Buth Diu

Buth Diu (d. c. 1972) was a politician who was one of the leaders of the Liberal Party in Sudan in the years before and after independence in 1956. His party represented the interests of the southerners. Although in favor of a federal system under which the south would have its own laws and administration, Buth Diu was not in favor of southern secession. As positions hardened during the drawn-out First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972) his compromise position was increasingly discredited.

Buth Diu | |

|---|---|

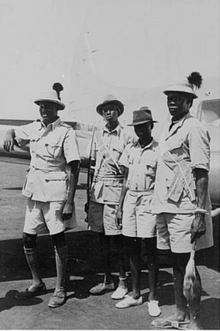

Four Nuer local government officials prior to a low-level flight over the central Nuer district in 1947, and including on the left Buth Diu, later one of the first southern members of the Legislative Assembly | |

| Born | |

| Died | c. 1972 |

| Nationality | Sudanese |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Known for | Early political leader from Southern Sudan |

Early years

Buth Diu belonged to the Nuer people.[1] He was born in Fangak in Southern Sudan. Buth Diu did not attend school, but managed to obtain a job as a houseboy of the British District Commissioner. He taught himself English and learned to read and write and type. With these skills, he became interpreter for the District Commissioner, an influential post.[2] By 1947 he was a local government official.[3]

Southern representative

After the Second World War the mood in Britain was to give the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan independence of both Britain and Egypt.[4] Buth Diu was one of the southern leaders who attended a conference held at Juba on 12–13 June 1947 to discuss the recommendations of an earlier conference held in Khartoum at which it had been decided that the south and north of Sudan should be united in one country. Southerners were (and are) very different ethnically and culturally from the people of northern Sudan, but the rationale was that Sudan was huge but poor, and if divided both parts would be extremely weak. No southerners had attended the Khartoum conference.[5]

At the Juba conference, Buth Diu said that although northerners claimed they did not want to dominate the South, there must be safeguards. Northerners should not be allowed to settle on land in the south without permission, should not interfere in local government in the south and should not be allowed in law to call a southerner a slave. However, Diu was not in favor of separation. He said the government should select representatives from the south who would go to the North to study and to participate in legislation, finance, and administration. He said that Arabic should be introduced into southern schools without delay so they could catch up to the north.[5]

Buth Diu formed an "Upper Nile Political Association" in Upper Nile province.[6] The Governor-General of Sudan announced the formation of the Constitution Amendment Commission in March 1951. Buth Diu was the sole southerner of the commission, which had 16 northerners and three British officials including the chairman.[4] When the commission started work on 26 March 1951, Buth Diu called for a federal constitution. His proposals were persistently rejected by the northern members of the commission, and he resigned in disgust. The commission continued without southern representation. However, the British members of the commission did insist on some safeguards in the draft constitution to protect southern interests, including a special Minister for the southern provinces and an Advisory Board for southern affairs. The northerners managed to later remove this provision.[7]

Party leader

The Southern Sudanese Political Movement was founded in 1951 by Stanislaus Paysama, Abdel Rahman Sule and Buth Diu.[8] As the Secretary General of the party, Buth Diu protested to the United Nations against the agreement that had been reached by the Constitution Amendment Commission.[9] In 1952 the party changed its name to the Southern Party. As of 1953 the party leaders were Benjamin Lwoki, Chairman, Stanslaus Paysama, Vice Chairman, Buth Diu, Secretary General and Abdel Rahman Sule, Patron of the party.[8] The objectives were to work for complete independence of Sudan, with special treatment for the south. The party was officially registered in 1953. At first it had widespread support from the southern intelligentsia and from the bulk of the people in the south of Sudan. In 1954 the party was renamed the Liberal Party to avoid any suspicion that it was working for independence of the south, but no northerners joined.[10]

