Burbank–Livingston–Griggs House

The Burbank–Livingston–Griggs House is the second-oldest house on Summit Avenue in Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. It was designed in Italianate style by architect Otis L. Wheelock of Chicago and built from 1862 to 1863. The work was commissioned by James C. Burbank, a wealthy owner of the Minnesota Stage Company.[2] Later, four significant local architects left their mark on the landmark structure.[3]

Burbank–Livingston–Griggs House | |

The Burbank–Livingston–Griggs House from the north | |

| |

| Location | 432 Summit Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota |

|---|---|

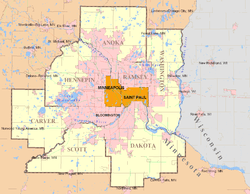

| Coordinates | 44°56′27″N 93°7′6″W |

| Built | 1862–63, 1925 |

| Built by | Otis L. Wheelock |

| Architectural style | Italianate |

| Part of | Historic Hill District (ID76001067) |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000307[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1970 |

The building was one of the first Minnesota properties nominated to the National Register of Historic Places, in 1970.[3] It was listed for its state-level significance in the theme of architecture.[4] It was nominated for being one of Minnesota's most elaborate examples of mid-19th-century Italianate architecture.[2] In 1976 it was also included as a contributing property to the Historic Hill District.[5]

Description

The Burbank–Livingston–Griggs House is built of grey limestone and features arched windows, a bracketed cornice with carved pendants, and a cupola topped with a finial.[3] Other architectural elements include polygonal bay windows and Corinthian order columns supporting an entablature.[6] The floor plan was open and spacious, with the first parquet floor in Minnesota as well as steam heat, hot and cold running water, and gas lighting. The rat-proof interior walls are lined with a layer of brick, providing an air chamber to insulate the house from the harsh winter cold.[3] Floors and staircases connecting the four levels are oak and marble.[6] A stairway leads to the glass-enclosed cupola on the roof. Servants, including three maids, a coachman, a driver, and a gardener, originally lived on the third floor.[3]

History

Summit Avenue was still only an oxcart trail when Wheelock arrived to build this Civil War-era mansion at the top of a steep hill. The picturesque country estate high on the Mississippi River bluff was constructed of massive blocks of limestone quarried across the river in Mendota, Minnesota.[3]

The site at 432 Summit Avenue overlooked the town, where owner James Crawford Burbank's steamboats and stagecoaches carried mail, passengers, and goods. Burbank had come to Saint Paul from Vermont in 1850 and built a financial empire from scratch, then reorganized the Saint Paul Fire & Marine Insurance Company and served as its president. He was active in civic affairs, founding the chamber of commerce, establishing Como Park, and constructing a streetcar system. He served in public office as a Ramsey County commissioner and state representative.[3]

In addition to Burbank, the house is named after two important owners who led the early growth and development of the capital city: Crawford Livingston and Theodore Wright Griggs. Mary Potts Livingston, the wife of Crawford Livingston, was a niece of Henry Hastings Sibley, Minnesota's first governor.[3]

In 1884, 20 years after the house was built, the Livingston family worked with architect Clarence H. Johnston Sr. to replace the single window on the stairs with three arched windows of stained glass and install elaborately carved oak paneling in the entry. After those improvements, the home was relatively unchanged for many years.[3]

Mary Livingston Griggs inherited the house from her parents in 1925. She worked with architect Allen H. Stem to expand the living space with a two-story limestone addition and remodel the living room in the style of a 17th-century English Renaissance chamber. Her love for history and antiques inspired her to install whole rooms brought over from elegant French and Italian houses in Europe and furnished with antiques from the period.[3]

When Stem retired from his architectural practice, Magnus Jemne began installing late-18th-century French panels in the grand salon and bedroom suite. Edwin Hugh Lundie completed the complicated task of fitting the antique interiors in the dining room, two bedrooms, two sitting rooms, wardrobe rooms, and a small hallway. In the basement, he designed a glass-walled ballroom in the latest Art Deco style for the Griggs' children.[3]

In 1968, Mary Griggs' daughter Mary Griggs Burke donated the house to the Minnesota Historical Society and the Saint Paul Junior League, which operated a house museum for many years with the assistance of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.[3]

In 1996, the Burbank–Livingston–Griggs House was sold and turned into three separate furnished apartments, once again becoming a residence.[3]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burbank–Livingston–Griggs House. |

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Grossman, John (1970-04-10). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Burbank - Livingston - Griggs House". National Park Service. Retrieved 2018-09-03. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) With one undated accompanying photo - Mathison, Joan (2018-03-28). "Burbank-Livingston-Griggs House, St. Paul". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- "Burbank-Livingston-Griggs House". Minnesota National Register Properties Database. Minnesota Historical Society. 2009. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- Nelson, Charles W.; Susan Zeik (1976-06-07). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Historic Hill District". National Park Service. Retrieved 2018-09-03. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Silverman, Eleni. "James C. Burbank House". Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. Retrieved 2007-12-13.