Carmo Convent

The Convent of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Portuguese: Convento da Ordem do Carmo) is a former Catholic convent located in the civil parish of Santa Maria Maior, municipality of Lisbon, Portugal. The medieval convent was ruined during the sequence of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, and the destroyed Gothic Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Portuguese: Igreja do Carmo) on the southern facade of the convent is the main trace of the great earthquake still visible in the old city.

| Convent of Our Lady of Mount Carmel | |

|---|---|

| Carmo Convent | |

Convento da Ordem do Carmo | |

View on the apse of the Carmo Convent (as seen from the Rossio square) | |

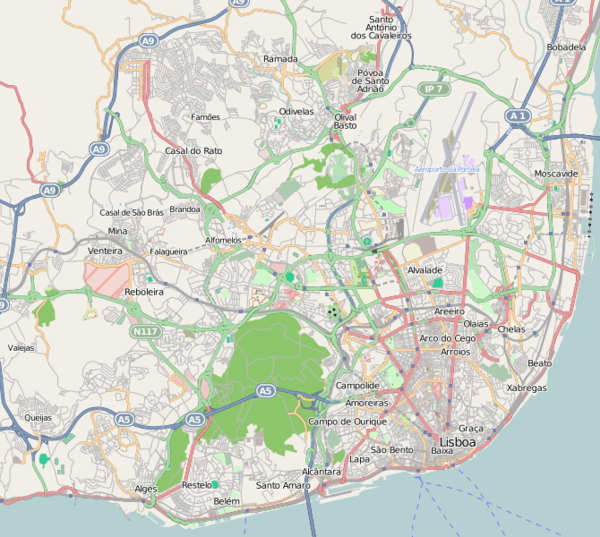

Convent of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Location of the convent within the municipality of Lisbon | |

| 38°42′44″N 9°8′24″W | |

| Location | Lisbon, Greater Lisbon, Lisbon |

| Country | Portugal |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Afonso Eanes, Gonçalo Eanes, Rodrigo Eanes, Leonel Gaia |

| Style | Gothic |

| Years built | 1389 |

History

The monastery was founded in 1389 by the Constable D. Nuno Álvares Pereira (supreme military commander of the King),[1] from the small Carmelite convent situated on lands acquired from his sister Beatriz Pereira and the admiral Pessanha. The reconstruction of the convent began sometime in 1393.[2]

In 1407 the presbytery and apse of the conventual church was completed, allowing the first liturgical acts in that year.[2] By 1423 the residential cells were completed, allowing the Carmelites friars from Moura (southern Portugal) to inhabit the building, including Father Nuno de Santa Maria, the Constable D. Nuno Àlvares Pereira who donated his wealth to the convent and entered the convent.[2]

By 1551, the convent contained 70 clergy and 10 servants, paying land rents of approximately 2500 cruzados annually.[2]

In 1755, an earthquake off the coast of Portugal caused significant damage to the convent and completely destroyed the library, which housed approximately 5000 volumes.[2] The 126 clerics at the time were forced to abandon the building, transferring initially to Cotovia, then to Campo Grande.[2]

.jpg)

Minor repairs to the monastery were carried out in 1800; roof tiles were repaired at this time. Ten years later, the monastic site was occupied by quarters of the Guarda Real de Polícia (Police Royal Guard), including eventually, the garrisoning of the sharpshooter battalion (in 1814) and the militia (in 1831), following painting its interiors.[2] In 1834, there were repairs by the Public Works department to adapt the convent to receive the Tribunal do Juízo de Direito do 3º Distrito (3rd District Judges' Law Court). The church was never fully rebuilt and rented out as sawmilling shop (in June 1835), before the religious orders were expelled from the country.[2] At that time the first and second companies of infantrymen for the municipal guard were stationed at the convent and, later, the first cavalry squadron in 1845. The buildings and site were donated in 1864 to the Association of Portuguese Archaeologists, which turned the ruined building into a museum.[2]

In 1902, a team was given the responsibility for restoring the facade along the Largo do Carmo.[2]

Between 1911 and 1912, the walls around the Carmo Convent were reconstructed, with various arches built, under the guidance of architect Leonel Gaia.[2]

In 1955, permission was given to execute public projects to conserve and restore the facades and roofing of the garrison buildings, by the Delegação nas Obras de Edifícios de Cadeias das Guardas Republicana e Fiscal e das Alfândegas (Republican Guard Delegation for Prison Buildings and Customshouses).[2]

On 28 February 1969, an earthquake caused damage to the church nave.[2]

During the events of the Carnation Revolution the convent was encircled by military rebels, who opposed the Estado Novo regime.[2] The regime's last President, Marcelo Caetano, and forces loyal to his regime were holed-up in the buildings, and eventually surrendered to the future democratic President António de Spínola.[2] The old convent was eventually transformed into the headquarters of the Republican Guard (Guarda Republicana).

Architecture

The Carmo Convent and its Church were built between 1389 and 1423 in the plain Gothic style typical for the mendicant religious orders. There are also influences from the Monastery of Batalha, which had been founded by King John I and was being built at that same time. Compared to the other Gothic churches of the city, the Carmo Church was said to be the most imposing in its architecture and decoration.

