Carl Breer

Carl Breer (8 November 1883 – 21 December 1970) was an American automotive industry engineer. Along with Fred M. Zeder and Owen Skelton, he was one of the core engineering people that formed the present day Chrysler Corporation.[3][4] He made material contributions to Tourist Automobile Company, Allis-Chalmers, Studebaker, and was the moving engineer behind the Chrysler Airflow. He was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame.[5]

Carl Breer | |

|---|---|

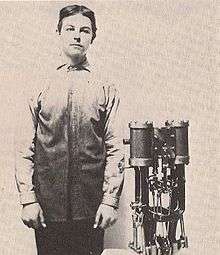

Carl Breer (1900, age 17) with homemade two cylinder steam engine for his 1901 car | |

| Born | 8 November 1883 [1] |

| Died | 21 December 1970 (aged 87)[2] |

| Occupation | Engineer, automobile designer |

| Political party | Democratic |

Early life and education

Breer was born in Los Angeles, California, on 8 November 1883.[6] He was from German descent. His father came from a village of the Hartz Mountains in Germany, while his mother came from a village of the Black Forest.[7][8] Breer was the youngest of 9 children in the family. He had 2 sisters and 6 brothers.[1][9] His father's name was Louis (b. 1828). His mother's name was Julia (b. 1840).[10]

Breer's father was born in 1828 and his mother was born in 1840. Breer's father was a skilled blacksmith refining his skills by traveling from village to village in Germany. At the age of 20, to avoid being selected for a three-year term in the German army, Breer's father moved to the United States just as he was turning 21. He moved about quite a bit for the first few years while in the United States, but ultimately settled in the Los Angeles area, where he lived for the rest of his life.[11]

Breer's mother was born in Ober-Owerisheim, Baden, Germany, located in the Black Forest. His mother and her younger sister moved to the United States to join an uncle who had a shipping business on the west coast of the United States. They settled also in the Los Angeles area. Breer's father and mother married in 1863.[11]

When Breer was a child growing up his family had a redwood cottage they stayed in for the summer months in Santa Monica, some 16 miles away that took about a three and a half hours one way by horse and buggy from their Los Angeles home.[12]

Career

Mid life

Breer participated in the operations at his father's blacksmith shop when he was a teenager and learned the basics of iron works. Here he acquired journeyman blacksmith skills.[13]

When Breer was 14 years old in 1897 he was given a personalized tour of the Los Angeles Water Works pumping plant by the chief engineer, Fred J. Fisher. During the tour he noticed an innovation that Fisher made – a homemade electric generator to generate electricity for light bulbs in the dark corners of the plant. Mr. Fisher became Breer's mentor. He would often visit him at the plant on weekends and when out of school. He copied Fisher's generator, using it to light his family's home. This was Breer's first inspiration for engineering.[14]

Steam-powered car

Breer was 17 years old in 1900 when he was inspired to build a motor-driven car. The inspiration came when he saw a Duryea car in his neighborhood. He confided in Fisher and they decided to build a steam engine for the new car, since Breer's blacksmithing experience had given him some understanding of what was needed. Using Stanley Steamer designs from a magazine as an initial guide, he roughed-out a two-cylinder steam engine, from which he drew detailed sketches of the component parts. He took the drawings and a wood-carved model of the cylinder block to a foundry to be cast. When the foundry failed on several attempts to make the casting, Breer asked if he could try using their facilities — and made a satisfactory cylinder on his first attempt.[8][15]

Breer made additional parts needed for the steam engine. One piece was a Bunsen-type burner fueled by gasoline to heat the boiler for the steam. This required about 3,000 small holes to be drilled into the inner chamber of the air tubes. Since there was no drill that could do this, Breer improvised a high-speed Pelton type drill press that operated on water pressure from their outdoor water faucet. With his innovation, the holes were drilled in a short time. Breer assembled his car in 1901, with some help in upholstery, trimming and painting the car supplied by hired carriage workers. The maiden voyage of Breer's steam car was made in the fall of 1901.[8][16]

Several improvements were made to the car over the next few years. One was a spare gas tank for the boiler, so that he could go trout fishing with his brother Bill at San Gabriel Canyon near Azusa, California—some 35 miles away on rough dirt roads, a trip not possible with horse and buggy. Breer registered his car, as was required by Los Angeles for all horseless carriages, and obtained a favored locomotive number, 666.[8][17]

