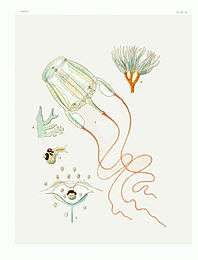

Carybdea marsupialis

Carybdea marsupialis, the sea wasp, is a venomous species of cnidarian, in the small family Carybdeidae within the class Cubozoa.

| Carybdea marsupialis | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Cubozoa |

| Order: | Carybdeida |

| Family: | Carybdeidae |

| Genus: | Carybdea |

| Species: | C. marsupialis |

| Binomial name | |

| Carybdea marsupialis | |

Description

Carybdea marsupialis is a small transparent jellyfish with a box-shaped bell[2] about 3 cm (1 in) across, at the four lower corners of which are four elongated tentacles up to 30 cm (12 in) long. The bell has a number of small white or yellowish warts with stinging cells, and near the margin, equidistant from the tentacles, are four rhopalia (sensory structures with ocelli). This species can be distinguished from other similar species by the red banding on the tentacles.[3][4]

Distribution

Carybdea marsupialis was once considered a widespread species found in warm oceans around the world. Taxonomic reviews have shown that most of these are other species in the genus Carybdea, with the true C. marsupialis essentially restricted to the Mediterranean Sea.[5] It is the only box jellyfish in this sea.[6] It is pelagic and is present in the upper few metres of the sea.[4]

Biology

Carybdea marsupialis is a predator and feeds on invertebrates and even small fish which it captures with the nematocysts (stinging cells) in its tentacles, often in shallow waters. It swims by making rapid contractions of the bell and can move at a speed of between 3 to 6 m (10 to 20 ft) per minute.[7] Like other species in its genus it has comparatively sophisticated eyes with lenses. With their help it can detect obstacles such as posts or a ship's rudder and avoid them. It often occurs in small groups. The sting is venomous to humans but some swimmers do not notice any painful sensation.[4] In severe cases, the symptoms can be systemic, including pain at the sting site and elsewhere, paresthesia, hyperesthesia and skin lesions, and may take a few months to fully disappear.[6] Although it is far less dangerous than some box jellyfish species from other parts of the world, it is considered the second-most important stinging jellyfish in the Mediterranean (Pelagia noctiluca being the most important).[8]

The life history of this box jellyfish is complex. The sexes are separate and sexual reproduction takes place with the emission of gametes into the open water. After fertilisation, a planula larva forms which later develops into a cubopolyp with a few tentacles.[4] This can reproduce asexually by budding, the buds soon becoming detached. At first they creep across the substrate with the tentacular region leading. During this mobile stage, pieces may become detached or the cubopolyp may split transversely; these fragments regenerate their missing parts within 72 hours.[9] The resulting polyps then attach themselves to the substrate and grow a full complement of 24 tentacles. About a month later they become detached, the multiple tentacles are reabsorbed and the four tentacles typical of the medusa phase develop.[4][9]

References

- Cornelius, Paul (2014). "Carybdea marsupialis (Linnaeus, 1758)". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- Marsupialis denotes "having a pouch", from the Late Latin marsupium, "pouch".

- Riedl, R. (1991). Muzzio, Franco (ed.). Fauna e flora del Mediterraneo. pp. 148–150.

- Ziemski, Frédéric; Prouzet, Anne. "Carybdea marsupialis (Linnaeus, 1758)" (in French). DORIS. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

- Straehler-Pohl, I.; G.I. Matsumoto; M.J. Acevedo (2017). "Recognition of the Californian cubozoan population as a new species Carybdea confusa n. sp. (Cnidaria, Cubozoa, Carybdeida)". Plankton Benthos Res. 12 (2): 129–138.

- Bordehore, C.; S. Nogué; J.-M. Gili; M.J. Acevedo; V.L. Fuentes (2014). "Carybdea marsupialis (Cubozoa) in the Mediterranean Sea: The First Case of a Sting Causing Cutaneous and Systemic Manifestations". Journal of Travel Medicine. 22 (1): 61–63. doi:10.1111/jtm.12153.

- G.O. Mackie (31 December 1976). Coelenterate Ecology and Behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-306-30991-5.

- Canepa, A. (2017). "Environmental factors influencing the spatio-temporal distribution of Carybdea marsupialis (Lineo, 1978, Cubozoa) in South-Western Mediterranean coasts". PLoS One. 12 (7): e0181611. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181611. PMC 5528890.

- Daphne G. Fautin; Jane A. Westfall; P Cartwright; Marymegan Daly; C R Wyttenbach (7 November 2007). Coelenterate Biology 2003: Trends in Research on Cnidaria and Ctenophora. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-4020-2762-8.