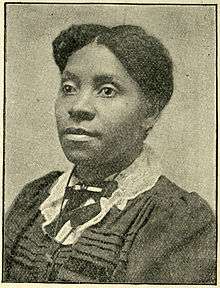

Callie House

Callie House (1861 – 1928) was a leader of the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association, one of the first organizations to campaign for reparations for slavery in the United States.[1]

Callie House | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1861 |

| Died | 1928 (aged 66–67) |

Biography

House was born a slave in Rutherford County, near Nashville, Tennessee. At the age of 22, she married William House. They had six children, five of which survived. After William died, House supported her family by being a washerwoman.[2]

National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty, and Pension Association

House and Isaiah H. Dickerson traveled ex-slave states to gather support for the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association (MRB&PA). They visited black churches—one of the few places blacks could organize without white interference.[2] MRB&PA was chartered August 7, 1897, with the goal of providing compensation to ex-slaves, mutual aid, and burial costs. At its peak, it claimed membership in the hundreds of thousands.

Despite lack of evidence, the federal Post Office Department accused slavery reparation organizations like MRB&PA of frauding their members. In 1899, the MRB&PA was forbidden to send mail or cash money orders. The Department of Justice opened an investigation of the MRB&PA. In 1901, Dickerson was found guilty of "swindling" but the conviction was later overturned. Upon Dickerson's death in 1909, House became the leader of the MRB&PA.[3] Despite interference with mails, the MRB&PA struggled on under House's leadership.[2]

The US Postal Service's accusations of fraud culminated in 1916 with House's arrest and subsequent sentencing to one year in prison in Jefferson City, Missouri. House's arrest dampened the national reparations movement, which struggled on through local branches until the 1930s.[4]

Legacy

In 2015 Vanderbilt University's African American and Diaspora Studies Program renamed its research arm the Callie House Research Center for the Study of Black Cultures and Politics.[5]

Further reading

- Mary Frances Berry, My Face Is Black Is True: Callie House and the Struggle for Ex-Slave Reparations, Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

- Ana Lucia Araujo, Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History, Bloomsbury, 2017.

References

- Statom, Virgil. "Callie House 1861-1928". Tennessee History Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society & University of Tennessee Press. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Berry, Mary Frances (2005). My Face Is Black Is True. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4003-5.

- Perry, Miranda. "No Pensions for Ex-Slaves: How Federal Agencies Suppressed Movement To Aid Freedpeople". archives.gov. National Archives. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- Berry, Daina Ramey; Kali Nicole Gross (2020). A Black women's history of the United States. Boston. ISBN 978-0-8070-3355-5. OCLC 1096284843.

- "Vanderbilt University Renames Black Studies Research Center After Former Slave and Early Reparations Activist Callie House". Good Black News. March 27, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.