Casement Report

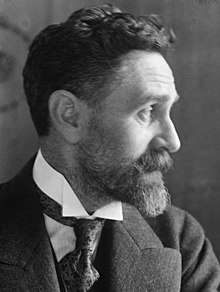

The Casement Report was a 1904 document written by Roger Casement (1864–1916)—a diplomat and Irish independence fighter—detailing abuses in the Congo Free State which was under the private ownership of King Leopold II of Belgium. This report was instrumental in Leopold finally relinquishing his private holdings in Africa. Leopold had had ownership of the Congolese state since 1885, granted to him by the Berlin Conference, in which he exploited its natural resources (mostly rubber) for his own private wealth.

Prelude: The Stokes Affair

Through intercepted letters, Captain Hubert-Joseph Lothaire, the commander of the Congo Free State forces in the Ituri-campaign, learned that Charles Stokes (born in Dublin) was on his way from German East Africa to sell weapons to the Zanzibari slavers in the eastern Congo region. Stokes was arrested and taken to Captain Lothaire in Lindi, who immediately formed a Drumhead court-martial. Stokes was found guilty of selling guns, gunpowder and detonators to the Congo Free State's Afro-Arab enemies. On 14 January 1895 he was sentenced to death and was hanged the next day (hoisted on a tree).

To Lothaire, Charles Stokes was no more than a criminal whose hanging was fully justified. Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister at the time, commented that if Stokes was in league with Arab slave-trading, then ‘he deserved hanging’. Sir John Kirk, for years the British Consul in Zanzibar, remarked that “he was no loss to us, although he was an honest man.” The news of Stokes’ execution was received with indifference by the British Foreign Office. When the German ambassador asked Sir Thomas H. Sanderson, the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, whether the British government planned to take any steps regarding the execution of this “well-known character”, Sanderson wrote: “I do not quite understand why the Germans are pressing us.”

In August 1895, the attention of the British press was drawn to this case by Lionel Decle, a journalist for the Pall Mall Gazette. The press began to report on these events in great detail, The Daily News emphasized 'bloodthirsty precipitation' , The Times a 'painful and disgraceful death', The Liverpool Daily Post 'horrified amazement through the British race', The Daily Telegraph 'death like a dog', adding 'Have we all been wrong in believing that the most audacious foreigner – not to speak of any savage chief – would think once, twice and even trice, before he laid hands on a subject of Queen Victoria'.[1]

As a result, the case became an international incident, better known as the Stokes Affair. Together, Britain and Germany pressured the Congo Free State to put Lothaire on trial, which they eventually did, a first trial was held in the city of Boma. The Free State paid compensation to the British (150,000 francs) and Germans (100,000 francs) and made it impossible by decree to impose martial law or death sentences on European citizens. Stokes's body was returned to his family.

Lothaire was acquitted twice, first in April 1896 by a tribunal in Boma. In August 1896, the appeal was confirmed in Brussels by the Supreme Court of Congo, paving the way for the rehabilitation of Lothaire.

The Stokes Affair mobilized British public opinion against the Congo Free State. It also damaged the reputation of King Leopold II of Belgium as a benevolent despot, which he had cultivated with so much effort. The case helped encourage the foundation of the Congo Reform Association – by Roger Casement – which on its turn put pressure on the Belgian government, which helped lead to the annexation of the Congo Free State by the Belgian state in 1908.[2]

Publicity 1895–1903

For many years prior to the Casement Report there were reports from the Congo alleging widespread abuses and exploitation of the native population. In 1895, the situation was reported to Dr Henry Grattan Guinness (1861–1915), a missionary doctor. He had established the Congo-Balolo Mission in 1889, and was promised action by King Leopold later in 1895, but nothing changed. H. R. Fox-Bourne of the Aborigines' Protection Society had published Civilisation in Congoland in 1903, and the journalist E. D. Morel also wrote several articles about the Leopoldian government's behaviour in the Congo Free State.

On 20 May 1903 a motion by the Liberal Herbert Samuel was debated in the British House of Commons, resulting in this resolution:

... That the Government of the Congo Free State having, at its inception, guaranteed to the Powers that its Native subjects should be governed with humanity, and that no trading monopoly or privilege should be permitted within its dominions, this House requests His Majesty's Government to confer with the other Powers, signatories of the Berlin General Act by virtue of which the Congo Free State exists, in order that measures may be adopted to abate the evils prevalent in that State.[3]

Subsequently, the British consul at Boma in the Congo, the Irishman Roger Casement was instructed by Balfour's government to investigate. His report was published in 1904, confirmed Morel's accusations, and had a considerable impact on public opinion.

Casement met and became friends with Morel just before the publication of his report in 1904 and realized that he had found the ally he had sought. Casement convinced Morel to establish an organization for dealing specifically with the Congo question. With Casement's and Dr. Guinness's assistance, he set up and ran the Congo Reform Association, which worked to end Leopold's control of the Congo Free State. Branches of the association were established as far away as the United States.