Breer rated his steam car at 25–35 miles per hour or about twice the speed of a horse. His car was more efficient than a horse for long-distance travel and hill climbing. While his steam car was more effective this way, it was determined by English engineers that steam-powered cars were less effective than gasoline-powered cars. They conclude they could not compete with gas cars under a 1,000 horsepower rating. Also a gasoline car would start instantly, where a steam-powered car took time to build up its power. A gas car was more efficient in miles per gallon and a more compact vehicle. These reasons motivated some steam-powered car companies to convert to gasoline vehicles.[18]

Career

He was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 1976.[5]

The Tourist Automobile Company

Breer wanted a job and experience, so he applied at the Tourist Automobile Company (a major United States west coast manufacturer of automobiles at the time), located then at North Main and Alameda Street in Los Angeles.[6] He had no prior job experience to offer to the head of the service garage, but demonstrated his steam car he made that he drove there. This obtained for him the first official engineering job during his summer vacations from high school to demonstrate, service and design. This led to other similar job opportunities from East Coast steam-powered automobiles such as Toledo Steam Cars, the Spalding, the Northern, and the White Steamer. On the west coast, he was also a developer of the cutting edge two-cylinder Duro car.[1][7][8]

Los Angeles Commercial High School that he attended had no credit standing for an official mechanical engineer. In 1904 he drove his steam car from Los Angeles to Pasadena and showed it to Throop Polytechnic Institute (forerunner of Caltech). The school enrolled him in a one-year term which he completed with full credits as a mechanical engineer. He then qualified to be able to go to Stanford University in the fall of 1905 to learn advanced mechanical engineering.[8][19]

Allis-Chalmers

Breer went to Stanford University, graduating in 1909, and became a mechanical engineer. He soon received a job opportunity from Allis-Chalmers of West Allis, Wisconsin near Milwaukee and initially went through their two-year apprenticeship course. Allis-Chalmers selected twenty-five of the best students of mechanical engineering from top universities of the United States. Besides Breer, Frederick Morrell Zeder was such a student. Zeder was from the University of Michigan. Breer and Zeder became close friends in their training at Allis-Chalmers.[1][7][8]

Studebaker

Breer moved to the west coast in 1911 and worked for the Moreland Motor Truck Company. In 1914 he helped organize the Home Electric Auto Works company (a service and accessory business), but soon lost interest in the company and sold out to his partner. He then built for himself a combination experimental garage and shop in 1916. In this same year he received a letter from his friend Fred Zeder asking if he would be interested in joining him at Studebaker to organize a research division. Zeder was then chief engineer at Studebaker and was developing a new engineering department for them. He also invited Owen R. Skelton to Studebaker, bringing together the Zeder-Skelton-Breer engineering team, which came to be known as "The Three Musketeers".[1][7][8]

Zeder's job was to develop engineering that replaced the obsolete Studebaker models. The engineers worked together efficiently and produced cutting-edge engineering technology that resulted in immediate profits for Studebaker. The "Big Six" Studebaker 1918 spring models came with such things as a unique clutch, lower center of gravity design, and detachable cylinder heads. Studebaker was so confident of the new technology that they discontinued making horse-drawn carriages in 1919.[20]

Breer formed a close relationship with Fred M. Zeder and later with Owen R. Skelton. They all had an engineering background. Skelton's expertise was as a technical engineering design analyst. Breer had the capacity to solve difficult technical engineering problems (especially in engines) with existing technology, and Zeder was a capable administrator and salesman as well as an engineer. Breer was the oldest of the three.[1]

World War I

Studebaker was involved in World War I obligations and built tanks for the United States Army. Breer was given the assignment of working on Liberty aircraft engines of the De Havilland biplane for the government during the end of World War I. His responsibility was to discover why the aircraft engines would break up and come apart. His work was analyzing the 50-hour engine tests. Many pilots were lost during the war because the engine would explode for no apparent reason within 50 hours. Breer eventually found that metal fatigue on certain connecting rods that came apart, then broke other parts. He was able to solve the problem eventually, but by then the war was over and the solution had no benefit for World War I pilots. However the solution was beneficial to pilots that followed, the airmail carriers particularly.[8][21]

