C. M. Battey

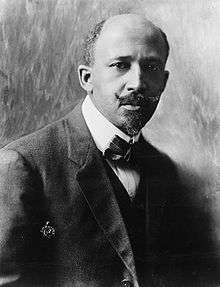

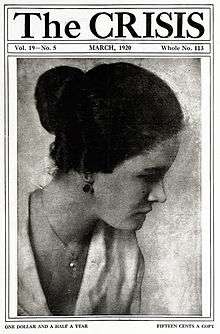

Cornelius Marion Battey (August 26, 1873 – March 14, 1927) was an American photographer who shot photographic portraits of black Americans in a pictorialist style. His photograph of black leaders appeared on the cover of the NAACP's magazine The Crisis beginning in the 1910s. He later founded and headed up the photography department at the Tuskegee Institute.

.png)

Early years

Cornelius Marion Battey was born on August 26, 1873 in Augusta, Georgia, but was raised in the North. His first job in photography was in a studio in Cleveland, Ohio. He moved to Manhattan, New York City and worked for six years in the Bradley Photographic Studio on Fifth Avenue, where he held the position of superintendent. He went on to work at Underwood & Underwood, one of the city's successful early 20th century photo studios, where he headed up the retouching department.[1]

Battey and Warren Studio

Battey eventually opened a business on Mott Street in New York with a white partner under the name Battey and Warren Studio.[1][2][3] He shot idealized photographic portraits of black people, some famous and some not. One of his earliest known photographs is of Frederick Douglass, shot in 1893 just two years before Douglass's death.[3] His style was pictorialist, characterized by use of soft focus and retouching of the negatives and prints to smooth out any irregularities.[1]

Battey became a friend of W. E. B. Du Bois, who was then editing The Crisis, the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[1] Battey's portraits of America's black leaders began regularly appearing on the cover of The Crisis.[1] He also shot covers for The Messenger magazine and the journal Opportunity.[2] As his fame grew, he also photographed white leaders such as President Calvin Coolidge and United States Supreme Court Chief Justice William Howard Taft.[1]

Starting around 1900, Battey began extensively documenting the life of Booker T. Washington, continuing until Washington's death in 1915.[4] Along with Arthur P. Bedou, he was one of the two photographers Washington most relied on, especially during northern trips.[5] Battey's formal, quiet studio portraits complemented Bedou's more journalistic, snapshot style.[5]

Tuskegee Institute

In 1916, Battey replaced Bedou as the official photographer of the Tuskegee Institute (of which Washington had been the founding principal). The administration favored him in part because it wanted to set up a photography department and Battey had connections with Eastman Kodak whose founder, George Eastman, had been a longtime supporter of the school.[5] Eastman donated funds to found the new department, which Battey then headed up until his death a decade later.[5] Battey taught courses in photography and at the same time documented the campus and its students and faculty, creating a unique record of black college life in the early twentieth century.[1] Among those he mentored was photographer P. H. Polk.

During his years at Tuskegee, Battey published a special edition of a print that visually linked four famous African-Americans with George Washington as a way of reclaiming black Americans' place in history.[5] Originally entitled Five Negro Immortals, the photogravure was published in 1911 as Our Heroes of Destiny and included Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, and Paul Laurence Dunbar.[6] Battey lost a substantial amount of money on the costly project, even though he also sold inexpensive versions of the print as well as marketing the individual portraits as frameable prints and postcards.[1][5]

In 1921, when the New York Public Library's 135th St. branch in Harlem held its first exhibition of work by black artists, "The Negro Artists", Battey was one of two photographers to have work in the show (the other being Lucy Calloway).[7]

Death

Battey died at Tuskegee, Alabama on March 14, 1927 in Cedar Grove Cemetery in Augusta, Georgia.[1]

His wife, with whom he had three children, had died earlier, in 1912.[5]

Legacy

After Battey died, his negatives were packed up and put in storage under conditions that eventually destroyed them. As a result, Tuskegee Institute has only a few surviving prints from Battey's years of documentary work.[4]

In 1989, Battey's work was included in the exhibition "Black Photographers Bear Witness: 100 Years of Social Protest" at the Williams College Museum of Art.[8]

References

- Otfinoski, Steven. "Battey, C. M." African Americans in the Visual Arts. New York: Facts on File, 2003. ISBN 0816048800. 17–18. Google Books. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony, and Henry Louis Gates, eds. Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0195170555. 398. Google Books. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- Stauffer, John, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier. Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century's Most Photographed American. Liveright, 2015.

- Higgins, Chester. Preface to Some Time Ago: A Historical Portrait of Black Americas, 1850-1950. Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1980.

- Bieze, M. Booker T. Washington and the Art of Self-Representation. Vol. 50. Peter Lang, 2008, pp. 70–81.

- The original series appears to have envisioned John M. Langston and B. K. Bruce in place of Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. See Bieze (2008), pp. 73–74.

- "Photography and the African Diaspora". In Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture, vol 1. ABC-CLIO, 2008, p. 764.

- Grundberg, Andy. "Photography View: A Century of Black History Brought into Focus". New York Times, July 2, 1989.