California Water Plan

The California Water Plan (Water Plan) is the State of California’s long-term strategic plan for managing and developing water resources throughout the state. The Water Plan is mandated by California Water Code Sections 10004–10013,[1] and the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) is required to update the plan every five years.[2] Although the Water Plan does not create mandates, propose specific projects, or authorize funding, Water Code Section 10005 defines the plan and its updates as “the master plan which guides the orderly and coordinated control, protection, conservation, development, management and efficient utilization of the water resources of the state.”[3] Eleven updates to the plan have been prepared since 1957.

History

The development of water plans in California date back to the 19th century. Since then, they have taken several different formats and titles. The first plan was put together in 1873.[4] It covered ideas for water distribution in the state. In 1919, a report, titled “Irrigation of Twelve Million Acres in the Valley of California,”[5] provided the first comprehensive plan for water management. It is often referred to as the “Marshall Plan,” after its author, Col. Robert Bradford Marshall. In the decades following the release of that report, many water plans were issued as DWR bulletins (formal publications that include approved, official information to the governor, legislature, other government agencies, as well as the public).

The initial Water Plan (known as Bulletin 3)[6] was released in 1957 under the direction of DWR’s first director, Harvey Oren Banks (March 29, 1910 – September 22, 1996). A civil engineer, he was appointed State Engineer of California in 1955. A year later he was placed in charge of DWR. The Water Plan was intended for “the control, protection, conservation, distribution, and utilization of the waters of California, to meet present and future needs for all beneficial uses and purposes in all areas of the state to the maximum feasible extent.”[7] Gov. Pat Brown would later say it was to “correct an accident of people and geography.”[8]

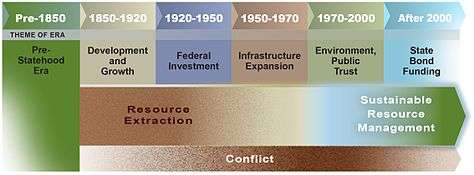

That first Water Plan, in 1957, and several updates that followed were, for the most part, technical documents focused on water supply development. The plans were gradually expanded to reflect the growing conflicts over California’s limited water resources.

In March 1966, Implementation of the California Water Plan[9] was released as Bulletin 160. All subsequent updates to the Water Plan have been issued under that bulletin number.

A new approach was established to produce the 1993 update. DWR worked with an advisory committee composed of a diverse group of stakeholders with the aim of making the Water Plan an all the “more technically accurate and politically balanced document.”[10] Beginning with the 1998 update, the Water Plan has moved beyond providing pure information to evaluating options for addressing future water shortages, even as extensive and early public input has been sought for each update. The approach involves dialogue and exchanges among Water Plan teams, committees, stakeholders, and the public. The sessions provide multiple opportunities for review by different audiences and feedback from a variety of perspectives. This transparent, collaborative, consensus-seeking process has been used by other agencies and states as a model for policy-planning efforts.

California Water Plan Update 2013[11] (Update 2013) had the added element of meshing[12] with Gov. Edmund G. Brown Jr.’s California Water Action Plan. The governor’s five-year plan, released in January 2014, outlines actions intended to bring reliability, restoration, and resilience to California’s water resources. It takes into account an anticipated population increase from the current 38 million, to an estimated 50 million by 2049.

Commitment to Integrated Water Management

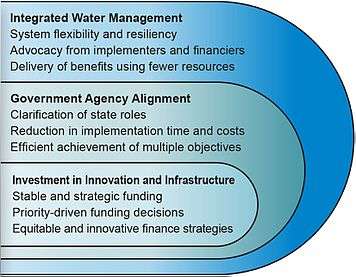

According to Chris Austin, of Maven’s Notebook, an independent and comprehensive source of California water news and information, “three related themes distinguish California Water Plan Update 2013.”[13] DWR and other State agencies consider the three themes critical to securing California’s water future.[14]

- Commit to Integrated Water Management: Integrated water management (IWM) promises to provide multiple benefits across the state’s diverse stakeholder communities and accelerate implementation of water projects by generating broader support.

Three Themes Graphic from Update 2013.

