Bovista pila

Bovista pila, commonly known as the tumbling puffball, is a species of puffball fungus in the family Agaricaceae. A temperate species, it is widely distributed in North America, where it grows on the ground on road sides, in pastures, grassy areas, and open woods. There are few well-documented occurrences of B. pila outside North America. B. pila closely resembles the European B. nigrescens, from which it can be reliably distinguished only by microscopic characteristics.

| Bovista pila | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. pila Berk. & M.A.Curtis (1873) |

| Binomial name | |

| Bovista pila | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

The egg-shaped to spherical puffball of B. pila measures up to 8 cm (3 in) in diameter. Its white outer skin flakes off in age to reveal a shiny, bronze-colored inner skin that encloses a spore sac. The spores are more or less spherical, with short tube-like extensions. The puffballs are initially attached to the ground by a small cord that readily breaks off, leaving the mature puffball to be blown about. Young puffballs are edible while their internal tissue is still white and firm. B. pila puffballs have been used by the Chippewa people of North America as a charm, and as an ethnoveterinary medicine for livestock farming in western Canada.

Taxonomy

The species was described as new to science in 1873 by Miles Joseph Berkeley and Moses Ashley Curtis, from specimens collected in Wisconsin. In their short description, they emphasize the short pedicels (tube-like extensions) on the spores, and indicate that these pedicels—initially about as long as the spore is wide—soon break off.[5] According to the nomenclatural authority MycoBank,[1] taxonomic synonyms (i.e., having different type specimens) include Pier Andrea Saccardo's 1882 Bovista tabacina, Job Bicknell Ellis and Benjamin Matlack Everhart's 1885 Mycenastrum oregonense, and Andrew Price Morgan's 1892 Bovista montana. William Chambers Coker and John Nathaniel Couch called B. pila "the American representative of B. nigrescens in Europe", referring to their close resemblance.[6]

Bovista pila is commonly known as the tumbling puffball, referring to the propensity of detached puffballs to be blown about by the wind.[7] The specific epithet pila is Latin for "ball".[8]

Description

B. pila has an egg-shaped to roughly spherical fruit body measuring up to 8 cm (3.1 in) in diameter.[9] The thin (0.25 millimeter[6]) outer tissue layer (exoperidium) is white to slightly pink. Its surface texture, initially appearing as if covered with minute flakes of bran (furfuraceous), becomes marked with irregular, crooked lines (rivulose).[6] The exoperidium flakes off in maturity to reveal a thin, inner peridium (endoperidium). The color of this shiny inner skin, splotched with darker areas, resembles the metallic colors of bronze and copper. Bovista pila puffballs are attached to the ground by a small cord (a rhizomorph) that typically breaks off when the puffball is mature.[9] The interior flesh, or gleba, comprises spores and surrounding capillitial tissue.[9] Initially white and firm with tiny, irregularly shaped chambers (visible with a magnifying glass),[6] the gleba later becomes greenish and then brown and powdery as the spores mature.[9] In age, the upper surface of the puffball cracks and tears open.[10] The resilient texture of the inner peridium enables the puffball to maintain its ball-like shape after it has detached from the ground. As the old puffballs get blown around, spores get shaken out of the tears.[6]

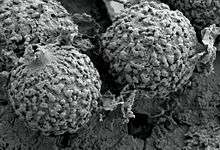

The spores of Bovista pila are spherical, smooth (when viewed with a light microscope), and measure 3.5–4.5 μm. They have thick walls and very short pedicels.[9] Basidia (spore-bearing cells) are club-shaped, measuring 8–10.5 by 14–18 μm. They are usually four-spored (rarely, some are three-spored), with unequal length sterigmata between 4 and 7.4 μm.[11] The capillitia (sterile fibers interspersed among the spores) tend to form loose balls about 2 mm in diameter.[12] The main, trunk-like branches of the capillitia are up to 15 μm in diameter, with walls that are typically 2–3 μm thick.[13]

Similar species

Characteristics typically used to identify Bovista pila in the field include its relatively small size, the metallic lustre of the endoperidium, and the presence of rhizomorphs.[14] B. plumbea is similar in appearance, but can be distinguished by its typically smaller fruit body and the blue-gray color of its inner coat. Unlike B. pila, B. plumbea is attached to the ground by a mass of mycelial fibers known as a sterile base. Microscopically, B. plumbea has larger spores (5–7 by 4.5–6.0 μm); with long pedicels (9–14 μm).[9] Another lookalike is the European B. nigrescens, which can most reliably be distinguished from B. pila by its microscopic characteristics. The spores of B. nigrescens are oval rather than spherical, rougher than those of B. pila, and have a hyaline (translucent) pedicel about equal in length to the spore diameter (5 μm).[12] The puffball Disciseda pila was named for its external resemblance to B. pila. Found in Texas and Argentina, it has much larger, warted spores that measure 7.9–9.4 μm.[15]

Habitat and distribution

Bovista pila is found in corrals, stables,[7] roadsides,[16] pastures and open woods. The puffballs fruit singly, scattered, or in groups on the ground.[9] It is also known to grow in lawns and parks.[14] The puffball spore cases are persistent and may overwinter.[7] Fruiting occurs throughout the mushroom season.[10]

Bovista pila is widely distributed in North America (including Hawaii).[17] There are few well-documented occurrences of B. pila outside North America.[18] Hanns Kreisel recorded it from Russia, in what is now known as the Sakha Republic.[19] The puffball has been tentatively identified from the Galápagos Islands,[20] and has been collected from Pernambuco and São Paulo, Brazil.[21][22] The South American material, however, has grayish-yellow coloration in the gleba, which may be indicative of not yet fully matured specimens. This renders identification of this material tentative, as unripe material may have different microscopic characteristics from mature material.[18] Although the puffball has been reported from both the European part of Turkey[23] as well as Anatolia,[24] and from Morocco,[25] reports without supporting microscopic or macroscopic information are viewed with skepticism.[18]

