Snaffle bit

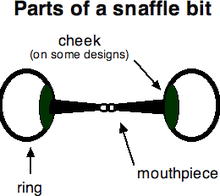

A snaffle bit is the most common type of bit used while riding horses. It consists of a bit mouthpiece with a ring on either side and acts with direct pressure. A bridle utilizing only a snaffle bit is often called a "snaffle bridle", particularly in the English riding disciplines. A bridle that carries two bits, a curb bit and a snaffle, or "bradoon", is called a double bridle.

A snaffle is not necessarily a bit with a jointed bit mouthpiece, as is often thought. A bit is a snaffle because it creates direct pressure without leverage on the mouth. It is a bit without a shank. Therefore, a single- or double-jointed mouthpiece, though the most common designs for snaffle bits, does not make a bit a snaffle. Even a mullen mouth (a solid, slightly curved bar) or a bar bit is a snaffle.

Action

The snaffle bit works on several parts of the horse's mouth; the mouthpiece of the bit acts on the tongue and bars, the lips of the horse also feel pressure from both the mouthpiece and the rings. The rings also serve to act on the side of the mouth, and, depending on design, the sides of the jawbone.[1]

A snaffle is sometimes mistakenly thought of as "any mild bit". While direct pressure without leverage is milder than pressure with leverage, nonetheless, certain types of snaffle bits can be extremely harsh when manufactured with wire, twisted metal or other "sharp" elements. A thin or rough-surfaced snaffle, used harshly, can damage a horse's mouth.[2]

Curb chains or straps have no effect on a true snaffle because there is no leverage to act upon. English riders do not add any type of curb strap or curb chain to a snaffle bit. While some riders in western disciplines do add a curb strap to the rings, it is merely a "hobble" for the rings, has no leverage effect and is there only as a safety feature to prevent the rings from being pulled through the mouth of the horse, should the animal gape open its mouth in an attempt to avoid the bit, an outcome prevented in an English bridle by the presence of a cavesson noseband.

Difference from a curb

The snaffle differs from the pelham bit, the curb bit, and the kimberwicke in that it is a non-leverage bit, and so does not amplify the pressure applied by the reins. With a snaffle, one ounce of pressure applied by the reins to a snaffle mouthpiece will apply one ounce of pressure on the mouth. With a curb, one ounce of pressure on the reins will apply more – sometimes far more – than one ounce of pressure on the horse's mouth.[2]

There are many riders (and a remarkable number of tack shops) who do not know the true definition of a snaffle: a bit that is non-leverage. This often results in a rider purchasing a jointed mouthpiece bit with shanks, because it is labeled a "snaffle," and believing that it is soft and kind because of the connotation the snaffle name has with being mild. In truth, the rider actually bought a curb bit with a jointed mouthpiece, which actually is a fairly severe bit due to the combination of a nutcracker effect on the jaw and leverage from the shanks.

A true snaffle does not have a shank like a pelham or curb bit. Although the kimberwicke appears to have a D-shaped bit ring like a snaffle, the bit mouthpiece is not centered on the ring, and thus applying the reins creates leverage; in the Uxeter kimberwicke, there are slots for the reins placed within the bit ring, which allows the reins to create additional leverage. Both are used with a curb chain, thus the ring acts like a bit shank and creates a slight amount of leverage, making it a type of curb bit.

A true snaffle also will not be able to slide up and down the rings of the bit or cheekpieces of the bridle, as this would place it in the gag bit category.

The mouthpiece

The mouthpiece is the more important part of a snaffle, as it controls the severity of the bit. Thinner mouthpieces are more severe, as are those that are rougher.

- Jointed mouthpiece: applies pressure to the tongue, lips, and bars with a "nutcracker" action. This is the most common mouthpiece found on a snaffle.[3]

- Mullen mouth: made of hard rubber or a half-moon of metal, it places even pressure on the mouthpiece, lips, and bars. It is a very mild mouthpiece.[3]

- French mouth: a double-jointed mouthpiece with a bone-shaped link in the middle. It reduces the nutcracker action and encourages the horse to relax. Very mild.

- Dr. Bristol: a double-jointed mouthpiece with a thin rectangular link in the middle that is set at an angle, creating a pressure point. It is a fairly severe bit. The French link is similar but much gentler because the link in the middle is flat against the tongue, lips, and bar and has no pressure points. Neither the Dr. Bristol nor the French Link nutcracker, but their severity is totally opposite.