Walter P. Chrysler association

Walter P. Chrysler had just left Buick and General Motors and joined Willys enterprises as their vice-president in January 1920. Chrysler asked the Breer, Zeder and Skelton if they wanted to join him at Willys-Overland. Breer with his two cohort engineers made several business trips to New York and the new cutting edge high-tech Willys factory in Elizabeth, New Jersey. The three elite engineers decided this would be an excellent move for them - and 28 other engineers from Studebaker (creme-de-la-creme). They all went to work designing a new car for Willys-Overland – the "Chrysler". It was soon discovered that the Willys Corporation was out of money due to one of their branches taking all the reserves. Willys was bankrupt. Chrysler resigned from Willys in 1922 and became chairman of the board for Maxwell Motor Company.[22]

Breer and his two cohorts formed a consultant business located in Newark, New Jersey - The Zeder, Skelton and Breer Engineering Company (initially financed by Chrysler), which consisted of other engineers from Studebaker. They rented from the Willys receivers the laboratories they had already established at the high tech plant at Elizabeth, New Jersey. The plant went up for auction from receivership and William C. Durant bought it for $5.5 million. Even though Chrysler help them gert started in their consultant business, they contacted Durant for business since he bought the plant.[23]

Durant wanted his failed Mercer car plant in Scranton rejuvenated and asked the Zeder, Skelton and Breer Engineering Company to go there. After seeing the old brewery building where the cars were being made they decided against moving there. Breer and his cohort engineers settled on a deal with Durant instead to design a new engine for Durant's Locomobile, a car company Durant acquired in 1922. The company of high end automobiles for the Durant Motor Company went out of business, but not due to the engines which were satisfactory. Breer and his engineers then designed another engine for Durant, ultimately built by Continental Motors of Detroit. The plant where the actual automobile was built was located in Flint, Michigan. The "Flint car" was designed to compete with the Ford automobile and called the "Star". Breer and his cohorts had nothing to do with the "Star" car design, just the engine.[24][25]

In 1923 when Breer was on vacation with the family in California when Zeder and Skelton had a meeting with Mr. Chrysler in New York about the possibility of installing their engine in a new car and calling it a "Chrysler". The three engineers designed a car and started working with engineering at Maxwell Motor Company where Mr. Chrysler was the vice-president. It was to become Chrysler's first car,[26] the 1924 Model B Chrysler. The 'Three Musketeers' (Zeder, Skelton, and Breer) and their group of engineers (originally from Studebaker) were now working for Maxwell Motor Company. This new car with the three engineers' engine needed $5 million to start its production, which the Maxwell Motor Company did not have. The 1924 Chrysler car was to be shown at the 1924 New York Auto Show which likely would have produced and secured the loan necessary for production. Because the "Chrysler" was not in production it did not qualify to be shown. However Chrysler rented the lobby at the Hotel Commodore (the show's headquarters) and displayed the "Chrysler" there. The necessary financing was secured from Chase Securities Corporation. Chrysler produced 32,000 automobiles in 1924 and sold them for the same price as the Buick. The $5 million loan produced a profit of over $4 million. The Maxwell Motor Company was re-organized into the Chrysler Corporation in 1925.[27][28]

Airflow car

One day in the late twenties while driving Breer saw a formation of Republic Army planes flying low across the highway in the distance. This lead him to consider the idea of airflow and a relationship to cars. Wind tunnels for aeronautical purposes were very expensive, so one of the engineers consulted with Orville Wright. In a few months time they had made a 20 X 40 space as an aerodynamic lab for testing various shapes of small car models. The wind tunnel they built had a throat of 20 inches X 30 inches in cross section. The wind creating propellers were driven by a 35 hp motor that could be regulated for various speeds. The first models they tested were of production cars. The results were shown by black smoke from an oil lamp.[29]

When the aerodynamists were doing their tests, Breer suggested they test the models in the opposite direction. They were astonished to find that the air resistance drag was 30% less this way. Breer looking out a window then made the remark

Just think how dumb we have been. All those cars have been running in the wrong direction! [30][31]

This test resulted in the idea that an automobile shape should be like a blimp in front and taper off to a smaller section in the rear. This made air flow much more efficient since it then would be close to the body as it flowed toward the rear. Breer's idea of running a car in the opposite direction for streamlining was the birth of the Chrysler Airflow automobile.[30] The first experimental Airflow cars were the model Trifon of the later 1920s, prototypes done in secret. [32][33] The Airflow was first produced in 1934 and continued through 1937 when it was determined that the sales were so poor it was not worth producing.[5][34]

