Bottled in bond

Bottled in bond is a label for an American-made distilled beverage that has been aged and bottled according to a set of legal regulations contained in the United States government's Standards of Identity for Distilled Spirits,[1] as originally laid out in the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897. As a reaction to widespread adulteration in American whiskey, the act made the federal government the guarantor of a spirit's authenticity, gave producers a tax incentive for participating, and helped ensure proper accounting and the eventual collection of the tax that was due. Although the regulations apply to all spirits, most bonded spirits are whiskeys in practice.

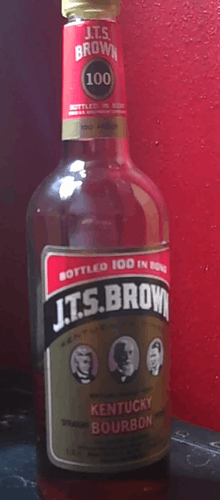

To be labeled as bottled-in-bond or bonded, the liquor must be the product of one distillation season (January–June or July–December) by one distiller at one distillery. It must have been aged in a federally bonded warehouse under U.S. government supervision for at least four years and bottled at 100 (U.S.) proof (50% alcohol by volume). The bottled product's label must identify the distillery where it was distilled and, if different, where it was bottled.[2][3] Only spirits produced in the United States may be designated as bonded.

Some consumers consider the term to be an endorsement of quality, while many producers consider it archaic and do not use it.[3] However, because bottled-in-bond whiskey must be the product of one distillation season, one distillery, and one distiller – whereas ordinary straight whiskey may be a product of the mingling of straight whiskeys (of the same grain type) with differing ages and producers within a single state – it may be regarded as a better indication of the distiller's skill, making it similar in concept to a single malt whisky, small batch whiskey, or single barrel whiskey.

History of the Bottled-in-Bond Act

One purpose of the Bottled-in-Bond Act was to create a standard of quality for Bourbon whiskey.[4] Prior to the Act's passage, much of the whiskey sold as straight whiskey was anything but. So much of it was adulterated out of greed – flavored and colored with iodine, tobacco, and other substances – that some perceived a need for verifiable quality assurance. The practice was also connected to tax law, which provided the primary incentive for distilleries to participate. Distilleries were allowed to delay payment of the excise tax on the stored whiskey until the aging of the whiskey was completed, and the supervision of the warehouse ensured proper accounting and the eventual collection of the tax. This combination of advantages led a group of whiskey distillers led by Colonel Edmund Haynes Taylor, Jr. (creator of Old Taylor bourbon) to join with then Secretary of the Treasury John G. Carlisle to fight for the Bottled-in-Bond Act. To ensure compliance, Treasury agents were assigned to control access to so-called bonded warehouses at the distilleries.

In addition to producing bonded bourbon,[5] some companies produce bonded rye whiskey, corn whiskey, and apple brandy.[6]

References

- "Chapter I – Alcohol, Tobacco Products and Firearms; Part 5 – Labeling And Advertising of Distilled Spirits". Title 27 – Alcohol, Tobacco Products and Firearms. Alcohol And Tobacco Tax And Trade Bureau, U.S. Department Of The Treasury. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- "Bottled in Bond Law & Legal Definition". USLegal.com Definitions. USLegal, Inc. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- Flicker, Jonah (September 24, 2015). "Everything you need to know about bottled-in-bond". Paste. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- Josh (May 27, 2009). "Bottled In Bond". the Bourbon Observer. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- "Bottled In Bond". The Whiskey Professor. Bernie Lubbers. October 24, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- "The Laird files". Drink Boston. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

Further reading

- Carson, Gerald. The Social History of Bourbon (The University Press of Kentucky, 1984)