- Slow twist: a single-jointed mouthpiece with a slight twist in it. Stronger and more severe.

- Corkscrew: Many small edges amplifies the pressure on the mouth. Severe.

- Single- and double-twisted wire: two of the most severe mouthpieces, as they are not only thin, but they also have a "nutcracker" action from the single joint and the mouthpiece concentrates pressure due to its severe twisting.[4]

- Roller mouthpieces: tend to make horses relax their mouth and activate the tongue, encouraging salivation and acceptance of the bit. This may also focus tense or nervous horses to the bit.[4]

- Hollow mouth: usually single-jointed with a thick, hollow mouthpiece which spreads out the pressure and makes the bit less severe. May not fit comfortably in some horses' mouths if they are a little small.

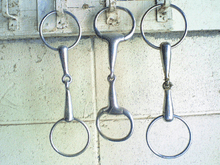

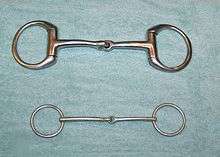

The snaffle rings

There are several types of rings that affect the action of the bit.

- Loose ring: slides through the mouthpiece. Tends to make the horse relax his jaw and chew the bit. May pinch the corners of the horse's mouth if the holes in the mouthpiece are large, in which case a bit guard should be used.[5]

- Egg butt/barrel head: mouthpiece does not rotate, and is so more fixed in the horse's mouth, which some horses prefer. Will not pinch the lips.[6][7]

- Dee-ring/ racing snaffle: ring in the shape of a "D" which does not allow the bit to rotate and so the bit is more fixed. The sides of the D provide a lateral guiding effect.[6]

- Full cheek: has long, extended arms above and below the mouthpiece on either side of the lips of the horse, with a ring attached to it. The cheeks have a lateral guiding effect, and also prevent the bit from sliding through the mouth. The full cheek is often used with bit keepers to prevent the cheeks from getting caught on anything, and to keep the bit in the right position inside the mouth.[5][6]

- Half-cheek: has only an upper or, more commonly, lower cheek, as opposed to both seen in a full cheek snaffle. Often used in racing, as there is less chance of the cheek being caught on the starting gate, or in driving as there is less chance of getting caught on harness straps.

- Baucher (hanging cheek): has a ring on the side of the mouthpiece, with a smaller ring above to attach the cheekpiece of the bridle. Tends to concentrate pressure on the bars. It is very fixed in the mouth.

- Fulmer: a full cheek bit with a loose ring attached, so that it not only has the lateral guiding effect, but can also move freely as with a loose ring.[6]

Fitting

The most important thing to remember when fitting a bit is that no two horses are completely alike. What is preferred by one, may cause severe problems in another. It is therefore the rider's duty to find a bit that not only suits the horse (both mouthpiece and ring), but one that fits correctly. The three main criteria in fitting the snaffle are the height the bit is raised in the mouth (adjusted by the cheekpieces), the width of the bit (from where the mouthpiece hits one ring, to where it hits the other), and the thickness of the mouthpiece.

Height

Theories as to fitting the snaffle vary between horse owners, but the most common theory of fitting the snaffle is to adjust it so that it creates one or two wrinkles in the lips at the corner of the horse's mouth. The best way to determine how high a snaffle should be is to begin with the bit just touching the corners of the horse's mouth, forming one wrinkle. If the rider holds the cheekpieces of the bridle and moves them up, there should remain enough give in the bridle to raise the bit in the horses mouth, however, there should not be excessive slack in the cheekpieces when this is done.

The horse should keep its mouth closed over a properly-fitted bit (slight chewing is acceptable and a sign of relaxation) and hold its head quietly. A bit may need to be adjusted either higher or lower until the horse shows no signs of discomfort. The height of the bit in the horse's mouth has little significant impact on its severity. Some riders mistakenly think that raising or lowering the bit increases its effect, but this is not correct. The bit is most effective when properly adjusted. Improper adjustment only causes discomfort, not increased control.

Factors that affect the fit of the bit include both the length of the mouth overall, the length of the interdental space between the incisors and the molars where the bit rests on the bars (gums) of the horse's mouth, the thickness of the horse's tongue and the height of the mouth from tongue to palate. There is less room for error with a horse who has a short mouth, thick tongue and a low palate than with a horse who has a longer mouth, thinner tongue and a higher palate.

