Botryotrichum murorum

Botryotrichum murorum is a common soil and indoor fungus resembling members of the genus Chaetomium. The fungus has no known asexual state, and unlike many related fungi, is intolerant of high heat exhibiting limited growth when incubated at temperatures over 35 °C. In rare cases, the fungus is an opportunistic pathogen of marine animals and humans causing cutaneous and subcutaneous infection.

| Botryotrichum murorum | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. murorum |

| Binomial name | |

| Botryotrichum murorum (Corda) X. Wei Wang & Samson (2016)[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy and discovery

Chaetomium murorum was first discovered by August Carl Joseph Corda in 1837 when he sampled the fungus from a wall in Prague. The Latin name "murorum" means "wall".[2] In 2016 X. W. Wang et al. re-examined a set of cultures of Chaetomium-like fungi using phylogenetic analysis of the DNA directed RNA polymerase II subunit gene sequence. Chaetomium murorum, together with the genus Emilmuelleria, were then transferred to the genus Botryotrichum as the phylogenetic analysis confirmed that they clustered in the Botryotrichum clade. The current name for C. murorum is B. murorum.[3]

Ecology

B. murorum is a soil fungus[4][5] also known to occur on animal dung of a range of animals[5][6] including birds.[7] It is also commonly found in indoor environment[3][4] and on crops including sugarcane,[8] rice, banana, pea, pumpkin, and cucumber.[3][4] B. murorum is mesophilic with the optimum growing temperature of 20–30 °C (68–86 °F). It exhibits limited growth rate at 35 °C and above.[4] This species grows on a wide range of microbiological growth media under standard clinical laboratory culture conditions, including oatmeal agar (OA), potato carrot agar (PCA), dichloran 18% glycerol agar (DG18),[3] malt extract agar (MEA),[3][9] and has shown to be able to metabolize keratin.[9] Along with other close related species of Chaetomium such as C. globosum and C. funicola, B. murorum can degrade cellulose material in paper,[6][10] as it expresses cellulase,[10] xylanase, peroxidase, and laccase activities. The fungus can be utilized in waste degradation biotechnology.[10]

Morphology

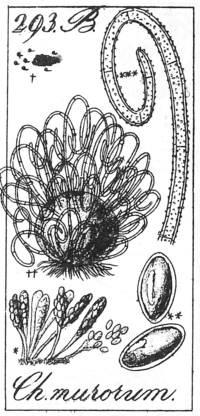

In MEA medium, the ascoma of the Chaetomiaceae-like species is categorized as perithecium with unique ornamentation attached to it.[4] It appears to be brownish or purplish, lemon shaped, with jigsaw-puzzle like (textura epidermoidea) or interwoven (textura intricata) outer walls. The ascoma is typically 160-320 μm in height and 150-279 μm in diameter. The iconic long wavy terminal hair is four times longer than the ascoma, which can grow up to 3 mm long, ending with a curly tip.[11] The ascoma also has shorter, wavy lateral hairs.[3] The asci grow in bundles, usually club-shaped, and usually form eight irregularly arranged, 12–16.5 x 7–8.5 μm ball-shaped ascospores, with apical germ pores. The ascospores turn brown when mature.[3][4][11] Although it is theoretically capable to reproduce asexually, only sexual morph is observed.[3] The appearance and growth rate of B. murorum colonies vary depending on the growth medium. For example, MEA medium colonies appear to be unpigmented (white in colour) or light brown,[12][3] and OA medium colonies appear to be purple at the center and unpigmented at the surrounding area.[3] A certain degree of morphological diversity is observed in different cultures of the same species.[3][5]

Pathogenesis

Even though the fungus is frequently found in indoor environment, and has been isolated from wide range of human food, only isolated subcutaneous infections due to superficial wound caused by contaminated material, such as contaminated agricultural tools, are reported.[4] The infection can cause subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis mostly in people with compromised immune systems.[4] Symptoms include lesion, pus, thickening of skin, and chromoblastomycosis-like, muriform bodies-less tumorous mass, which makes it easily to be misdiagnosed.[4] The fungus was reported to cause dark red, brownish plaques on chest and abdominal region in an agricultural worker.[4][13] As B. murorum prefers to grow in body parts with lower temperature, most infections are located in extremities, skin, and nails.[4] B. murorum can also cause cutaneous hyperplasia in marine animals.[9]

Mycotoxins

B. murorum produces the secondary metabolites Chaetoxanthone C and D,[14] which cause selective cytotoxicity towards some human protozoan parasitic pathogens, such as Trypanosoma cruzi and Plasmodium falciparum. These metabolites are candidates for antiprotozoal drug.[15] The chemical pigment isocochliodinol and neocochliodinol, unique to B. murorum and its close related fungus C. amygdalisporum,[16][17] has shown cytotoxic activity towards HeLa cells.[17]

References

- "Chaetomium murorum". Mycobank. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Corda, A.C.J. (1837). Icones Fungorum Hucusque Cognitorum. Prage.

