Calder's set for Socrate

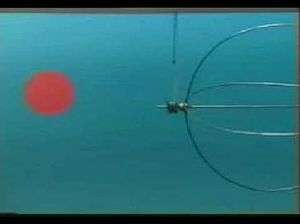

The original Decor for Satie's "Socrate" was designed by mobile artist Alexander Calder for a touring performance of Erik Satie’s symphonic drama Socrate in 1936. It was a mobile set considered by Virgil Thomson as one of the masterpieces of twentieth-century theatre design. It consisted of three elements: a red disc, interlocking steel hoops, and a vertical rectangle, black on one side and white on the other, against a blue backdrop. Destroyed in a fire in 1936, the decor was recreated by Walter Hatke in 1976 for a performance in New York.[1]

| Recreation of Decor for Satie’s “Socrate” (full scale), 1976 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Alexander Calder |

| Year | 1976 |

| Type | Mobile Set |

| Owner | Joel Thome |

Background

“A sense of drama is evident in much of Calder’s work, and his predilection for strong color, movement and large scale led naturally to the theater,” wrote Jean Lipman in the Whitney Museum of American Art catalogue Calder’s Universe .[2]

One of Calder’s first stage commissions was the mobile decor made in February 1936 for a production of Erik Satie’s Socrate at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, sponsored by a group with the amusing name the Friends and Enemies of Modern Music. The original Decor for Satie's "Socrate" was destroyed in a fire after the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center performance of Socrate in 1936.

Calder discussed the set in The Painter's Object saying : I did a setting for Satie’s Socrate in Hartford, U.S.A., which I will describe, as it serves as an indication of a good deal of my subsequent work.[3]

The set creation happened at a time when he was beginning to move from small, studio sculpture to large outdoor work, and Socrate gave Calder an opportunity to transpose his moving sculpture to monumental scale. He took the great empty space of the stage and filled it not only with forms but with the movement of those forms through space and time––an exercise more akin to dance than to sculpture.

Recreating the decor

In 1975, exactly forty years after he had asked Calder to make this Socrate set, Virgil Thomson found himself reminiscing about the Friends and Enemies of Modern Music with Joel Thome, director of the Philadelphia Composers Forum/Orchestra of Our Time. Thomson’s vivid description of the 1936 production of Socrate inspired Thome with the idea of re-creating Calder’s lost set. In May 1975 Thomson wrote to Calder at his home in France.

Within days the reply came: "It would be fun to revive that bit".[4] In October, Calder was in New York for his annual visit and exhibition at the Perls Galleries. Klaus and Dolly Perls arranged a meeting of Alexander Calder and Joel Thome and asked Jean Lipman and Richard Marshall, who were preparing for the Whitney Museum’s Calder retrospective, to join them. Calder gave Thome his permission for the revival. It was decided that the set would be built in two versions––one the original size and the other roughly one-third smaller––and that work would be done in New York by Walter Hatke, who worked at Perls Galleries.

The plans were sent to Calder in June 1976. He signed them and indicated that construction could proceed.[5] Using the drawings, Hatke set to work on a tabletop model and the 2:3-scale and full-scale recreations while Calder was in France.[6] In October Calder and Thome met again at Perls Galleries. Calder instructed the use of a blue cyclorama (The only important detail not in the 1937 sketch). About the lighting Calder concluded: "About the rest, you can use your imagination in a theatre." Calder asked Thome to pick him up on November 11 so that Calder could review the decor. As Thome was about to phone to confirm the time, he received word of Calder's sudden death.

The National Tribute to Alexander Calder

The production of Socrate was postponed for a year and reconceived as a memorial tribute to Alexander Calder. The recreated mobile was as much a part of the production as the music and script. The tribute performances took place at the Beacon Theatre in New York on the 10th and 11 November 1977, both of which were sold out.[7]

Lawsuit

The recreated set was the subject of a lawsuit brought by Joel Thome against the Calder Foundation.[8] Thome wished to sell the recreated set that Calder had "designed but did not live to see completed," which he had unsuccessfully tried to "get the Calder Foundation to authenticate."[9] The Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court rejected the appeal in 2009, finding that it did not have the power to declare the purported Calder work authentic nor to order the Calder Foundation to include it in the catalogue raisonné.[10]

References

- 'Short documentary'

- John Lipman Calder's Universe page 171

- "Mobiles by Alexander Calder in The Painter's Object edited by Myfanwy Evans" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2015-08-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Calder approval". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

- "Testimonial of Walter Hatke". Archived from the original on 2013-12-16. Retrieved 2013-12-16.

- Calders Sets in N.Y "Socrate" The Hour 26 October 1977

- Thome v. Alexander & Louisa Calder Found., No. 600823/07 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2008); aff’d 70 A.D.3d 88 (N.Y. App. Div. 2009)

- "Ruling on Artistic Authenticity: The Market vs. the Law" New York Times, August 2012

- Ralph E. Lerner and Judith Bresler, The Guide for Collectors, Investors, Dealers, & Artists, 548-550.