Britannia-class steamship

The Britannia-class was the Cunard Line's initial fleet of wooden paddlers that established the first year round scheduled Atlantic steamship service in 1840. By 1845, steamships carried half of the transatlantic saloon passengers and Cunard dominated this trade. While the units of the Britannia class were solid performers, they were not superior to many of the other steamers being placed on the Atlantic at that time. What made the Britannia-class successful is that it was the first homogeneous class of transatlantic steamships to provide a frequent and uniform service. Britannia, Acadia and Caledonia were commissioned in 1840 and Columbia in 1841 enabling Cunard to provide the dependable schedule of sailings required under his mail contracts with the Admiralty. It was these mail contracts that enabled Cunard to survive when all of his early competitors failed.[1]

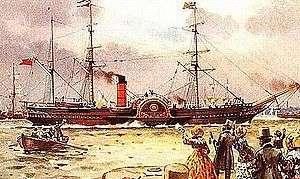

Britannia of 1840, the first Cunard liner built for the transatlantic | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders: | Robert Duncan & Co., John & Charles Wood, Robert Steele & Co. |

| Operators: | Cunard Line |

| Succeeded by: | America Class |

| Subclasses: | Hibernia Class |

| Built: | 1840–1845 |

| Completed: | 6 |

| Lost: | 3 |

| General characteristics : Britanna, Acadia,Caledonia & Columbia | |

| Tonnage: | 1150 GRT |

| Length: | 207 ft (63 m) |

| Beam: | 34 ft (10 m) |

| Propulsion: | Robert Napier and Sons two-cylinder side-lever steam engine, 740 indicated horsepower, paddle wheels |

| Speed: | 9 knots (17 km/h; 10 mph) |

| General characteristics : Hibernia & Cambria | |

| Tonnage: | 1400 GRT |

| Length: | 219 ft (67 m) |

| Beam: | 35 ft (11 m) |

| Propulsion: | Napier two-cylinder side-lever steam engine, 1040 indicated horsepower, paddle wheels |

| Speed: | 9.5 knots (17.6 km/h; 10.9 mph) |

Cunard’s ships were reduced versions of Great Western and only carried 115 passengers in conditions that Charles Dickens unfavorably likened to a "gigantic hearse". Mean 1840 – 1841 Liverpool - Halifax times for the quartette were 13 days, 6 hours (7.9 knots) westbound and 11 days, 3 hours (9.3 knots) eastbound. The initial four units were insufficient to meet the contracted sailings, and an enhanced unit, the Hibernia was commissioned in 1843. When Columbia was wrecked in 1843 without loss of life, Cambria was ordered to replace her.[2]

In 1849 and 1850, the surviving original units along with Hibernia were sold to foreign navies after completing forty round trips for Cunard. Cambria remained in the Cunard fleet for another decade.[2]

Development and design

In his initial negotiations with Admiral Parry, Samuel Cunard contemplated a fortnightly service from Liverpool to Halifax and onto Boston using three 800 GRT steamers. This was 40% smaller than Great Western, which had just entered service from Bristol to New York. When completed, the Cunard’s ships grew to 1150 GRT but were still 15% smaller than Great Western. The other steamships under construction for Atlantic service at the time were also bigger than Cunard’s initial units. Cunard’s final contract added a fourth unit to insure that the fortnightly schedule could be maintained ten months a year with sailings during the height of winter reduced to monthly.[2]

Samuel Cunard's major backer was Robert Napier, whose Robert Napier and Sons was the Royal Navy's supplier of steam engines. For the Britannia-class, Napier designed a two-cylinder side lever engine that produced 740 indicated horsepower, just ten horsepower less than Great Western. Unlike most other Atlantic steamers, Britannia’s boilers were located aft of her engines and paddle wheels, resulting in a unique profile. The ships had three masts and full rigging for sails. To speed delivery, construction of the wooden hulls was contracted to three Clyde ship yards.[1]

Cunard’s major concern was the delivery of the mail and most of the ship’s space was allocated to engines and coal. The Britannia quartette also carried 115 passengers traveling in a single class along with 225 tons of cargo. The dining room was a long deck house aft of the funnel and the only other public room was a small ladies cabin. A special padded deck house had the ship’s cow and overturned boats protected vegetables from the weather. Smoking was limited to the upper deck.[2]

Charles Dickens and his wife crossed from Liverpool to Boston during a January 1842 storm. He wrote:

