Botolph Wharf

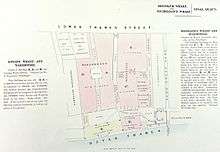

Botolph Wharf or St Botolph's Wharf was a wharf located in the City of London, on the north bank of the River Thames a short distance downstream from London Bridge.[1] It was situated between Cox and Hammond's Quay upstream and Nicholson's Wharf downstream. On the landward side, the wharf was accessed via Thames Street.[2] It had a frontage of 78 ft (24 m).[3] The wharf was used for at least a thousand years before being destroyed during the Second World War. A late 1980s office building currently occupies the site.

Origins

The wharf was one of the twenty Legal Quays of the Port of London, designated in the Act of Frauds of 1559. They were given state authorisation to serve as official landing and loading points for traders. Botolph Wharf was one of the oldest of London's riverside wharves and dated to Anglo-Saxon times. It had been part of the old Roman waterfront and the foreshore there became a key trading point for the Saxon city of Lundenburh by the 9th century. By the time King Æthelred the Unready occupied the throne, foreign ships were paying tolls to unload goods there.[4] The wharf is likely to have been constructed around 1039–40, when planks and timbers were laid out as consolidation to contain an embankment made from rubble and clay.[5] It may have been named after the nearby church of St Botolph, Billingsgate.[6] The 16th-century historian John Stow wrote that it had been part of the "Port of S. Buttolph" which was "sometime giuen or confirmed by William Conqueror to the Monkes of Westminster".[7]

One of the city gates, known as St Botolph's Gate, stood near the wharf and gave access to the north end of Old London Bridge. During the reign of Edward I it was in the possession of the Crown and was granted to Richard de Kingston.[8] Access to the wharf was recorded as having been restricted in 1344; having previously been open to all at all hours, it was closed fully at night and daytime usage was restricted to those who paid "great custom" to the keeper. The 1419 Liber Albus, the first book of English common law, mentions the wharf as the place where all boats going to Gravesend were to load, and catches of smelts and other types of coastal fish were unladen.[9]

Usage in modern times

In the 16th century the wharf was used by the Muscovy Company for their trade between England and Muscovy.[10] A century later it was owned by the Corporation of London and was leased to Sir Josiah Child in 1666.[11] By the mid-18th century the East India Company had a warehouse there.[12] As well as being a site for the shipment of cargoes, it was also a destination and departure point for passenger vessels bound for North Kent; in 1819 a packet boat travelled from there to Gravesend, from where connections could be made to Ostend in Belgium,[13] and by 1834 a hoy regularly travelled from there to Whitstable.[12] It was the central point of arrival into London for all travellers coming from Gravesend by river boat, including many who had come from continental Europe, and a "public kitchen" existed there to provide sustenance to the hungry arrivals.[14] By this time the wharf's buildings were very old and hazardous, as James Thomas Loveday noted in his 1857 London Waterside Surveys For the Use of Fire Insurance Companies; he wrote that "in the event of a fire at any part, but little hope could be entertained of saving any portion of the premises."[15]

All of the Legal Quays, including Botolph Wharf, were compulsorily purchased by HM Treasury in 1805-6. It was valued at £23,255 and the lease at £16,716.19s.[11] In 1832 the wharf was returned to private occupation when it was leased to Thomas Willkinson for a rent of £375 per quarter.[16] In the 1930s it was purchased by Nicholson's Wharves Ltd, which operated the neighbouring Nicholson's Wharf, and was incorporated into the latter wharf. Together with Nicholson's Wharf, it handled dried and green fruit, canned goods and Mediterranean produce, which was landed via a pontoon extended into the river that allowed large ships to dock there.[1] Both Botolph and Nicholson's Wharves were destroyed during the Second World War when they were struck by a V-1 flying bomb.[17] For many years afterwards, the empty site was used as a lorry depot by Billingsgate Fish Market.[1]

Current status

The site of Botolph Wharf was redeveloped in the late 1980s, after an archaeological excavation carried out between 1987–8 by the Museum of London Archaeology Service which uncovered a rich range of finds including a fourteenth-century trumpet. A glass-fronted office building designed by Covell Matthews Wheatley presently occupies the site.[1]

References

- Ellmers, Chris; Werner, Alex (2000). London's Riverscape Lost and Found. London's Found Riverscape Partnership. p. 2. ISBN 1-874044-30-9.

- Blome, Richard (1720). Billingsgate ward and Bridge ward within with its division into parishes, taken from the last survey.

- James Elmes (1831). A Topographical Dictionary of London and Its Environs: Containing Descriptive and Critical Accounts of All the Public and Private Buildings, Offices, Docks, Squares, Streets, Lanes, Wards, Liberties, Charitable, Scholastic and Other Establishments, with Lists of Their Officers, Patrons, Incumbents of Livings, &c. &c. &c. in the British Metropolis. Whittaker, Treacher and Arnot. p. 269.

- "City of London Eastcheap Conservation Area – Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD" (PDF). City of London Corporation. 22 March 2013. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- Watson, Bruce; Brigham, Trevor; Dyson, Tony (2001). London Bridge: 2000 years of a river crossing. Museum of London Archaeology Service. p. 56.

- Huelin, Gordon (1996). Vanished Churches of the City of London. Guildhall Library Pub. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-900422-42-3.

- Stow, John (1603). A Survey of London (2015 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-108-08243-3.

- Allen, Thomas (1839). The History and Antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark, and Parts Adjacent. George Virtue. p. 121.

- Atkinson, Arthur George Breeks (1898). St. Botolph Aldgate, the Story of a City Parish. Grant Richards. p. 9.

- Mayers, C P (21 July 2005). North-East to Muscovy. History Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7524-9573-6.

- Guimerá, Agustín; Ravina, Agustín Guimerá; Romero, Dolores (1996). Puertos y sistemas portuarios [Siglos 16-20]: Actas del Coloquio Internacional El sistema portuario español, Madrid, 19-21 octubre, 1995. Cedex. p. 49. ISBN 978-84-7790-251-5.

- Phillips, Hugh (1951). The Thames About 1750. Collins. p. 202.

- Boyce, Edmund (1819). The Belgian Traveller, Or A Complete Guide Through the United Netherlands. S. Leigh. p. 88.

- Brown, Robert Douglas (1978). The Port of London. T. Dalton. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-900963-87-2.

- Loveday, James Thomas (1857). Loveday's London Waterside Surveys: For the Use of Fire Insurance Companies, Showing Wharves and Granaries with the Buildings Connected on the Banks of the Thames from London Bridge to Rotherhithe [and] Tower Dock. p. 59.

- Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the English Courts of Common Law. 32. H. C. Carey & Lea. 1838. p. 229.

- London County Council (2005). The London County Council bomb damage maps, 1939–1945. London Topographical Society.