Caloris Planitia

Caloris Planitia /kəˈlɔːrɪs pləˈnɪʃ(i)ə/ is a plain within a large impact basin on Mercury, informally named Caloris, about 1,550 km (960 mi) in diameter.[1] It is one of the largest impact basins in the Solar System. "Calor" is Latin for "heat" and the basin is so-named because the Sun is almost directly overhead every second time Mercury passes perihelion. The crater, discovered in 1974, is surrounded by the Caloris Montes, a ring of mountains approximately 2 km (1.2 mi) tall.

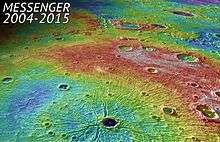

.png) Mosaic of the Caloris basin based on photographs by the MESSENGER orbiter. | |

| Planet | Mercury |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 30.5°N 189.8°W |

| Diameter | 1,550 km (963 mi) |

| Eponym | Latin for "heat" |

Appearance

Caloris was discovered on images taken by the Mariner 10 probe in 1974. Its name was suggested by Brian O'Leary, astronaut and member of the Mariner 10 imagery team.[2] It was situated on the terminator—the line dividing the daytime and nighttime hemispheres—at the time the probe passed by, and so half of the crater could not be imaged. Later, on January 15, 2008, one of the first photos of the planet taken by the MESSENGER probe revealed the crater in its entirety.

The basin was initially estimated to be about 810 mi (1,300 km) in diameter, though this was increased to 960 mi (1,540 km) based on subsequent images taken by MESSENGER.[1] It is ringed by mountains up to 2 km (1.2 mi) high. Inside the crater walls, the floor of the crater is filled by lava plains,[3] similar to the maria of the Moon. These plains are superposed by explosive vents associated with pyroclastic material.[3] Outside the walls, material ejected in the impact which created the basin extends for 1,000 km (620 mi), and concentric rings surround the crater.

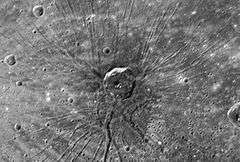

In the center of the basin is a region containing numerous radial troughs that appear to be extensional faults, with a 40 km (25 mi) crater, Apollodorus, located near the center of the pattern. The exact cause of this pattern of troughs is not currently known.[1] The feature is named Pantheon Fossae.[4]

Formation

The impacting body is estimated to have been at least 100 km (62 miles) in diameter.[5]

Bodies in the inner Solar System experienced a heavy bombardment of large rocky bodies in the first billion years or so of the Solar System. The impact that created Caloris must have occurred after most of the heavy bombardment had finished, because fewer impact craters are seen on its floor than exist on comparably-sized regions outside the crater. Similar impact basins on the Moon such as the Mare Imbrium and Mare Orientale are believed to have formed at about the same time, possibly indicating that there was a 'spike' of large impacts towards the end of the heavy bombardment phase of the early Solar System.[6] Based on MESSENGER's photographs, Caloris' age has been determined to be between 3.8 and 3.9 billion years.[1]

Antipodal chaotic terrain and global effects

The giant impact believed to have formed Caloris may have had global consequences for the planet. At the exact antipode of the basin is a large area of hilly, grooved terrain, with few small impact craters that are known as chaotic terrain (also "weird terrain").[7] It is thought by some to have been created as seismic waves from the impact converged on the opposite side of the planet.[8] Alternatively, it has been suggested that this terrain formed as a result of the convergence of ejecta at this basin's antipode.[9] This hypothetical impact is also believed to have triggered volcanic activity on Mercury, resulting in the formation of smooth plains.[10] Surrounding Caloris is a series of geologic formations thought to have been produced by the basin's ejecta, collectively called the Caloris Group.

Emissions of gas

Mercury has a very tenuous and transient atmosphere, containing small amounts of hydrogen and helium captured from the solar wind, as well as heavier elements such as sodium and potassium. These are thought to originate within the planet, being "out-gassed" from beneath its crust. The Caloris basin has been found to be a significant source of sodium and potassium, indicating that the fractures created by the impact facilitate the release of gases from within the planet. The unusual terrain is also a source of these gases.[11]

Gallery

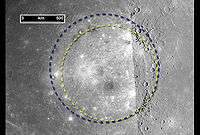

Topographic map of Caloris basin

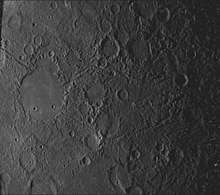

Topographic map of Caloris basin Mosaic of eastern Caloris basin photographed by Mariner 10 in 1974–75.

Mosaic of eastern Caloris basin photographed by Mariner 10 in 1974–75. Pantheon Fossae in the center of Caloris basin, with Apollodorus crater at center of the fossae.

Pantheon Fossae in the center of Caloris basin, with Apollodorus crater at center of the fossae.

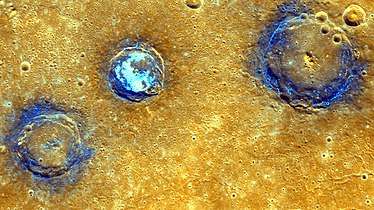

Perspective view of Caloris – high (red); low (blue).

Perspective view of Caloris – high (red); low (blue).

See also

- Geology of Mercury

- Skinakas basin

References

- Shiga, David (2008-01-30). "Bizarre spider scar found on Mercury's surface". NewScientist.com news service.

- Morrison D. (1976). "IAU nomenclature for topographic features on Mercury". Icarus. 28 (4): 605–606. Bibcode:1976Icar...28..605M. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(76)90134-2.

- Thomas, Rebecca J.; Rothery, David A.; Conway, Susan J.; Anand, Mahesh (16 September 2014). "Long-lived explosive volcanism on Mercury". Geophysical Research Letters. 41 (17): 6084–6092. Bibcode:2014GeoRL..41.6084T. doi:10.1002/2014GL061224.

- Mercury's First Fossae Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. MESSENGER. May 5, 2008. Accessed on July 13, 2009.

- Coffey, Jerry (July 9, 2009). "Caloris Basin". Universe Today. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- Gault, D. E.; Cassen, P.; Burns, J. A.; Strom, R. G. (1977). "Mercury". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 15: 97–126. Bibcode:1977ARA&A..15...97G. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.15.090177.000525.

- Lakdawalla, E. (19 April 2011). "Mercury's Weird Terrain". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- Schultz, P. H.; Gault, D. E. (1975). "Seismic effects from major basin formations on the moon and Mercury". The Moon. 12 (2): 159–177. Bibcode:1975Moon...12..159S. doi:10.1007/BF00577875.

- Wieczorek, Mark A.; Zuber, Maria T. (2001). "A Serenitatis origin for the Imbrian grooves and South Pole-Aitken thorium anomaly". Journal of Geophysical Research. 106 (E11): 27853–27864. Bibcode:2001JGR...10627853W. doi:10.1029/2000JE001384. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- Kiefer, W. S.; Murray, B. C. (1987). "The formation of Mercury's smooth plains". Icarus. 72 (3): 477–491. Bibcode:1987Icar...72..477K. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(87)90046-7.

- Sprague, A. L.; Kozlowski, R. W. H.; Hunten, D. M. (1990). "Caloris Basin: An Enhanced Source for Potassium in Mercury's Atmosphere". Science. 249 (4973): 1140–1142. Bibcode:1990Sci...249.1140S. doi:10.1126/science.249.4973.1140. PMID 17831982.