The Casement Report

The Casement Report comprises forty pages of the Parliamentary Papers, to which is appended another twenty pages of individual statements gathered by Casement as Consul, including several detailing grim tales of killings, mutilations, kidnappings and cruel beatings of the native population by soldiers of the Congo Administration of King Leopold. Copies of the Report were sent by the British government to the Belgian government as well as to nations who were signatories to the Berlin Agreement in 1885, under which much of Africa had been partitioned. The British Parliament demanded a meeting of the fourteen signatory powers to review the 1885 Berlin Agreement.[4]

While the Report was issued as a Command paper in 1904, and was laid before the Houses of Parliament, the original was not published in full until 1985, in an annotated book by two Belgian professors of the history of colonialism.[5]

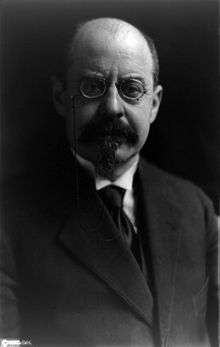

The Belgian Parliament, pushed by socialist political leader and statesman Emile Vandervelde and other critics of the King's Congolese policy, forced a reluctant Leopold II to set up an independent commission of enquiry. Its findings confirmed Casement's report in every detail. This led to the arrest and punishment of officials who had been responsible for murders during a rubber-collection expedition in 1903 (including one Belgian national who was given a five-year sentence for causing the shooting of at least 122 Congolese natives).

Dissolution of the Congo Reform Association

Despite these findings, Leopold managed to retain personal control of the Congo until 1908, when the Parliament of Belgium annexed the Congo Free State and took over its administration as the Belgian Congo. However the final push came from Leopold's successor King Albert I, and in 1912 the Congo Reform Association had the satisfaction of dissolving itself.

Other diplomatic manoeuvres by Roger Casement

Hindu-German Conspiracy

During World War I, Casement is known to have been involved in the "Hindu–German Conspiracy", a German-backed plan by Hindu nationalists to win their independence from the British Raj (formerly British India), recommending Joseph McGarrity to Franz von Papen as an intermediary. This Irish collaboration with Indian revolutionaries resulted in some of the early but failed efforts to smuggle arms into India, including a 1908 attempt on board a ship called the SS Moraitis which sailed from New York for the Persian Gulf before it was searched at Smyrna.[6] The Irish community later provided valuable intelligence, logistics, communication, media, and legal support to the German, Indian, and Irish conspirators. Those involved in this liaison, and later involved in the plot, included major Irish republicans and Irish-American nationalists like John Devoy, Joseph McGarrity, Roger Casement, Éamon de Valera, Father Peter Yorke and Larry de Lacey. These pre-war contacts effectively set up a network which the German foreign office tapped into as WWI began in Europe.[7] The Indian nationalists may also have followed Casement's strategy of trying to recruit prisoners of war to fight for Indian independence.

Anglo-Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company

In 1906 Casement was on his way to Brazil, where he became consul for the foreign office in Santos, then he was transferred to Pará,[8] and lastly he was promoted to consul-general in Rio de Janeiro.[9] He was attached as a consular representative to a commission investigating rubber slavery by the Anglo-Peruvian Amazon Rubber Co, which had been registered in Britain in 1908 and had a British board of directors and numerous stockholders. In September 1909, a journalist named Sidney Paternoster, wrote in Truth, a British magazine, of abuses against PAC workers and competing Colombians in the disputed region of the Peruvian Amazon.

Casement travelled to the Putumayo District, where the rubber was harvested deep in the Amazon Basin, and explored the treatment of the local indigenous peoples in Peru.[10] The isolated area was outside the reach of the national government and near the border with Colombia—which played an important role at that time, with the construction of the Panama Canal[11]—, Colombia periodically made incursions in competition for the rubber. For years, the indigenous peoples had been forced into unpaid labour by field staff of the Anglo-Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company, who exerted absolute power over them and subjected them to near starvation, severe physical abuse, rape of women and girls by the managers and overseers, branding and casual murder. Casement found conditions more inhumane than those in the Congo. He interviewed both the Putumayo and men who had abused them, including three Barbadians who had also suffered from conditions of the company. When the report was published, there was public outrage in Britain over the abuses.

Collaboration with the German Empire in WWI

In August 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, Casement and John Devoy arranged a meeting in New York with the western hemisphere's top-ranking German diplomat, Count Bernstorff, to propose a mutually beneficial plan: if Germany would sell guns to the Irish revolutionaries and provide military leaders, the Irish would revolt against England, diverting troops and attention from the war with Germany.[12]

In 1916, the British had intercepted German communications coming from Washington and suspected that there was going to be an attempt to land arms shipments on Irish shores, although they were not aware of the precise location. The arms ship SS Libau, masqueraded as a merchant ship, under Captain Karl Spindler, was apprehended by HMS Bluebell on the late afternoon of Good Friday.

