Carolines Question

The Carolines Question (or the Carolines Crisis) was a conflict between the German Empire and the Kingdom of Spain over the sovereignty of the Caroline Islands and Palau in the western Pacific. It took place in 1885, at the beginning of the German colonial empire and towards the end of the Spanish Empire.

Background

Spain had regarded the Caroline Islands as part of the Spanish East Indies ever since the Age of Discovery, when the Treaty of Zaragoza had marked it out as part of the Spanish sphere of influence. Nevertheless, Spain did not exercise effective control over the Islands, and in 1875 Spain agreed with Germany not to extend the customs jurisdiction of the Philippines over the Islands, thereby assuring free trade for German businesses in the Pacific.

The Anglo-German agreement of April 1884 recognised Kaiser-Wilhelmsland and the islands to its north as part of the German sphere of influence and in November 1884 the German flag was raised on Mioko Island in the future Bismarck Archipelago.[1] These developments brought German interests more closely and assertively into contact with those of Spain. The Anglo-German agreement only defined the zones of influence of the two signatory powers and did not clarify any other limits on German power.

On 23 January 1885 the Hamburg firm of Hernsheim & Co asked the German government to take the Caroline Islands under protection in order to secure its trading monopoly.[2] The Colonial advisor in the Foreign Office, Friedrich Richard Krauel, endorsed this proposal and forwarded it to the Under-Secretary, Herbert von Bismarck.[3] His father, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, believed that Spain was about to formally annexe the Caroline Islands in response to German expansion.[4] In June 1885 the rumour spread that Spain would bring the Islands under effective occupation and had already named a governor. On 21 July 1885 Kaiser Kaiser Wilhelm I approved the German occupation of the Carolines.

Raising the flag

Bismarck confirmed to the German Admiralty that the flag should be raised over the Carolines. On 31 July 1885 Lieutenant Commander Paul Hofmeier, in command of the gunboat Iltis off Shanghai, was ordered to carry out the raising of the flag on Yap and Palau and to secure treaties of protection with local chiefs to legitimise German occupation.

On 4 August 1885, the German authorities informed the Spanish Government that they were extending the area of German protection to the Carolines. Spain's Foreign Minister José de Elduayen y Gorriti immediately rejected Germany's right to take this step. The Spanish government sent Berlin a note, affirming that the Carolines had belonged to Spain since 1543. A few days later, however, Spain guaranteed freedom of trade for Germans in the Carolines. A hostile press campaign began in Spain, which resulted in anti-German protests. There were demonstrations in Madrid, where a rally attracted over 30,000 people, and around 80 other places in the country.

The Carolines Question allowed Spain's Republican opposition to embarrass King Alfonso XII, which meant that his government wanted the matter resolved quickly. Bismarck, surprised by the scale of the protests, announced on August 23, 1885 that Germany had no intention of negating established historic rights and proposed to take the matter to arbitration. However Spain produced no evidence of prior ownership and Bismarck was in no hurry to conclude matters before receiving a report from the German navy.

On the evening of 2 August 1885 when the German gunboat Iltis steamed into the harbour at Yap, it found two Spanish warships, the San Quentin and the Manila at anchor.[5]:412 They had brought the future Spanish governor as well as priests and soldiers to the island, and construction of a Spanish government post had already begun. Nevertheless, Hofmeier had the German flag raised, which prompted the Spaniards to raise their own flag. It seemed that a fight would follow, but the Spanish withdrew and left the island.[4]

Commercial concerns

When news of the German flag-raising reached Madrid at the beginning of September 1885, riots broke out around the German embassy. The German consulate in Valencia also found itself the target for angry attacks.[4] With the threat that the situation could get out of control, the Spanish government urged Germany to find an early solution. Meanwhile, the gunboat Albatross under Corvette Captain Max Plüddemann continued to raise the German flag and visited many of the Caroline Islands between 20 September and 18 October 1885.[6]

However, by now Bismarck feared that in the event of war with Spain, France would side with her against Germany. At the same time, the impute was having a damaging effect on German-Spanish trade relations (the volume of trade had increased around tenfold since 1879).[7] This was of greater importance than the possession of the Carolines' possession ever promised. Spain played upon German commercial concerns by promising an advantageous trade agreement for Germany in return for recognising Spanish sovereignty.

