decrease in CerS2 was observed in white adipose tissue.[7]

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000143418 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000015714 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Stiban J, Tidhar R, Futerman AH (2010). "Ceramide synthases: roles in cell physiology and signaling". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 688: 60–71. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-6741-1_4. PMID 20919646.

- Pan H, Qin WX, Huo KK, et al. (September 2001). "Cloning, mapping, and characterization of a human homologue of the yeast longevity assurance gene LAG1". Genomics. 77 (1–2): 58–64. doi:10.1006/geno.2001.6614. PMID 11543633.

- Levy M, Futerman AH (May 2010). "Mammalian ceramide synthases". IUBMB Life. 62 (5): 347–56. doi:10.1002/iub.319. PMC 2858252. PMID 20222015.

- Riebeling C, Allegood JC, Wang E, Merrill AH Jr, Futerman AH (Oct 2003). "Two mammalian longevity assurance gene (LAG1) family members, trh1 and trh4, regulate dihydroceramide synthesis using different fatty acyl-CoA donors". J Biol Chem. 278 (44): 43452–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M307104200. PMID 12912983.

- Becker I, Wang-Eckhardt L, Yaghootfam A, Gieselmann V, Eckhardt M (February 2008). "Differential expression of (dihydro)ceramide synthases in mouse brain: oligodendrocyte-specific expression of CerS2/Lass2". Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 129 (2): 233–41. doi:10.1007/s00418-007-0344-0. PMID 17901973.

- Pewzner-Jung Y, Brenner O, Braun S, Laviad EL, Ben-Dor S, Feldmesser E, Horn-Saban S, Amann-Zalcenstein D, Raanan C, Berkutzki T, Erez-Roman R, Ben-David O, Levy M, Holzman D, Park H, Nyska A, Merrill AH, Futerman AH (April 2010). "A critical role for ceramide synthase 2 in liver homeostasis: II. insights into molecular changes leading to hepatopathy". J. Biol. Chem. 285 (14): 10911–23. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.077610. PMC 2856297. PMID 20110366.

Further reading

- Rual JF, Venkatesan K, Hao T, et al. (2005). "Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network". Nature. 437 (7062): 1173–8. doi:10.1038/nature04209. PMID 16189514.

- Lewandrowski U, Moebius J, Walter U, Sickmann A (2006). "Elucidation of N-glycosylation sites on human platelet proteins: a glycoproteomic approach". Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 5 (2): 226–33. doi:10.1074/mcp.M500324-MCP200. PMID 16263699.

- Oh JH, Yang JO, Hahn Y, et al. (2006). "Transcriptome analysis of human gastric cancer". Mamm. Genome. 16 (12): 942–54. doi:10.1007/s00335-005-0075-2. PMID 16341674.

- Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, et al. (2006). "Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks". Cell. 127 (3): 635–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. PMID 17081983.

- Ewing RM, Chu P, Elisma F, et al. (2007). "Large-scale mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry". Mol. Syst. Biol. 3 (1): 89. doi:10.1038/msb4100134. PMC 1847948. PMID 17353931.