Carrières Centrales

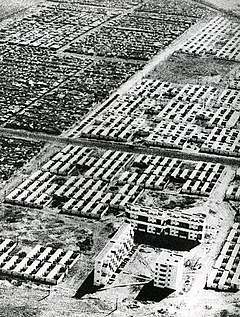

Carrières Centrales (Moroccan Arabic: كريان سنطرال) is a series of modernist housing developments in Casablanca, Morocco designed in the 1950s by architects Georges Candillis, Shadrach Woods, Alexis Josic.[1] The development aimed to create utopian "habitats" that would provide alternatives to slum life for working class residents of the city. Carriere Centrale has been noted as a prominent example of modernism within the Maghreb.[1]

| Carrières Centrales | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | Hay Mohammadi

|

| Coordinates | 33.583°N 7.564°W |

| Completed | 1952 |

History

Michel Écochard was appointed Director of the Service de l’Urbanisme et de l’Architecture of French Morocco in 1946. Following a multidisciplinary study of the nation's housing needs, Écochard established a plan to develop a number of housing projects for the working poor at the outskirts of Morocco's major cities. Écochard conceived of a substantial program that included a specially designed 8 x 8 meter grid plan.[2]

Carrières Centrales, a site the Hay Mohammadi district of Casablanca, was the first project to test Écochard's design. The development aimed to provide affordable housing for individuals working in a nearby factory and French homes.[2][3]

In 1952, Georges Candilis, Shadrach Woods, and Alexis Josic—the architects Écochard assigned to the project—designed a series of utopian modernist modular complexes for the site that additional educational, administrative, and religious facilities.[2] Influenced by Le Corbusier's Unité d'habitation and the communal nature of slum life, the resulting mid-rise complexes featured highly collective multilevel living exemplified by myriad balconies.[4][5] The site's buildings became known by the residents as Semiramis and Nid D'Abeille as references to their visual similarities to honeycombs and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon respectively.[6]

Since their construction, many of the complex' residents have modified the buildings significantly, most frequently by walling off the original balconies.[1]

References

- Ferrantea, Annarita (2011). "Retrofitting and adaptability in urban areas" (PDF). Procedia Engineering. 21.

- "Amènagement Urbain de la Ville de Casablanca | South section, Carrières centrales". Archnet. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- "The Housing Grid by Michel Ecochard | Model House". transculturalmodernism.org. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- Heuvel, D. van den; Mesman, M.; Quist, W. (2008-09-11). The Challenge of Change: Dealing with the Legacy of the Modern Movement: Proceedings of the 10th International DOCOMOMO Conference. IOS Press. ISBN 9781607503712.

- Teerds, Hans (2005-12-15). "Candilis-Josic-Woods: dialectic of modernity". ArchiNed (in Dutch). Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- Heuvel, D. van den; Mesman, M.; Quist, W. (2008-09-11). The Challenge of Change: Dealing with the Legacy of the Modern Movement: Proceedings of the 10th International DOCOMOMO Conference. IOS Press. ISBN 9781607503712.