Buth Diu toured the south in August 1954 at the expense of Sayyid 'Abd al-Rahman, patron of the Ummah Party, and in his speeches quoted the National Unionist Party (NUP) campaign promises. (The NUP had won the previous elections). Prime minister Ismael Azhari described this as seditious talk and threatened to use force to prevent secession.[11] Ismael Azhari eliminated Buth Diu and Bullen Alier from his cabinet for their criticism of the policy of his government on Southern Sudan.[12] The Sudanese parliament was dissolved in November 1958 after a military coup by General Ibrahim Abboud.[13]

Later years

In November 1964, General Ibrahim Abboud returned control to an interim civilian government. In 1965 a northern-dominated government was elected led by Muhammad Ahmad Mahgoub. This government paid lip service to a peaceful solution to the southern problem, while waging an increasingly brutal war against the Anyanya rebels. The Southern Front withdrew its candidates for the Supreme Council and the Cabinet, saying that the government had violated its agreement that the Southern Front would be the sole representative of the south. The Sudan African National Union (SANU) had two members appointed to the cabinet, Alfred Wol Akoc and Andrew Wieu, and Buth Diu was appointed to the third seat reserved for a southerner in the cabinet.[14] He was given the position of Minister of Animal Resources.[15] The two SANU ministers resigned in protest after the Juba and Wau massacres.[16] Buth Diu and Philimon Majok were now the only representatives of Southern Sudan in the government, both supporters of a unified Sudan.[14]

Buth Diu died soon after the 1972 Peace Accord was signed in Addis Ababa, ending the First Sudanese Civil War.[2] He had tried to bridge the huge gap between the south and the realities of northern politics, and often failed to satisfy either camp.[17] Buth Diu once said that Sudan was like an eagle with a broken wing, dragging itself along the ground, becoming weaker each day, longing to return to the freedom of the skies.[18]

References

- Lesch 1998, pp. 239.

- Everington 2007.

- Collins 2008, pp. 56.

- Akol Ruay 1994, pp. 61.

- Marwood 1947.

- Nyuot Yoh 2005, pp. 10.

- Akol Ruay 1994, pp. 66.

- Nyuot Yoh 2005, pp. 14-15.

- Nyuot Yoh 2005, pp. 13.

- Akol Ruay 1994, pp. 67.

- Daly 2003, pp. 383.

- Wai 1973, pp. 147.

- Harir, Tvedt & Badal 1994, pp. 105.

- Akol Ruay 1994, pp. 142.

- Eprile 1974, pp. 94.

- Collins 2006, pp. 91.

- Royal African Society 1985.

- Susser 2008, pp. 223,233.

Sources

- Akol Ruay, Deng D. (1994). The politics of two Sudans: the south and the north, 1821-1969. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 91-7106-344-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Robert O. (2006). The southern Sudan in historical perspective. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-4128-0585-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Robert O. (2008). A history of modern Sudan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-67495-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daly, M. W. (2003). Imperial Sudan: The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium 1934-1956. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53116-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eprile, Cecil (1974). War and peace in the Sudan, 1955-1972. David & Charles.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Everington, Peter (September 11, 2007). "The Sudanese and the British – Shared History". South Sudan Online. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved 2011-08-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harir, Sharif; Tvedt, Terje; Badal, Raphael K. (1994). Short-cut to decay: the case of the Sudan. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 91-7106-346-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lesch, Ann Mosely (1998). The Sudan: contested national identities. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21227-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marwood, B.V., GOVERNOR OF EQUATORIA (21 June 1947). "JUBA CONFERENCE 1947". Retrieved 2011-08-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nyuot Yoh, John G. (July 19 – August 28, 2005). "NOTES ON FOREIGN POLICY TRENDS OF SOUTHERN SUDAN POLITICAL AND MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS AND PARTIES (1940s-1972)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2012. Retrieved 2011-08-20.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Royal African Society (1985). African affairs, Volume 84, Issues 334-337. Oxford University Press. p. 141.

- Susser, Asher (2008). Challenges to the cohesion of the Arab state. The Moshe Dayan Center. ISBN 965-224-079-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wai, Dunstan M. (1973). The Southern Sudan: the problem of national integration. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-2985-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)