- Wang, X.W.; Houbraken, J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Meijer, M.; Andersen, B.; Nielsen, K.F.; Crous, P.W.; Samson, R.A. (June 2016). "Diversity and taxonomy of Chaetomium and chaetomium-like fungi from indoor environments". Studies in Mycology. 84: 145–224. doi:10.1016/j.simyco.2016.11.005. PMC 5226397. PMID 28082757.

- Vit Hubka (2015). "Chaetomium". In Russell, R.; Paterson, M.; Lima, Nelson (eds.). Molecular Biology of Food and Water Borne Mycotoxigenic and Mycotic Fungi. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 211–228. ISBN 9781466559868.

- Carter, Adrian (1982). A Taxonomic Study of the Ascomycete Genus Chaetomium Kunze. Toronto: University of Toronto. p. 143.

- Seth, Hari K (1970). A Monograph of the genus Chaetomium. Lehre: J. Cramer. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-3768254373.

- Torbati, M (2016). "Morphological and molecular identification of ascomycetous coprophilous fungi occurring on feces of some bird species". Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology. 6 (3): 210–217. doi:10.5943/cream/6/3/9.

- Abdullah, Samir K.; Saleh, Yehya A. (December 2010). "Mycobiota Associated with Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) Cultivars in Iraq". Jordan Journal of Biological Sciences. 3 (4): 193–202.

- Reeb, Desray; Best, Peter B.; Botha, Alfred; Cloete, Karen J.; Thornton, Meredith; Mouton, Marnel (23 September 2010). "Fungi associated with the skin of a southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) from South Africa". Mycology. 1 (3): 155–162. doi:10.1080/21501203.2010.492531.

- Prokhorov, V. P.; Linnik, M. A. (15 September 2011). "Morphological, cultural, and biodestructive peculiarities of Chaetomium species". Moscow University Biological Sciences Bulletin. 66 (3): 95–101. doi:10.3103/S0096392511030072.

- Hoog, G.S. de (2000). Atlas clinical fungi (2nd ed.). Utrecht: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. p. 269. ISBN 9789070351434.

- von Arx, J.A.; Guarro, J.; M.J., Figueras (1986). The Ascomycete genus Chaetomium. Berlin: J. Cramer. p. 41. ISBN 978-3443510053.

- Lin, Yuanzhu; Li, Xiangyin (1995). "First Case of Phaeohyphomycosis Caused by Chaetomium Murorum in China". Chinese Journal of Dermatology. 28 (6): 367–369.

- Wang, Meng-Hua; Li, Li; Jiang, Tao; Wang, Xue-Wei; Sun, Bin-Da; Song, Bo; Zhang, Qiu-Bo; Jia, Hong-Mei; Ding, Gang; Zou, Zhong-Mei (December 2015). "Stereochemical determination of tetrahydropyran-substituted xanthones from fungus Chaetomium murorum". Chinese Chemical Letters. 26 (12): 1507–1510. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2015.10.025.

- Pontius, Alexander; Krick, Anja; Kehraus, Stefan; Brun, Reto; König, Gabriele M. (August 2008). "Antiprotozoal Activities of Heterocyclic-Substituted Xanthones from the Marine-Derived Fungus Chaetomium sp". Journal of Natural Products. 71 (9): 1579–1584. doi:10.1021/np800294q. PMID 18683985.

- Bycroft, B.W., ed. (1988). Dictionary of antibiotics and related substances. Cambridge: Chapman and Hall. pp. 411, 506. ISBN 978-0412254505.

- Moo-Young, Mmurray; Gregory, Kenneth F., eds. (1986). "Chemistry and Toxicology of Chaetomium Mycotoxins". Microbial biomass proteins. New York: Elsevier Applied Science. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-1851660858.