Three Themes Graphic from Update 2013. - Strengthen Government Agency Alignment: A key principle of IWM seeks to improve the way governments interact and ultimately deliver services. Aligning agencies in a collaborative manner, across jurisdictional boundaries at the appropriate geographic scale, provides for more efficiency in addressing water problems. The alignment would include management of data, planning, policy-making, and regulation across local, State, tribal, and federal governments.

- Invest in Innovation and Infrastructure: To reduce flood risk, provide reliable water supplies, and protect ecosystems, California will need up to $200 billion over the next 10 years just to maintain current levels of service and system conditions. It is projected that California will need up to $500 billion in future investment over the next few decades to reduce flood risk, provide reliable and clean water supplies, and restore and enhance ecosystems.[15]

The Santa Margarita Conjunctive Use Project in San Diego County is cited as an example of the three themes in action. This conjunctive use project is designed to provide for enhanced recharge of the groundwater basin beneath the Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton in northern San Diego County. It also includes a seawater intrusion barrier that uses recycled water, a distribution system, and advanced water treatment facilities. The project will provide a new water supply of about 6,800 acre feet (8.4×106 m3) per year for Camp Pendleton and Fallbrook Public Utilities District, and will resolve a long-standing water rights dispute between Fallbrook and the federal government.[16]

Update 2013 includes the Highlights booklet, three primary volumes, and two reference volumes.

Highlights: This booklet provides an overview of the first three volumes.

Volume 1 — The Strategic Plan: This volume looks at the current water issues in the state. It also provides a look at potential problems in the future, along with possible solutions. The Strategic Plan is presented in eight chapters, including “California Water Today” and “Roadmap for Action.”

Volume 2 — Regional Reports: California is divided into 10 hydrologic regions; this volume has a chapter on each one. There are also chapters on two overlay areas (the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Mountain Counties) that don’t qualify as hydrologic regions, but deserve attention because of their contributions and importance to California’s water systems.

Volume 3 — Resource Management Strategies: A comprehensive set of 30 resource management strategies makes up this volume. Each one discusses a technique, program, or policy that helps local agencies and governments manage their water. The strategies are divided into seven categories: Reduce Water Demand, Improve Flood Management, Improve Operational efficiency and Transfers, Increase Water Supply, Improve Water Quality, Practice Resource Stewardship, and People and Water.

Volume 4 — Reference Guide: This guide provides detailed reference material related to information presented in the first three volumes.

Volume 5 — Technical Guide: Organized and formatted as a Web portal, the Technical Guide documents the assumptions, data, analytical tools, and methods used to prepare Update 2013.

The next California Water Plan update is scheduled to be published in 2018. That version is expected to emphasize sustainability of water supplies, especially through the use of integrated water management and integrated regional water management. Other key themes will promote strengthening flood and river management. Update 2018 will also include, for the first time, a five-year State investment strategy and companion finance plan. It will be the first Water Plan update to “identify specific outcomes and metrics to track performance, prioritize near-term State actions and investments, recommend financing methods having more stable revenues, and inform water deliberations and decisions as they unfold.”[17]

References

- California Water Code Archived 2016-03-09 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Bill Number: SB 672, Chaptered, Bill Text. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Collaborative Versus Technocratic Policymaking: California’s Statewide Water Plan. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Report of the Board of Commissioners on the Irrigation of the San Joaquin, Tulare, and Sacramento valleys of the state of California. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- Irrigation of Twelve Million Acres in the Valley of California. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- A Century of Salt Water Barriers in the Delta. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- A Look Back at Past California Water Plans. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- California’s Pipe Dream: A Heroic System of Dams, Pumps, and Canals Can’t Stave Off a Water Crisis. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Implementation of the California Water Plan. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Collaborative Versus Technocratic Policymaking: California’s Statewide Water Plan. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- Public Outreach, Education and Engagement for State Water Planning: A Survey of Western States Water Council Members. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- A Resource for Implementing the Governor’s Water Action Plan. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- This just in … DWR releases the initial volumes and highlights of the California Water Plan. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- MEMO to Regional Council of Rural Counties Board of Directors Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- California eyes $500 billion in water spending Archived 2017-02-15 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Update Given on Santa Margarita Conjunctive Use Project. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- California Water Plan eNews. Retrieved 22 February 2016.