Uses

Edible when the interior gleba is still firm and white,[7] Bovista pila puffballs have a mild taste and odor.[14]

The puffball was used by the Chippewa people of North America as a charm, and medicinally as a hemostat.[26] In British Columbia, Canada, it is used by livestock farmers who are not allowed to use conventional drugs under certified organic programs. The spore mass of the puffball is applied to bleeding hoof trimming 'nicks', and then wrapped with breathable first-aid tape. It is also similarly used on bleeding areas resulting from disbudding, and wounds resulting from sternal abscesses.[27]

References

- "Bovista pila Berk. & M.A. Curtis". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- Saccardo PA. (1882). "Fungi boreali-americani". Michelia. 2 (8): 564–582.

- Ellis JB, Everhart BM (1885). "New species of fungi". Journal of Mycology. 1 (7): 88–93. doi:10.2307/3752368. JSTOR 3752368.

- Morgan AP. (1892). "North American Fungi. Fifth Paper". Journal of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History. 14: 141–148.

- Berkeley MJ. (1873). "Notices of North American fungi (cont.)". Grevillea. 2 (16): 49.

- Johnson MM, Coker WS, Couch JN (1974) [First published 1928]. The Gasteromycetes of the Eastern United States and Canada. New York, New York: Dover Publications. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-486-23033-7.

- Ammirati JF, McKenny M, Stuntz DE (1987). The New Savory Wild Mushroom. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-295-96480-5.

- Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 909. ISBN 978-0-89815-169-5.

- Miller HR, Miller OK Jr (2006). North American Mushrooms: A Field Guide to Edible and Inedible Fungi. Guilford, Connecticut: Falcon Guides. p. 448. ISBN 978-0-7627-3109-1.

- Desjardin DE, Wood MG, Stevens FA (2014). California Mushrooms: The Comprehensive Identification Guide. Portland; London: Timber Press. pp. 445–446. ISBN 978-1-60469-353-9.

- Johnson MM, Coker WS, Couch JN (1974) [First published 1928]. The Gasteromycetes of the Eastern United States and Canada. New York, New York: Dover Publications. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-486-23033-7.

- Ellis JB. (1889). "The genus Scleroderma in Saccardo's Sylloge". Journal of Mycology. 5 (1): 23–24. doi:10.2307/3752854. JSTOR 3752854.

- Bowerman CA, Groves JW (1962). "Notes on fungi from northern Canada. V. Gasteromycetes". Canadian Journal of Botany. 40 (1): 239–254. doi:10.1139/b62-022.

- Davis RM, Sommer R, Menge JA (2012). Field Guide to Mushrooms of Western North America. California Natural History Guides. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. pp. 364–365. ISBN 978-0-520-95360-4.

- Moravec Z. (1954). "One some species of the genus Disciseda and other gasteromycetes". Sydowia. 8 (1–6): 278–286.

- McKnight VB, McKnight KH (1987). A Field Guide to Mushrooms: North America. Peterson Field Guides. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-395-91090-0.

- Hemmes DE, Desjardin D (2002). Mushrooms of Hawai'i: An Identification Guide. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-58008-339-3.

- Jalink LM. (2010). "Additional notes on the Lycoperdaceae of the Beartooth Plateau". North American Fungi. 5 (5): 173–179. doi:10.2509/naf2010.005.00510.

- Kreisel H. (1967). "Taxonomisch-Pflanzengeographische monographie der Gattung Bovista". Beihefte zur Nova Hedwigia (in German). 25. Lehre, Germany: J. Cramer. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bates ST, Ryvarden L, Arturo X (2012). CDF Checklist of Galapagos Mushrooms: Gill fungi, porefungi, stinkhorns, coral fungi, puffballs, bird's nests, jellyfungi, rusts smuts (PDF) (Report). darwinfoundation.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- Baseia IG. (2005). "Bovista (Lycoperdaceae): dois novos registros para o Brasil" (PDF). Acta Botanica Brasilica (in Spanish). 19 (4): 899–903. doi:10.1590/S0102-33062005000400024.

- Trierveiler-Pereira L, Kreisel H, Baseia IG (2011). "New data on puffballs (Agaricomycetes, Basidiomycota) from the Northeast Region of Brazil". Mycotaxon. 111: 411–421. doi:10.5248/111.411.

- Stochev G, Asan A, Gucin F (1998). "Some macrofungi species of European part of Turkey" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Botany. 22: 341–346. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- Acar İ, Uzun Y, Demirel K, Keleş A (2015). "Macrofungi diversity of Hani (Diyarbakir/Turkey) district" (PDF). 8 (1): 28–34. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Haimed M, El Kholfy S, El-Assfouri A, Ouazzani-Touhami A, Benkirane R, Douira A (2015). "Inventory of Basidiomycetes and Ascomycetes harvested in the Moroccan Central Plateau" (PDF). International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience. 1 (1): 100–108.

- Burk WR. (1983). "Puffball usages among North American Indians" (PDF). Journal of Ethnobiology. 3 (1): 55–62.

- Lans C, Turner N, Khan T, Brauer G, Boepple W (2007). "Ethnoveterinary medicines used for ruminants in British Columbia, Canada". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 3: 11. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-3-11. PMC 1831764. PMID 17324258.