In the early hours of 21 April 1916, three days before the Easter Rising began, the German submarine SM U-19 put Casement ashore at Banna Strand in Tralee Bay, County Kerry. Casement was suffering from a recurrence of malaria that had plagued him since his days in the Congo Free State, and too weak to travel, he was discovered at McKenna's Fort in Rahoneen, Ardfert, and arrested on charges of treason.[13]

A group of Irish American congressmen with the help of Joseph Tumulty (the President's personal and Irish-catholic secretary) presented a petition to Woodrow Wilson (of Scots-Irish descent) with the request to lean in on the Casement trial. Wilson was in the middle of his re-election campaign and was counting on the Irish American vote. The British hoping for American intervention in the war, could have hardly ignored a plea from Wilson. On 2 May 1916, Wilson wrote Tumulty: “We have no choice in a matter of this sort. It is absolutely necessary to say that I could take no action of any kind regarding it.”[14][15][16]

On 3 August 1916 Casement was hanged for treason, sabotage, and espionage against the British Crown on the basis of collaboration with the German Empire.

References

- Roger Louis, W. (1965). "The Stokes Affair and the Origins of the Anti-Congo Campaign, 1895–1896". Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire. 43: 572–584.

- Roger Louis, W. (1965). "The Stokes Affair and the Origins of the Anti-Congo Campaign, 1895–1896". Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire. 43: 572–584.

- Commons debate of 20 May 1903; (downloaded 23 Nov 2016)

- Foreign Office Blue Books, 1904 Cd. 1933

- Vellut J-L, and Vangroenweghe D.; Le Rapport Casement (Enquêtes et documents d'histoire africaine) Université Catholique de Louvain: Centre d'Histoire de l'Afrique (1985). Pp. xxviii + 174.

- Popplewell 1995, p. 148

- Plowman, Matthew Erin. "Irish Republicans and the Indo-German Conspiracy of World War I", New Hibernia Review 7.3 (2003), pp. 81–105.

- Brian Inglis, "Roger Casement" 1973, pp. 157–65

- See Roger Casement in: "Rubber, the Amazon and the Atlantic World 1884–1916" (Humanitas)

- Casement’s journal maintained during his 1910 investigation was published as The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement (London: Anaconda Editions, 1997). A companion volume of documents relevant to 1911 and his return to the Amazon was published as Angus Mitchell (ed.), Sir Roger Casement’s Heart of Darkness: The 1911 Documents (Irish Manuscripts Commission, 2003)

- Jane M. Rausch (2014). Colombia’s Neutrality during 1914–1918: An Overlooked Dimension of World War I. University of Massachusetts Amherst, USA. Iberoamericana, XIV, 53. pp. 103–115.

- Casement's diaries kept in Germany, containing his speaking openly of his treason, have been edited and published by Angus Mitchell (ed.), One Bold Deed of Open Treason: The Berlin Diary of Roger Casement 1914–1916 (Dublin: Merrion Press, 2016).

- Thomson, Sir Basil (2015). Odd People: Hunting Spies in the First World War (original title: Queer People). London, UK: Biteback Publishing. pp. e-book location 1161. ISBN 9781849548625. Sir Basil Thomson headed Scotland Yard's Criminal Investigation Division during WWI.

- Angus Mitchell (2003). Casement. London: Haus Publishing. p.150. ISBN 1-904341-41-1

- Terry Golway (1999). Irish Rebel: John Devoy and America's Fight for Ireland's Freedom. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-19903-1

- Robert Schmuhl (2016). Ireland's Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising. NY: Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- British Parliamentary Papers, LXII. (1904, Cd. 1933).

- Casement Report (1904).

- Dudgeon, Jeffrey (2002 and 2016). Roger Casement: The Black Diaries with a Study of His Background, Sexuality and Irish Political Life. Belfast. ISBN 0-9539287-2-1. Includes 1903 diary.

- Gondola, Ch. Didier (2002). The History of Congo. Greenwood Press: Westport, CT.

- Ó Síocháin, Séamas and Michael O’Sullivan, eds. (2004). The Eyes of Another Race: Roger Casement's Congo Report and 1903 Diary. University College Dublin Press. ISBN 1-900621-99-1.

- Ó Síocháin, Séamas (2008). Roger Casement: Imperialist, Rebel, Revolutionary. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

- Pierre-Luc Plasman (Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium) and Catherine Thewissen (Université catholique de Louvain), The Three Lives of the Casement Report: Its Impact on Official Reactions and Popular Opinion in Belgium, 1 April 2016, Breac: A Digital Journal of Irish Studies, Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies University of Notre Dame. http://breac.nd.edu/articles/the-three-lives-of-the-casement-report-its-impact-on-official-reactions-and-popular-opinion-in-belgium/

- Casements Kongo dagboek, één van de zogenoemde Black Diaries, was geen vervalsing, Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis (Revue belge d'histoire contemporaine), 2002.