Bosnia (early medieval polity)

Bosnia (Greek: Βοσωνα/Bosona, Serbo-Croatian: Bosna), in the Early Middle Ages to early High Middle Ages was territorially and politically defined entity[1], governed at first by knyaz and then by a ruler with the ban title, from at least 838 AD.[2][3][4] Situated, broadly, around the Bosna river, between its upper and the middle course, which is a wider area of central and eastern modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. The first mention of Bosnia as an independent entity is 838 AD, with a knyaz Ratimir as its ruler.[2][3]

| Bosnia Bosna Босна | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medieval polity of Byzantine Empire | |||||||||

| 7th century AD–1154 | |||||||||

Bosnian Stećak with the Bosnian Golden lily, lilium bosniacum. | |||||||||

| Capital | Katera or Desnik | ||||||||

| Demonym | Bosnians | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 7th century AD | ||||||||

| 1154 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|

|

|

|

Ottoman era

|

|

Habsburgs

|

|

Yugoslavia

|

|

|

Geography

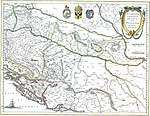

The early Bosnia, according to Vego and Mrgić, as well as Hadžijahić and Anđelić, was situated, broadly, around the Bosna river, between its upper and the middle course: in the south to north direction between the line formed by its source and the Prača river in the south, and the line formed by the Drinjača river and the Krivaja river (from Olovo, downstream to town of Maglaj), and Vlašić mountain in the north, and in the west to east direction between the Rama-Vrbas line stretching from the Neretva to Pliva in the west, and the Drina in the east, which is a wider area of central and eastern modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina.[5][6][4]

Confirmation of its emergence and territorial distribution comes from historiographical interpretation of Bar's Chronicle in modern and post-modern scholarship, which situate the state around the Upper Bosna river and the Upper Vrbas river, including Uskoplje, Pliva and Luka.[4] This also suggest that this distribution from the Bosna river valley into the Vrbas river valley is the earliest recorded. These three small parishes will later become a quintessence for emergence of Donji Kraji county, before they were reclaimed as Kotromanić's demesne, after 1416 and death of Hrvoje Vukčić.[5][6][4]

History

The western Balkans had been reconquered from "barbarians" by Byzantine Emperor Justinian (r. 527–565). Sclaveni (Slavs) raided the western Balkans, including Bosnia, in the 6th century.[7] The De Administrando Imperio (DAI; 949-960) mentions Bosnia (Βοσωνα/Bosona) as a "small/little land" (or "small country",[8] χοριον Βοσωνα/horion Bosona),[9] in the upper course of Bosna river, settled by Slavs who in time created their own unit with a ruler calling himself a Bosnian.[10][11][12][13]

As for the question of whether the inhabitants of Bosnia were really Croat or really Serb in 1180, it cannot be answered, for two reasons: first, because we lack evidence, and secondly, because the question lacks meaning. We can say that the majority of the Bosnian territory was probably occupied by Croats – or at least, by Slavs under Croat rule – in the seventh century; but that is a tribal label which has little or no meaning five centuries later. The Bosnians were generally closer to the Croats in their religious and political history; but to apply the modern notion of Croat identity (something constructed in recent centuries out of religion, history, and language) to anyone in this period would be an anachronism. All that one can sensibly say about the ethnic identity of the Bosnians is this: they were the Slavs who lived in Bosnia.[14][15]

Also, Serbs settled in south, in Zahumlje and Travunija (south-east in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina);[16] it was referred to only once, at the end of the 32nd chapter on the Serbs (a chapter overall drawn from older writings).[8] This is the first mention of a Bosnian entity; at the time it was a geographic, not a national, entity.[8] In the Early Middle Ages, Fine, Jr. believes that what is today western Bosnia and Herzegovina was part of Croatia, while the east was Serbian,[17] although, the harsh and usually inaccessible elevated terrains of Upper Bosnia was most likely never under direct control of either of the two Slavic states, but more under its own political rule. This claim is reinforced by the Byzantine writer Cinnamus, who wrote:

..the river Drina which has its source somewhere in the upper lands, separates Bosnia from Serbia, Bosnia, isn't subordinated to the Serb ruler, instead the people in it have a special way of life and governance.[18]

Historical and archaeological information on early medieval Bosnia is inadequate.[19] Bosnia included two inhabited towns[20] according to DAI, Katera and Desnik.[21] Katera has been identified as Kotorac near Sarajevo, however, according to Bulić 2013 archaeology refutes this; it may have been Kotor Varoš (the site of Bobac or Bobos), although it only includes late medieval findings to date.[20] Desnik remains unidentified, but was thought to be near Dešanj.[20] If DAI's kastra oikoumena does not designate inhabited towns, but ecclesiastical centres (as theorized by Tibor Živković), the towns might be Bistua (Zenica or Vitez) and Martar (probably Konjic).[20]

Expert historians have established that the medieval Bosnian polity stretched from the Sarajevo field in the south to the Zenica field in the north, the eastern boundary being the Prača valley towards the Drina, the western along the Lepenica and Lašva valleys.[8] Nucleus where first state had developed is believed to be in Visoko valley.[22][23] .

