Bud, Not Buddy

Bud, Not Buddy is the second children's novel written by Christopher Paul Curtis. The first book to receive both the Newbery Medal for excellence in American children's literature, and the Coretta Scott King Award, which is given to outstanding African-American authors, Bud, Not Buddy was also recognized with the William Allen White Children's Book Award for grades 6-8.[1][2][3][4][5]

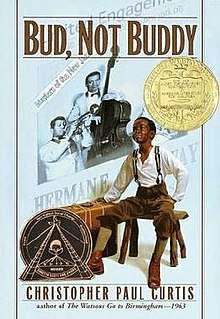

Front cover of Bud, Not Buddy. | |

| Author | Christopher Paul Curtis |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Adult humor, Multicultural fiction, Historical fiction, Children's literature |

| Publisher | Delacorte Books for Adult Readers |

Publication date | 1999 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 245 pages |

| ISBN | 0-385-32306-9 |

| OCLC | 40744296 |

| LC Class | PZ7.C94137 Bu 1999 |

Setting and historic significance

The novel is set in Michigan, the home state of the author. This is also the setting of his first novel, The Watsons Go to Birmingham.[6] Bud, the main character, travels from Flint to Grand Rapids, giving readers a glimpse of the midwestern state in the late 1930's; he meets a homeless family and a labor organizer and experiences life as an orphaned youth and the racism of the time, such as laws that prohibited African Americans from owning land in many areas, the dangers facing blacks, and racial segregation.[7]

One element of the historic setting is a Sundown town, where racist covenants prohibit African Americans from living and custom endangers the lives of any found there after dark. Bud meets Lefty, a well-meaning passer-by who becomes a good friend when he cautions Bud to keep him from entering a Sundown town. The character of Lefty, a ball player, was based on one of the author's grandfathers.[1][8]

The effects of The Depression on this area are described throughout the story of Bud's journey across the state. Bud spends an evening in Flint's Hooverville, a hobo encampment, where he comments on the mixture of races; the author points to the police presence and the tension between police and those attempting to hop trains,[1][8] their poverty and desperate migration characterizing the Great Depression.[9] The uncertainty of the era is reflected in Bud's own life, as his transience and loss of home were experienced by many migrant families and orphaned children.[10]

Jazz music and musicians are a central part of the narrative; the author was inspired to create the story by his own grandfather, who was a jazz musician during The Depression. The band Bud searches for is named for a band that the author's other grandfather played with, called Herman Curtis and the Dusky Devastators of The Depression. Bud connects to his new friends and family through the music, which is a part of his history as an African American and exemplifies the popular music of the era.[1][6][11]

Plot

The story opens with Bud being placed with a new foster family, the Amoses'. Bud soon meets Todd Amos, their 12-year-old son, who teases him mercilessly and calls him Buddy. After a fight with Todd, Bud is forced to spend the night in the garden shed. In the shed, he mistakes a hornet nest for a vampire bat and hits the nest with a rake. This upsets the hornets and Bud gets stung. During his adrenaline rush, he breaks through the window of the shed.

After escaping the shed, Bud takes revenge on Todd by making him wet his bed by pouring warm water on Todd. He escapes and sleeps under a Christmas tree for the night. His friend Bugs wakes him up so they can go to the West.

Bud runs away with Bugs. They try to hop on a train, but Bud fails to make it and is left behind. Bud starts walking to Grand Rapids, Michigan. On the way, he meets Lefty Lewis, who gives him a ride in his car to Grand Rapids to find his father, who he believes is Herman E. Calloway. He stays with Lefty for a short while, then leaves to find his father.

Bud meets Herman and his band and declares himself to be Herman's son, though his confidence is shaken when he sees that Herman is elderly. The band treats Bud with kindness, but Herman treats Bud with great animosity. Bud delivers the news that his mom, Angela, is dead. This brings great grief to Herman, who is revealed to in fact be Bud's grandfather and Angela's estranged father.

The story ends with Bud becoming friends with the band members and receives a horn. Herman apologizes to Bud for his animosity and allows him to stay with him and the band. Despite all of his dilemmas and all of his grief, Bud may finally have a happy ending.

Reception and analysis

Curtis' novel was received well and referenced as a children’s fiction source for learning about the Depression era and Jazz, as well as social issues like violence and racism. Points of discussion have focused on parallels between Bud's journey to find his father, and the common experience of many people during the Great Depression as they had to move around looking for work and new homes.[10] The child narrator and historic context have made Curtis’ book a choice for teachers, the audiobook has also been used as part of teaching curriculums.[12][13]

The novel was praised for its historical context as well as its humorous narrator.[7] Bud has various rules to live by called, “Bud Caldwell’s Rules and Things for Having a Funner Life and Making a Better Liar Our of Yourself.”[9][14] Throughout his story, these rules are part of the humor and cleverness expressed by the main character as he encounters different people and situations.[1][14]

Bud’s innocence as a young narrator is repeatedly cited by reviewers and academics studying how Bud experiences, but does not deeply examine, world issues as a child.[6][1] His belief in vampires and other supernatural ideas are also used as discussion point by educators. The simple ways Curtis has Bud describe forms of racism are quoted and highlighted. He is mistreated or helped by other characters in the novel; the former actions coming from his foster family and the latter coming from the friends he makes on the road. Bud's insistence on being addressed by his name and not some alternative nickname is also looked at closely when analyzing the impact of the main character and his personal strength.[8] These are all elements that have been analyzed in academic writing, reviewed and used in classrooms for teaching history, and social justice issues.[6][1][14][15]

