Catholicisation

Catholicisation refers mainly to the conversion of adherents of other religions into Catholicism, and the system of expanding Catholic influence in politics. Catholicisation was a policy of the Holy See through the Papal States, Holy Roman Empire, Habsburg Monarchy, etc. Sometimes this process is referred to as re-Catholicization although in many cases Catholicized people had never been Catholics before.[1]

The term is also used for the communion of Eastern Christian churches into the Roman Catholic Church; the Eastern Catholic Churches that follow the Byzantine, Alexandrian, Armenian, East Syrian, and West Syrian Rites, as opposed to the Roman Catholic Latin Rite.

Catholic doctrine

Propaganda

The Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (Latin: Congregatio pro Gentium Evangelizatione), formerly Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Latin: Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide) is the congregation of the Roman Curia responsible for missionary work and related activities.

In 1439 in Florence, the Declaration of Union was adopted, according to which "the Roman Church firmly believes that nobody, who does not belong to the Catholic Church, not only unbelievers, but Judeans (Jews), nor heretics, nor schismatics, cannot enter the kingdom of heaven, but all will go to the eternal fire, which is saved for devils and their angels, if they not before death turn to that church".[2] The Council of Trent (1545–63) had the mission to gain, apart from "stray" Protestants, also the numerous "schismatics" in southeastern Europe.[2]

Catholicisation and Uniatism

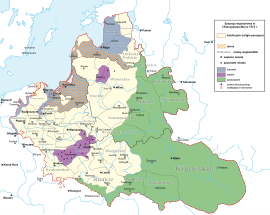

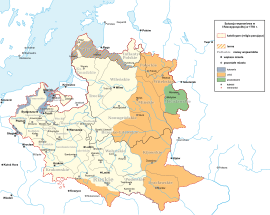

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

During the period from the 16th up to the 18the century, in eastern regions of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Kingdom of Hungary several successive campaigns of Catholicization were undertaken in order to convert local Eastern Orthodox Christians into Catholicism.[3][4][5]

Serbs

Since the 15th century Bosnian Franciscans were allowed to propagate their religious doctrine and work on gaining adherents.[2] The Council of Trent (1545–63) had the mission to gain both Protestants, and Orthodox Christians in southeastern Europe.[2] The Serbian Orthodox Church became targeted, the strongest pressure during the term of Pope Clement VIII (1592–1605), who used the difficult position of the Orthodox in the Ottoman Empire and conditioned the Serbian Patriarch to Uniatize in return for support against the Turks.[2]

Serbian Orthodox Christians and Bogomils were targeted for Catholicisation by clergy from Republic of Ragusa.[6]

Since the many migrations of Serbs into the Habsburg Monarchy beginning in the 16th century, there were efforts to Catholicize the community. The Orthodox Eparchy of Marča became the Catholic Eparchy of Križevci after waves of Uniatization in the 17th and 18th centuries.[7] Notable individuals active in the Catholicisation of Serbs in the 17th century include Martin Dobrović, Benedikt Vinković, Petar Petretić, Rafael Levaković, Ivan Paskvali and Juraj Parčić.[7][8][9] Catholic bishops Vinković and Petretić wrote numerous inaccurate texts meant to incite hatred against Serbs and Orthodox Christians, some of which included advice on how to Catholicize the Serbs.[10]

During World War II, the Axis Ustashe led the campaign of Genocide of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia. An estimated 300,000 were converted to Catholicism, most temporarily.

Albanians

Christianity in Albania was under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome until the 8th century. Then, dioceses in Albania were transferred to the patriarchate of Constantinople. In 1054 after the schism, the north became identified with the Roman Catholic Church.[11] Since that time all churches north of the Shkumbin river were Catholic and under the jurisdiction of the Pope.[12] Various reasons have been put forward for the spread of Catholicism among northern Albanians. Traditional affiliation with the Latin rite and Catholic missions in central Albania in the 12th century fortified the Catholic Church against Orthodoxy, while local leaders found an ally in Catholicism against Slavic Orthodox states.[13] [12][14]

Recatholicisation during Counter-Reformation

See also

Christianization by the Papacy

References

- Peter Hamish Wilson (2009). The Thirty Years War: Europe's Tragedy. Harvard University Press. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-674-03634-5.

- Vuković 2004, p. 424.

- Litwin 1987, p. 57–83.

- Tóth 2002, p. 587-606.

- Kornél 2011, p. 33-56.

- Irena Ipšić, 2013, Vlasništvo nad nekretninama crkvenih i samostanskih ustanova na orebićkome području u 19. stoljeću,https://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=155415 #page=235

- Kašić, Dušan Lj (1967). Srbi i pravoslavlje u Slavoniji i sjevernoj Hrvatskoj. Savez udruženja pravosl. sveštenstva SR Hrvatske. p. 49.

