Bud Fowler

John W. "Bud" Fowler (March 16, 1858 – February 26, 1913) was an American baseball player, manager, and club organizer. He is the earliest known African-American player in organized professional baseball; that is, the major leagues and minor leagues.

| Bud Fowler | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| P / C / IF / OF / Manager | |||

| Born: March 16, 1858 Fort Plain, New York | |||

| Died: February 26, 1913 (aged 54) Frankfort, New York | |||

| |||

| Negro leagues debut | |||

| 1895, for the Page Fence Giants | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| 1898, for the Cuban Giants | |||

Early life

The son of a fugitive hop-picker and barber, Bud Fowler was christened John W. Jackson.[1] His father had escaped from slavery and migrated to New York. In 1859, his family moved from Fort Plain, New York, to Cooperstown. He learned to play baseball during his youth in Cooperstown. It is unknown why he adopted the name "Bud Fowler", although biographer L. Robert Davids claims he was nicknamed "Bud" because he called the other players by that name.

Professional baseball career

Early career

Fowler first played for an all-white professional team based out of New Castle, Pennsylvania in 1872, when he was 14 years old.[2] He is documented as playing for another professional team on July 21, 1877, when he was 19.[3] On April 24, 1878, he pitched a game for the Picked Nine, who defeated the Boston Red Caps, champions of the National League in 1877.[4] He pitched some more for the Chelsea team, then finished that season with the Worcester club.

Largely supporting himself as a barber, Fowler continued to play for baseball teams in New England and Canada for the next four years. He then moved to the Midwest. In 1883, Fowler played for a team in Niles, Ohio; in 1884, he played for Stillwater, Minnesota, in the Northwestern League.

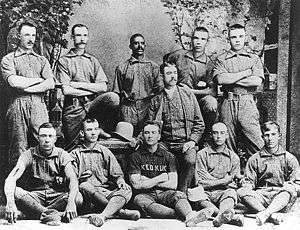

Keokuk

Keokuk, Iowa had not had a professional baseball team since 1875. However, in 1885, local businessman R. W. "Nick" Curtis was the chief force behind starting a new team and hired Fowler for it. Johnny Peters, the manager of the then-disbanded Stillwater, Minnesota team, helped Fowler get connected with the new team in Keokuk, the Keokuk Hawkeyes.

Fowler became the most popular player on the Keokuk team. The local newspaper, the Keokuk Gate City and Constitution, described him as "a good ball player, a hard worker, a genius on the ball field, intelligent, gentlemanly in his conduct and deserving of the good opinion entertained for him by base ball admirers here." Fowler also commented to the local newspaper on issues with the "reserve clause," the contractual mechanism that allowed teams to hold on to players for their entire career. Fowler stated that "when a ball player signs a league contract they can do anything with him under its provisions but hang him."[5]

The Western League folded that season due to financial reasons, leaving Keokuk without a league, and Fowler was released.

Later career

Fowler moved to play with a team in Pueblo, Colorado. In 1886, he played for a team in Topeka, Kansas. That team won the pennant behind Fowler's .309 average. He also led the league in triples. In 1887, Fowler moved to Binghamton, New York and played on a team there. Racial tensions arose, and his teammates refused to continue playing with him. In 1888, he played for a team in Terre Haute, Indiana. In 1892, Fowler played for Kearney, Nebraska in the Nebraska State League.

In 1895, Fowler and Home Run Johnson formed the Page Fence Giants in Adrian, Michigan.[6] From 1894 to 1904, Fowler played and/or managed the Page Fence Giants,[7] Cuban Giants, Smoky City Giants, All-American Black Tourists, and Kansas City Stars.

According to baseball historian James A. Riley, Fowler played 10 seasons of organized baseball, "a record [for an African American player] until broken by Jackie Robinson in his last season with the Brooklyn Dodgers."[1]

Later life and legacy

Fowler died in Frankfort, New York, on February 26, 1913. In his last years, he suffered from illness and poverty which was covered by national media. His grave was unmarked.

In 1987, the Society for American Baseball Research placed a memorial on his grave to memorialize and honor his successes as the first professional African-American baseball player.[5] Cooperstown, New York, declared April 20, 2013 as "Bud Fowler Day," dedicating a plaque and presenting an exhibit in his honor at Doubleday Field (it was prepared by The Cooperstown Graduate Program). The street leading to the Field has been named "Fowler Way."[8] On July 29, 2020, the Society for American Baseball Research announced that Bud Fowler was selected as SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legend of 2020 — a 19th-century player, manager, executive or other baseball personality not yet inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

See also

References

- Riley, James A. (1994). "Fowler, John W. (Bud)". The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. Carroll & Graf. pp. 294–95. ISBN 0-7867-0959-6.

- Rader, Benjamin G. (2008). Baseball : a history of America's game (3rd ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03302-5.

- Queen, Frank, ed. (21 July 1877). "Our Boys vs. Franklin" (PDF). New York Clipper. 25 (17). New York City, NY. p. 131. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- Queen, Frank, ed. (4 May 1878). "Boston vs. Picked Nine" (PDF). New York Clipper. 26 (6). New York City, NY. p. 45. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- Christian, Ralph J. (2006). "Bud Fowler: The First African American Professional Baseball Player and the 1885 Keokuks". Iowa Heritage Illustrated 87(1): 28-32.

- "Page Fence Giants". Baseball History Daily. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Pounded at 'Haha' ", Minneapolis Journal, Minneapolis, MN, April 22, 1895, Page 6, Column 3

- "Acclaim Comes Late for Baseball Pioneer", New York Times

Further reading

- Davids, L. Robert (1989). "John Fowler (Bud)". Nineteenth Century Stars. Edited by Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker. Kansas City, MO: SABR. ISBN 0-910137-35-8

- Laing, Jeff. (2013). Bud Fowler: Baseball's First Black Professional. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7264-2

External links

- Career minor league stats at Baseball Reference

- Biography at Society for American Baseball Research

- (Riley.) John "Bud" Fowler, Personal profiles at Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. – identical to Riley (confirmed 2010-04-13)

- "Belated honors for pioneering black ballplayer Bud Fowler," by JIM ANDERSON, Minneapolis Star Tribune, February 27, 2013

- "Bud Fowler Selected as SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legend of 2020"