One of the important criteria when fitting the snaffle is that it does not hit the horse's teeth. The greater concern is that the bit not be so high as to constantly rub on the molars, which can cause considerable discomfort to the horse. A bit adjusted too low usually will not come anywhere near the incisors, even on a short-mouthed horse, until the entire bridle is at risk of falling off.

If the bit is adjusted too low (not touching the corner of the mouth), it is primarily a safety concern, though the action of the bit can also be altered and lead to discomfort. A horse can get its tongue over a too-low bit and thus evade its pressure, plus the action of the bit is altered and it will not act on the mouth as it was designed. Horses with a bit too low will often open their mouths to evade pressure and may chew on it excessively. In extreme cases, the bridle could even fall off if the rider pulls hard on the reins, hence raising the bit and loosening the cheekpieces, at the same time the horse rubs, tosses or shakes its head vigorously.

Many horses will "carry" a too-low bit themselves, using their tongue to hold it in the proper place. Some trainers, especially in western riding disciplines, consider this desirable and adjust a bridle a bit low to encourage this behavior. Other trainers, especially in English riding disciplines, prefer to hang the bit a little higher so it is in the correct position without need for the horse to move it there.

If the bit is too high (depending on the horse, at three or more wrinkles in the lips), it will irritate the lips, leading to callousing and a loss of sensitivity over time. However, the more immediate consequence is that the horse feels constant bit pressure and cannot get any release, even if the rider loosens the reins. This leads to the horse becoming tense in the jaw and resisting the bit. Most of all, if a too-high bit rubs on the molars, this discomfort will cause the horse to toss its head and otherwise express its displeasure at the situation, leading to a poor performance.

If the horse tosses its head or attempts to evade contact with a bit, improper fit is usually the cause, but other factors should be considered. A rider needs to verify with a veterinarian that the horse does not have a dental problem. Then bit fit and the type of bit needs to be considered. But finally, the skills of the rider may be a factor. Even the gentlest bit properly adjusted may still cause discomfort to a horse in the hands of a poor rider.

Width

The snaffle should generally be no more than 1⁄2 inch wider than the horse's mouth. A horse's mouth can be measured by placing a wooden dowel or a piece of string into the mouth where the bit will go and marking it at the edges of the horse's lips. A bit that is too narrow can cause pinching (which may be very severe in a loose ring), and the pinching may lead to behavior problems when the horse experiences the discomfort. A pinching bit will also cause callousing on the lips. The lesser sin is a bit that is too wide, which does not pinch the lips, but does not allow for effective communication between horse and rider. The nutcracker effect of a jointed snaffle presents a fit issue as well; the joint of a too-wide mouthpiece will hit the roof of the horse's mouth when the reins are tightened.

Mouthpiece diameter

Competition rules require bits to have a minimum diameter, but have no upper limits on thickness. Many horsepeople believe that a fatter mouthpiece is always a milder mouthpiece, because thin mouthpieces localize the pressure on the bars of the mouth. However, the horse's mouth is filled almost completely by his tongue. Therefore, many horses (especially those with large, fleshy tongues) prefer an average diameter mouthpiece, which provides slightly more space in an already cramped mouth. Additionally, thicker mouthpieces do not give a great deal of extra bearing surface, and so generally do not help as much as many riders believe. To make a bit milder, it can be wrapped with rubber or made of a softer plastic material instead of metal.

However, mouthpieces that are extremely thin, such as wire mouthpieces or those that are only 1⁄8–1⁄4" in thickness, are never mild. These can be damaging to a horse's mouth.

See also

Citations

- Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Biting pp. 52–54

- Kapitzke Bit and Reins p. 79

- Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Biting p. 55

- Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Biting p. 68

- Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Biting p. 57

- Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Biting p. 58

- Kapitzke Bit and Reins p. 95

Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Bitting pp. 52–54 Kapitzke Bit and Reins p. 79 Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Bitting p. 55 Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Bitting p. 68 Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Bitting p. 57 Edwards Complete Book of Bits and Bitting p. 58 Kapitzke Bit and Reins p. 95

References

- Edwards, Elwyn Hartley (2004). The Complete Book of Bits & Bitting. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7153-1163-9.

- Kapitzke, Gerhard (2004). The Bit and the Reins: Developing Good Contact and Sensitive Hands. North Pomfret, VT: Trafalgar Square Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57076-275-8.

- Dr. Hilary Clayton Offers Many Prescriptions For Bits

- A fluoroscopic study of the position and action of the jointed snaffle bit in the horse's mouth