- Kolarić, Juraj (2002). Povijest kršćanstva u Hrvata: Katolička crkva. Hrvatski studiji Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. p. 77. ISBN 978-953-6682-45-4.

- Dimitrijević, Vladimir (2002). Pravoslavna crkva i rimokatolicizam: (od dogmatike do asketike). LIO. p. 337.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gavrilović, Slavko (1993). Iz istorije Srba u Hrvatskoj, Slavoniji i Ugarskoj: XV-XIX vek. Filip Višnjić. p. 30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (1989). Religion and Nationalism in Soviet and East European Politics. Duke University Press. p. 381. ISBN 0-8223-0891-6.

Albanian Christianity lay within the orbit of the bishop of Rome from the first century to the eighth. But in the eighth century Albanian Christians were transferred to the jurisdiction of the patriarch of Constantinople. With the schism of 1054, however, Albania was divided between a Catholic north and an Orthodox south. [..] Prior to the Turkish conquest, the ghegs (the chief tribal group in northern Albania) had found in Roman Catholicism a means of resisting the Slavs, and though Albanian Orthodoxy remained important among the tosks (the chief tribal group in southern Albania)

- Murzaku, Ines (2015). Monasticism in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Republics. Routledge. p. 352. ISBN 1317391047. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

The Albanian church north of Shkumbin River was entirely Latin and under the pope's jurisdiction. During the twelfth century, the Catholic church in Albania intensified efforts to strengthen its position in middle and southern Albania. The Catholic Church was organized in 20 dioceses.

- Lala, Etleva (2008), Regnum Albaniae, the Papal Curia, and the Western Visions of a Borderline Nobility (PDF), Central European University, Department of Medieval Studies, p. 1

- Leften Stavros Stavrianos (January 2000). The Balkans Since 1453. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 498. ISBN 978-1-85065-551-0.

Religious differences also existed before the coming of the Turks. Originally, all Albanians had belonged to the Eastern Orthodox Church... Then the Ghegs in the North adopted in order to better resist the pressure of Orthodox Serbs.

Sources

- Books

- Caffiero, Marina; Cochrane, Lydia G. (2012). Forced Baptisms: Histories of Jews, Christians, and Converts in Papal Rome. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25451-0.

- Ó hAnnracháin, Tadhg (2015). Catholic Europe, 1592-1648: Centre and Peripheries. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927272-3.

- Paris, Edmond (1988). Convert-- or die!: Catholic persecution in Yugoslavia during World War II. Chick Publications.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skinner, Barbara (2009). The Western Front of the Eastern Church: Uniate and Orthodox Conflict in 18th-century Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-87580-407-1.

- Journals

- Atlagić, M. (2008). "Katoličenje Srba na Kosovu i Metohiji u XVII vijeku" (PDF). Baština (25): 137–147.

- Bourdeaux, M., 1974. The Uniate churches in Czechoslovakia. Religion in Communist Lands, 2(2), pp. 4–6.

- Forster, M.R., The Thirty Years' War and the Failure of Catholicization. The Counter-Reformation: The Essential Readings, pp. 163–97.

- Ionescu, D., 1991. Roumania: The Orthodox-Uniate Conflict. Report on Eastern Europe, 2(31).

- Kornél, Nagy (2011). "The Catholicization of Transylvanian Armenians (1685-1715): Integrative or Disintegrative Model?". Integrating Minorities: Traditional Communities and Modernization. Cluj-Napoca: Editura ISPMN. pp. 33–56. ISBN 9786069274491.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Litwin, Henryk (1987). "Catholicization among the Ruthenian Nobility and Assimilation Processes' in the Ukraine during the Years 1569-1648" (PDF). Acta Poloniae Historica. 55: 57–83. ISSN 0001-6829.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sadkowski, K. (1998). "From Ethnic Borderland to Catholic Fatherland: The Church, Christian Orthodox, and State Administration in the Chelm Region, 1918-1939". Slavic Review. 57 (4): 813–839. doi:10.2307/2501048. JSTOR 2501048.

- Tóth, István György (2002). "Počiatky rekatolizácie na východnom Slovensku (The Beginning of re-Catholicization in Eastern Slovakia)". Historický časopis. 50 (4): 587–606.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vuković, Slobodan V. (2004). "Uloga Vatikana u razbijanju Jugoslavije". Sociološki Pregled. 38 (3): 423–443. doi:10.5937/socpreg0403423V.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conference papers

- Cuming, G. J., ed. (2008). The Mission of the Church and the Propagation of the Faith: Papers read at the Seventh Summer Meeting and the Eighth Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History Society. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-10179-0.