The Jazz music in the novel is also used as a point of entry for connecting to the story and for expanding on the learning experience, by adding an audio element to the novel. This is noted as a way to recommend students who might be music fans to the story.[12] Jazz music is part of the audio book and discussed as a learning tool on educators resource sites; students who might not have heard Jazz are introduced through the audio books inclusion of Jazz at the end of chapters.[1][13]

Stage adaptation

Bud, Not Buddy was adapted for the stage by Reginald Andre Jackson[16] for Black History Month, in Fremont, California. The production premiered in 2006 at the Langston Hughes Cultural Arts Center. It has been produced several times, including at the Children's Theatre Company in Minneapolis, Main Street Theatre in Houston, the University of Michigan-Flint and Children's Theatre of Charlotte. Jackson's adaptation was published by Dramatic Publishing in 2009, it won the Distinguished Play Award (Adaptation) from The American Alliance for Theatre and Education in 2010.[16]

In January 2017, an adaptation of the novel premiered at Eisenhower Theater in The Kennedy Center for Performing Arts; it was a blend of Jazz concert and theater. The music was composed by Terence Blanchard and the script was written by Kirsten Greenidge. Actors and musicians shared the stage instead of being separated by a stage and orchestra pit. The adaptation added live music written specifically to highlight the Jazz world in Michigan where Bud went to find the musician he thought was his father. The score was composed to be played by high school bands in future productions, and it was written to be a challenging score for students.[17][18]

Awards

Bud, Not Buddy received the 2000 Newbery Medal for excellence in American children's literature, over twenty years after the first African American author had received the honor.[11] Christopher Paul Curtis was also recognized with the 2000 Coretta Scott King Award, an award given to outstanding African-American authors. These national honors were given in addition to fourteen different state awards.[2][19]

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Holes |

Newbery Medal recipient 2000 |

Succeeded by A Year Down Yonder |

| Preceded by Heaven |

Coretta Scott King Author Award 2000 |

Succeeded by Miracle's Boys |

| Preceded by Holes |

Winner of the William Allen White Children's Book Award Grades 6–8 2002 |

Succeeded by Dovey Coe |

| Bud, Not Buddy Awards | |

|---|---|

| 1999 | Best Book of the Year by School Library Journal |

| 1999 | Best Book of the Year by Publishers Weekly Notable |

| 1999 | Notable Book of the Year by New York Times |

| 1999 | Parents Choice Award |

| 2000 | Blackboard Book of the Year |

| 2000 | Newbery Medal for the Most Distinguished Contribution to American Literature for Children |

| 2000 | Coretta Scott King Award |

| 2000 | International Reading Associations Children's and Young Adults Book Awards |

| 2002 | William Allen White Children's Book Award (Grades 6-8) |

| 2002 | NCSS-CBC Notable Children's Trade Book in Social Studies |

References

- Cart, Michael (February 15, 2000). "On the Road with Bud (not Buddy). Booklist 96(12)". link.galegroup.com. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis: 9780440413288 | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- Newbery Medal and Honor Books, 1922-Present, American Library Association, retrieved 2012-11-14

- Coretta Scott King Book Award Complete List of Recipients—by Year Archived November 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, American Library Association, retrieved 2012-11-14

- "Winner 2001-2002 - William Allen White Children's Book Awards | Emporia State University". emporia.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-10-13. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- Barker, J. "Naive narrators and double narratives of racially motivated violence in the historical fiction of Christopher Paul Curtis. Children's Literature, 41, 172-203,309". ProQuest 1399544033. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Metzger, Lois (1999-11-21). "CHILDREN'S BOOKS; On Their Own". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-11-28.

- Land, Mary Camille (Spring 2015). "Retelling a Traditional Narrative in Christopher Paul Curtis' Bud, Not Buddy" (PDF). University of West Georgia.

- Kastor, Elizabeth (June 26, 2002). "Rules to live by: On the road with 'Bud, Not Buddy'". ProQuest 2076075485. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Greathouse, Paula; Kaywell, Joan F.; Eisenbach, Brooke (2017-10-05). Adolescent Literature as a Complement to the Content Areas: Social Science and the Humanities. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4758-3832-9.

- Robotham, Rosemarie. "Bud, Not Buddy". link.galegroup.com. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- Burner, Joyce Adams (April 1, 2009). "Jazz: Dig It! | Focus On". School Library Journal. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Kaiser, Marjorie M. (2000). "Non-Print YA Literature Connection- Bud, Not Buddy: Common Reading, Uncommon Listening". The ALAN Review. 27 (3). doi:10.21061/alan.v27i3.a.8. ISSN 0882-2840.

- Hurst, Carol. "Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis". carolhurst.com. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Knieling, Matthew. ""An Offense to Their Human Rights": Connecting Bud, not Buddy to the Flint Water Crisis with Middle School ELA Students". offcampus.lib.washington.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "Reginald Andre Jackson". freeholdtheatre.org. Seattle: Freehold Theatre. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- Mostafavi, Kendall (2017-01-14). "Review: 'Bud, Not Buddy' at The Kennedy Center". DC Metro Theater Arts. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "Jazzman Terence Blanchard brings swing to 'Bud, Not Buddy'". Washingtonpost.com. 2017-01-12. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "Awards for Christopher Paul Curtis". fictiondb.com. Retrieved 2019-11-27.