Popular wisdom is that the Airflow was a failure. While it is true that commercially it was unsuccessful, its massive change in profile, use of a modern (and heretofore unknown) space frame instead of a 'ladder chassis', and its reconfiguration of the auto's basic design and a massive redistribution of weight, all made it one of the most important car designs of the thirties. That it was ahead of its time, out of synch with popular taste, and did not sell does not diminish either its innovation or its artistic and technological merit and long term importance.[35]

Breer wrote in his published autobiography (Parts III - V) about the Airflow Car.[36]

Family

Carl's wife was Barbara, who was Fred Zeder's sister, whom he married in 1915.[6] She was shown as 7 years younger than Breer and they had one 1 child in the 1920 U.S. Census. The child was Carl Frederick (6 months old).[37] Carl and Barbara have 3 children (boys) reported in the 1930 U.S. Census.[38] In the late twenties the Breer family would often spend their summers at Gratiot Beach in Port Huron, Michigan, with their sons.[39] Carl and Barbara have 4 children reported in the 1940 U.S. Census, all boys.[6][40]

References

- Curcio 2001, p. 272.

- Carl Breer obituary, Detroit Free Press, Tuesday, Dec 22, 1970, p. 4-B

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. xi.

- Borth, Christy. Masters of Mass Production, p. 178, Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis, IN, 1945.

- "Carl Breer". Hall of Fame Inductees. Automotive Hall of Fame. 1976. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- Wilkie, David J. (October 22, 1939). "Engineer, Scientist Goal Held Still Beyond Horizon". The Ogden Standard-Examiner (p. 24). Ogden, Utah.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 1.

- Zatz, David (1998–2000). "Carl Breer, Executive Engineer". Allpar; allpar.com. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- Year: 1880; Census Place: Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California; Roll: 67; Family History Film: 1254067; Page: 206B; Enumeration District: 024; Image: 0115.

- Year: 1900; Census Place: Los Angeles Ward 7, Los Angeles, California; Roll: 90; Page: 2B; Enumeration District: 0073; FHL microfilm: 1240090.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 9.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 10.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 11.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 11,12.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 13, 14.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 15.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 18.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 18,19.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 21.

- Curcio 2001, p. 273.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 45-57.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 65-70.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 71.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 73-75.

- Kulchycki, T.L. (2000–2007). "The Locomobile Catalog". T.L. Kulchycki. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Wilkie, David J. (22 October 1939). "Man who built crude auto 40 years ago, now designer of the most modern 1940 car". The Palm Beach Post newspaper. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 76-79.

- Peterson. "A Brief Look at Walter P. Chrysler". The WPC Club. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 144.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 146.

- Breer, Carl. The Birth of Chrysler Corporation and Its Engineering Legacy, Part V. The Imperial Webclub. p. 146. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 151-153.

- Breer, Carl. The Birth of Chrysler Corporation and Its Engineering Legacy, Part V. The Imperial Webclub. p. 151. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, pp. 161-163.

- "Carl Breer". Coachbuilt. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- Breer, Carl. "The Birth of Chrysler Corporation and Its Engineering Legacy". The Imperial Webclub. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- Year: 1920; Census Place: Detroit Ward 8, Wayne, Michigan; Roll: T625_809; Page: 6B; Enumeration District: 263; Image: 145.

- Year: 1930; Census Place: Detroit, Wayne, Michigan; Roll: 1043; Page: 5A; Enumeration District: 312; Image: 1094.0; FHL microfilm: 2340778.

- Breer & Yanik 1994, p. 143.

- Year: 1940; Census Place: Grosse Pointe Park, Wayne, Michigan; Roll: T627_1829; Page: 9A; Enumeration District: 82-70A.

Bibliography

- Breer, Carl; Yanik, Anthony J, Editor (1994), The Birth of Chrysler Corporation and Its Engineering Legacy (illustrated ed.), Warrendale, PA 15096-0001: Society of Automotive Engineers, ISBN 1560915242CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) ISBN 978-1560915249

- Curcio, Vincent (2001), Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius (illustrated ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195147057CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)