"Before descending into the bowels of the ship, we had passed from the deck into a long narrow apartment, not unlike a gigantic hearse with windows in the sides; having at the upper end a melancholy stove at which three or four chilly stewards were warming their hands; while on either side, extending down its whole dreary length, was a long, long table over which a rack, fixed to the low roof and stuck full of drinking-glasses and cruet-stands, hinted dismally at rolling seas and heavy weather."[2]

Describing the cabin, Dickens wrote:

"..deducting the two berths, one above the other (the top one a most inaccessible shelf) than which nothing smaller for sleeping in was ever made except coffins, it was no bigger than one of those hackney cabriolets which have the door behind and soot their fares out, like sacks of coals, upon the pavement."[2]

While Britannia and her sisters had a favorable power-to-weight ratio, they were only able to match Great Western’s speed. Britannia took the eastbound record from Great Western in August 1840, but Great Western regained it in April 1842. Columbia took the westbound Blue Riband from Great Western in April 1841 before losing it again to Great Western in 1843. Columbia also took the eastbound record in April 1843 before she was wrecked.

Cunard quickly realized that five units were required to maintain the fortnightly service and in 1843 he commissioned an enhanced Britannia with 300 additional horsepower. While 21% larger than the original Britannia, Hibernia only carried 5 more passengers. Hibernia immediately took the eastbound record from Columbia and held it until 1849. When Columbia was lost in 1843, a second enhanced unit, Cambria was ordered as her replacement. Cambria took the westbound Blue Riband when she entered service in 1845 and held the honor until 1848.[2]

Service histories

Britannia

In March 1849 Britannia was sold to the German Confederation Navy and renamed SMS Barbarossa. Fitted with nine guns, she served as the flagship of the Reichsflotte under Karl Rudolf Brommy in the Battle of Heligoland. In June 1852 she was transferred to the Prussian Navy and used as a barracks ship at Danzig. Twenty eight years later, she was decommissioned and in July 1880 she was sunk as a target ship.[1]

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Great Western |

Blue Riband (Eastbound record) 1840 - 1842 |

Succeeded by Great Western |

Acadia

Acadia had a reputation for speed, but never actually won a speed record. She was also sold in 1849 to the North German Confederation Navy for conversion to the frigate, Ersherzog Johann. When that navy was dissolved, Ersherzog Johann was sold to W. A. Fritze and Company of Bremen, Germany’s first oceangoing steamship venture. The former Acadia was converted back to an Atlantic liner and renamed Germania. In August 1853, she took the new line’s initial sailing, but required 24 days to reach New York because of boiler problems. Sailings were erratic until the fleet was chartered for trooping during the Crimean War. Germania was out of service after the war until she was sold to British ship-owners. Her final deployment was as a troopship during the Indian Mutiny before she was scrapped in 1858.[2]

Caledonia

Caledonia was sold to the Spanish Navy in 1850 and was lost outside Havana the next year.[2]

Columbia

Columbia was also known as a fast ship and held the Blue Riband for two years. On July 2, 1843, she was wrecked on Devil's Limb Reef at Seal Island, Nova Scotia, without loss of life.[1]

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Great Western |

Holder of the Blue Riband (Westbound record) 1841 - 1843 |

Succeeded by Great Western |

| Blue Riband (Eastbound Record) 1843 |

Succeeded by Hibernia | |

Hibernia

Hibernia took the first sailing to New York when Cunard added that city to the schedule in 1848. She was also sold to the Spanish Navy in 1850 and converted to the frigate Habanois. The former Cunarder was lost in 1868.[2]

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Columbia |

Blue Riband (Eastbound Record) 1843 - 1849 |

Succeeded by Canada |

Cambria

Cambria was the replacement for the wrecked Columbia. She held the Blue Riband for the fastest westbound Atlantic voyage from July 1845 until America won the record in June 1848. Cambria grounded on Cape Cod in April 1846, but was towed off. She was to be replaced by Arabia in 1852, but was retained when Arabia’s sister was sold before completion. After serving as a trooper in the Crimean War, Cambria was briefly placed back on the Boston service until Persia was commissioned. Cambria went into reserve except for charter to the European and Australian Royal Mail Company. In 1860, Cambria was sold to Italian owners and served in the Italian Navy until scrapped in 1875.[1]

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Great Western |

Holder of the Blue Riband (Westbound record) 1845 - 1848 |

Succeeded by America |

References

- Kludas, Arnold (1999). Record breakers of the North Atlantic, Blue Riband Liners 1838-1953. London: Chatham.

- Gibbs, Charles Robert Vernon (1957). Passenger Liners of the Western Ocean: A Record of Atlantic Steam and Motor Passenger Vessels from 1838 to the Present Day. John De Graff.