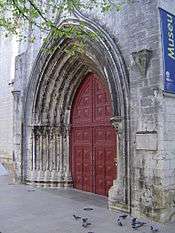

The church has a Latin cross floorplan. The main facade has a portal with several archivolts and capitals decorated with vegetal and anthropomorphic motifs. The rose window over the portal is partially destroyed. The south side of the church is reinforced by five flying buttresses, added in 1399 after the south wall collapsed during the construction work. The old convent, located to the right of the facade, was rebuilt in neo-Gothic style in the early 20th century.

The church interior has a nave with three aisles and an apse with a main chapel and four side chapels. The stone roof over the nave collapsed after the earthquake and was never rebuilt, and only the pointed arches between the pillars have survived.

The Carmo Convent is located in the Chiado neighbourhood, on a hill overlooking the Rossio square and facing the Lisbon Castle hill. It is located in front of a quiet square (Carmo Square), very close to the Santa Justa Lift.

Museum

Nowadays the ruined Carmo Church is used as an archaeological museum (the Museu Arqueológico do Carmo or Carmo Archaeological Museum). The nave and apse of the Carmo Church are the setting for a small archaeological museum, with pieces from all periods of Portuguese history. The nave has a series of tombs, fountains, windows and other architectural relics from different places and styles.

The old apse chapels are also used as exhibition rooms. One of them houses notable pre-historical objects excavated from a fortification near Azambuja (3500–1500 BC).

The group of Gothic tombs include that of Fernão Sanches, a bastard son of King Dinis I, (early 14th century), decorated with scenes of boar hunting, as well as the magnificent tomb of King Ferdinand I (reign 1367-1383), transferred to the museum from the Franciscan Convent of Santarém. Other notable exhibits include a statue of a 12th-century king (perhaps Afonso Henriques), Moorish azulejos and objects from the Roman and Visigoth periods.

In popular culture

- In video games, Assassin's Creed Rogue (2014) featured the church as a location of a piece of First Civilization technology. When Shay Patrick Cormac, the protagonist of the game, attempts to secure this technology, the site collapses, causing the 1755 earthquake.

References

Notes

- Pereira served King John I, commanding the Portuguese army in the decisive Battle of Aljubarrota (1385), in which the Portuguese guaranteed their independence by defeating the Castilian army.

- Vale, Teresa; Gomes, Carlos (1996), SIPA (ed.), Convento do Carmo/Comando Geral da Guarda Nacional Republicana, GNR, do Carmo (IPA.00005069/PT031106270328) (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico, archived from the original on 1 February 2016, retrieved 31 January 2016

Sources

- Ana, José Pereira de Santa (1745), Chronica dos Carmelitas da Antiga e Regular Observância dos Reinos de Portugal, Algarve e Seus Domínios (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Araújo, Norberto de, Peregrinações em Lisboa (in Portuguese), 2, Lisbon, Portugal

- Brandão, Cunha (1908), As Ruínas do Carmo (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Caeiro, Baltazar Matos (1989), Os Conventos de Lisboa (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- História dos Mosteiros, Conventos e Casas Religiosas de Lisboa (in Portuguese), I, Lisbon, Portugal, 1950

- Martins, João Paulo (2004), "Arquitectura contemporânea na Baixa de Pombal", Monumentos (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: DGEMN, pp. 142–151

- Mesquita, Alfredo (1903), Lisboa Illustrada (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Ministério das Obras Públicas, Relatório da Actividade do Ministério no ano de 1955 (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal, 1956

- Ministério das Obras Públicas, Relatório da Actividade do Ministério no ano de 1956 (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal, 1957

- Ministério das Obras Públicas, Relatório da Actividade do Ministério nos anos de 1957 e 1958 (in Portuguese), 1, Lisbon, Portugal, 1959

- Ministério das Obras Públicas, Relatório da Actividade do Ministério nos Anos de 1959 (in Portuguese), 1, Lisbon, Portugal, 1960

- Moita, Irisalva (1988), "O Chiado. Seu Contexto Urbanístico e Sociocultural", Lisboa. Revista Municipal (in Portuguese) (Série 2 ed.)

- Pereira, Luis Gonzaga (1924), Monumentos Sacros de Lisboa em 1833 (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Pereira, Paulo (1988), "O Portal do Capítulo Novo do Convento do Carmo", Lisboa. Revista Municipal (in Portuguese) (Série 2 ed.), Lisbon, Portugal

- Portugal, Fernando; Matos, Alfredo (1974), Lisboa em 1758. Memórias Paroquiais de Lisboa (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Sequeira, Gustavo Matos (1941), O Carmo e a Trindade (in Portuguese), I/III, Lisbon, Portugal

- Vilela, Sá (1876), As Ruínas do Carmo. Breves Considerações (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Proença, Raul (1924), Guia de Portugal (in Portuguese), I, Lisbon, Portugal

External links

- Site of the Association of Portuguese Archaeologists with information on the Museum (in Portuguese).