After the death of Serbian ruler that conquered territories Časlav (r. ca. 927–960), land of Bosnia detached from the Serbian state, together with Raška, Travunija, Zahumlje and Paganija, became politically separated.[4][24] Bulgaria briefly subjugated Bosnia at the turn of the 10th century, after which followed period of Byzantine rule.[24] In the 11th century, Bosnia was briefly part of the state of Duklja (predecessor of Montenegro).[24]

At the end of 12th century, the Banate of Bosnia emerged under its first ruler Ban Borić. After Ban Kulin Bosnia was by practical means an independent state, but that was constantly challenged by Hungarian kings who tried to reestablish its authority.[25]

See also

- Banate of Bosnia

- Kingdom of Bosnia

- Usora (region)

- Soli (region)

- Visoko during the Middle Ages

References

- Vego 1982, p. 104"All the aforementioned historical sources on the use of the title "King of Rama" in the offices of Hungarian kings and feudal lords and some foreign diplomats in Europe must be proof of independent Bosnia the period of Early Middle Ages, especially in the early 12th century, regardless of temporary conquests of Bosnia by neighboring and foreign rulers"

Original source: Svi pomenuti historijski izvori o upotrebi naslova "kralj Rame" u kancelarijama ugarskih kraljeva i feudalaca i nekih stranih diplomata u Evropi, moraju se smatrati da označavaju samostalnu Bosnu već u ranom periodu srednjeg vijeka, naročito u početku 12. vijeka, bez obzira na privremeno osvajanje Bosne od strane susjednih i stranih vladara - Vego, Marko (1982). "Postanak imena Bosna". Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države (in Serbo-Croatian). Sarajevo: Svjetlost. pp. 18, 25. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

Knez Ratimir bi bio prvi poznati knez na području Bosne kao samostalne oblasti.

- Hadžijahić, Muhamed (2004). Povijest Bosne u IX i X stoljeću (in Serbo-Croatian) (from the original University of Michigan ed.). Sarajevo: Preporod. pp. 14, 15, 32, 33, . Retrieved 28 December 2019.

Vladavina Bladinova nasljednika Ratimira može se datirati u 838. godinu.

CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Mrgić-Radojčić, Jelena (2002). Donji Kraji: Krajina srednjovekovne Bosne (in Serbo-Croatian). Filozofski fakultet. p. 32. ISBN 978-86-80269-59-7. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Hadžijahić, Muhamed (2004). "1. NAJSTARIJA POVIJEST BOSNE U DOSADAŠNJOJ HISTORIOGRAFIJI". Povijest Bosne u IX i X stoljeću (in Serbo-Croatian). Sarajevo: Preporod. pp. 9–20. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Vego, Marko (1982). "Granice najstarije oblasti Bosne". Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države (in Serbo-Croatian). Sarajevo: Svjetlost. pp. 26–33. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Fine 1991, p. 32.

- Kaimakamova & Salamon 2007, p. 244.

- Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka (in Bosnian). Preporod. p. 25. ISBN 978-9958-815-00-3.

- Fine 1991, p. 53

- "The Charter of Kulin is the best legally Bosnia and Herzegovina state document". Institute For Research of Genocide Canada (IGC) (in English and Serbo-Croatian). 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- "Šta je Povelja Kulina bana bez domovine". Al Jazeera Balkans (in Bosnian). 2 January 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Pejo Ćošković (July 2000). "Pogledi o povijesti Bosne i crkvi bosanskoj". Journal - Institute of Croatian History (in Croatian). Faculty of Philosophy, Zagreb, FF press. 32-33 (1). ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

Razlikovanje Bosne od ostalih kasnije stečenih dijelova ostalo je prisutno u titulaturi bosanskih vladara tijekom čitavog srednjeg vijeka. Uvažavanje te složenosti bosanskog državnog prostora može pružiti podlogu i pomoći pri razmišljanju o etničkoj i narodnosnoj pripadnosti srednjovjekovnog bosanskog stanovništva. U tijesnoj vezi s tim je postanak i funkcioniranje naziva Bošnjani kojim su u domaćoj izvornoj građi nazivani politički podanici bosanskih vladara od vremena Stjepana II. Kotromanića. Rjeđe su taj naziv Dubrovčani talijanizirali i pisali kao Bosignani.

- Malcolm, N. (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814755617. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

- Kaimakamova & Salamon 2007, p. 244

- Fine & 1991., p. 53.

- Fine & 1991.., p. 53.

- Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka (in Bosnian). Preporod. p. 31. ISBN 9958-815-00-1.

- Bulić 2013, p. 155.

- Bulić 2013, p. 156.

- Moravcsik 1967.

- Filipović 2002, p. 203.

- Vego 1982, p. 77.

- Bulić 2013, p. 157.

- Fine, John V. A.; Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

Sources

- Malcolm, N. (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814755617. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

- Bataković, Dušan T. (1996). The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina: History and Politics. Paris: Dialogue.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka (in Bosnian). Preporod. ISBN 978-9958-815-00-3.

- Bulić, Dejan (2013). "The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine Period on the Later Territory of the South-Slavic Principalities, and their re-occupation". The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD). Belgrade: The Institute for History. pp. 137–234.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaimakamova, Miliana; Salamon, Maciej (2007). Byzantium, new peoples, new powers: the Byzantino-Slav contact zone, from the ninth to the fifteenth century. Towarzystwo Wydawnicze "Historia Iagellonica". ISBN 978-83-88737-83-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mrgić-Radojčić, Jelena (2004). "Rethinking the Territorial Development of the Medieval Bosnian State". Историјски часопис. 51: 43–64.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Živković, Tibor (2008). Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West 550-1150. Belgrade: The Institute of History.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Živković, Tibor (2010). "On the Beginnings of Bosnia in the Middle Ages". Spomenica akademika Marka Šunjića (1927-1998). Sarajevo: Filozofski fakultet. pp. 161–180.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vego, Marko (1982), Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države (jezik: srpskohrvatski), Svjetlost

- Filipović, Milenko S. (2002), Visočka nahija (jezik: srpski), Mak

- Vego, Marko (1982). Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države. Sarajevo: Svjetlost.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)