Arbitration

Bismarck continued to insist on independent arbitration, as the only alternative was to recognise that Spain was in the right. On September 29, 1885, Bismarck proposed Pope Leo XIII as arbitrator, as one whose authority Catholic Spain could scarcely deny. At the same time, Bismarck hoped to restore relations with the Holy See after the bitter divisions of the kulturkampf. The Pope pronounced his verdict on 22 October 1885; as expected, he determined that the islands were Spanish. He also directed the Spanish government to set up a functioning administration as soon as possible, and granted Germany freedom to trade and settle in the Carolines as well as a possible coal and naval station on Yap.[8] This however Germany never claimed. The Pope's verdict took no account of the wishes of the islanders themselves.

The existing trade agreement between Germany and Spain was renewed on December 7, 1885, and on 17 December a new German-Spanish Treaty, was signed in Rome, giving effect to the Pope's decision. This brought the Carolines Question to a close.[9]

Aftermath

German reactions to this outcome ranged from anger at a second defeat after the Kulturkampf to praise for peaceful arbitration. Indeed, the anti-colonial German Free-minded Party even saw it as a sign of the early the end of German colonialism. In Spain, discontent reigned over the concessions made to Germany. This was expressed in a popular play in which the children named ‘Hispania’ and ‘Germania’ argued over a doll named ‘Carolina’ until their father came and declared that although the doll belonged to ‘Hispania’, ‘Germania’ was to play with her.

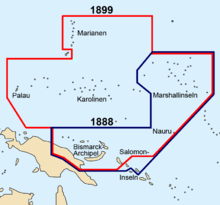

The Carolines Question brought the Micronesian islands into the light of international interests. Away from the areas over which Spain successfully asserted its sovereignty, on October 15, 1885, the commander of the German gunboat Nautilus declared the still independent Marshall Islands to be a German protectorate.[10][5]:342

In also taking Nauru (1888), Germany had secured control of all the islands south and west of the Carolines. In 1887 Spain began to exercise effective control over the Carolines, meeting opposition from the inhabitants as it did so.[11]

Following the Spanish–American War Spain sold the Carolines, Palau and the northern Marianas to Germany in the German–Spanish Treaty (1899) for 16.6 million marks. The islands became part of the German colonies in the Pacific, until they were occupied by Japan in 1914 and, after the First World War were ruled by Japan under the South Seas Mandate.

References

- Kanasa, Biama (June 2006). "Borders across rivers: Problems with the Creation of Anglo- German Border across Gira, Eia, Wuwu, and Waria Rivers, 1884-1909". Transforming Cultures eJournal. 1 (2): 160. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.547.5968. doi:10.5130/tfc.v1i2.273.

- Beier, Birgitt (1983). Die Chronik der Deutschen. Dortmund: Chronik-Verlag. p. 630. ISBN 3-88379-023-0.

- Friedrich von Holstein (2 January 1957). The Holstein Papers: Volume 2, Diaries: The Memoirs, Diaries and Correspondence of Friedrich Von Holstein 1837-1909. Cambridge University Press. pp. 234–7. ISBN 978-0-521-05317-4.

- Francis X. Hezel (1994). The First Taint of Civilization: A History of the Caroline and Marshall Islands in Pre-colonial Days, 1521-1885. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 308–12. ISBN 978-0-8248-1643-8.

- Boelcke, Willi A. (1981). So kam das Meer zu uns – Die preußisch-deutsche Kriegsmarine in Übersee 1822 bis 1914. Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Vienna: Ullstein. ISBN 3-550-07951-6.

- "Annexation of the Carolines". The Brisbane Courier. 17 November 1885. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Volker Schult (2008). Wunsch und Wirklichkeit: deutsch-philippinische Beziehungen im Kontext globaler Verflechtungen 1860-1945. Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-8325-1898-1.

- Eirik Bjorge (17 July 2014). The Evolutionary Interpretation of Treaties. OUP Oxford. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-19-102576-1.

- Linda J Pike (28 June 2014). Encyclopedia of Disputes Installment 10. Elsevier. pp. 505–. ISBN 978-1-4832-9494-0.

- Francis X. Hezel (September 2003). Strangers in Their Own Land: A Century of Colonial Rule in the Caroline and Marshall Islands. University of Hawaii Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8248-2804-2.

- Schnee, Heinrich, ed. (1920). Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon. II. Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer. pp. 237ff. Retrieved 23 February 2019.