Bounded set

In mathematical analysis and related areas of mathematics, a set is called bounded if it is, in a certain sense, of finite size. Conversely, a set which is not bounded is called unbounded. The word 'bounded' makes no sense in a general topological space without a corresponding metric.

- "Bounded" and "boundary" are distinct concepts; for the latter see boundary (topology). A circle in isolation is a boundaryless bounded set, while the half plane is unbounded yet has a boundary.

Definition in the real numbers

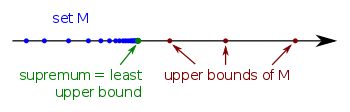

A set S of real numbers is called bounded from above if there exists some real number k (not necessarily in S) such that k ≥ s for all s in S. The number k is called an upper bound of S. The terms bounded from below and lower bound are similarly defined.

A set S is bounded if it has both upper and lower bounds. Therefore, a set of real numbers is bounded if it is contained in a finite interval.

Definition in a metric space

A subset S of a metric space (M, d) is bounded if there exists r > 0 such that for all s and t in S, we have d(s, t) < r. (M, d) is a bounded metric space (or d is a bounded metric) if M is bounded as a subset of itself.

- Total boundedness implies boundedness. For subsets of Rn the two are equivalent.

- A metric space is compact if and only if it is complete and totally bounded.

- A subset of Euclidean space Rn is compact if and only if it is closed and bounded.

Boundedness in topological vector spaces

In topological vector spaces, a different definition for bounded sets exists which is sometimes called von Neumann boundedness. If the topology of the topological vector space is induced by a metric which is homogeneous, as in the case of a metric induced by the norm of normed vector spaces, then the two definitions coincide.

Boundedness in order theory

A set of real numbers is bounded if and only if it has an upper and lower bound. This definition is extendable to subsets of any partially ordered set. Note that this more general concept of boundedness does not correspond to a notion of "size".

A subset S of a partially ordered set P is called bounded above if there is an element k in P such that k ≥ s for all s in S. The element k is called an upper bound of S. The concepts of bounded below and lower bound are defined similarly. (See also upper and lower bounds.)

A subset S of a partially ordered set P is called bounded if it has both an upper and a lower bound, or equivalently, if it is contained in an interval. Note that this is not just a property of the set S but also one of the set S as subset of P.

A bounded poset P (that is, by itself, not as subset) is one that has a least element and a greatest element. Note that this concept of boundedness has nothing to do with finite size, and that a subset S of a bounded poset P with as order the restriction of the order on P is not necessarily a bounded poset.

A subset S of Rn is bounded with respect to the Euclidean distance if and only if it bounded as subset of Rn with the product order. However, S may be bounded as subset of Rn with the lexicographical order, but not with respect to the Euclidean distance.

A class of ordinal numbers is said to be unbounded, or cofinal, when given any ordinal, there is always some element of the class greater than it. Thus in this case "unbounded" does not mean unbounded by itself but unbounded as a subclass of the class of all ordinal numbers.

See also

- Bounded function

- Local boundedness

- Order theory

- Totally bounded

References

- Bartle, Robert G.; Sherbert, Donald R. (1982). Introduction to Real Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-05944-7.

- Richtmyer, Robert D. (1978). Principles of Advanced Mathematical Physics. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-08873-3.