Borda–Carnot equation

In fluid dynamics the Borda–Carnot equation is an empirical description of the mechanical energy losses of the fluid due to a (sudden) flow expansion. It describes how the total head reduces due to the losses. This is in contrast with Bernoulli's principle for dissipationless flow (without irreversible losses), where the total head is a constant along a streamline. The equation is named after Jean-Charles de Borda (1733–1799) and Lazare Carnot (1753–1823).

This equation is used both for open channel flow as well as in pipe flows. In parts of the flow where the irreversible energy losses are negligible, Bernoulli's principle can be used.

Formulation

The Borda–Carnot equation is:[1][2]

where

- ΔE is the fluid's mechanical energy loss,

- ξ is an empirical loss coefficient, which is dimensionless and has a value between zero and one, 0 ≤ ξ ≤ 1,

- ρ is the fluid density,

- v1 and v2 are the mean flow velocities before and after the expansion.

In case of an abrupt and wide expansion the loss coefficient is equal to one.[1] In other instances, the loss coefficient has to be determined by other means, most often from empirical formulae (based on data obtained by experiments). The Borda–Carnot loss equation is only valid for decreasing velocity, v1 > v2, otherwise the loss ΔE is zero – without mechanical work by additional external forces there cannot be a gain in mechanical energy of the fluid.

The loss coefficient ξ can be influenced by streamlining. For example, in case of a pipe expansion, the use of a gradual expanding diffuser can reduce the mechanical energy losses.[3]

Relation to the total head and Bernoulli's principle

The Borda–Carnot equation gives the decrease in the constant of the Bernoulli equation. For an incompressible flow the result is – for two locations labelled 1 and 2, with location 2 downstream to 1 – along a streamline:[2]

with

- p1 and p2 the pressure at location 1 and 2,

- z1 and z2 the vertical elevation – above some reference level – of the fluid particle, and

- g the gravitational acceleration.

The first three terms, on either side of the equal sign are respectively the pressure, the kinetic energy density of the fluid and the potential energy density due to gravity. As can be seen, pressure acts effectively as a form of potential energy.

In case of high-pressure pipe flows, when gravitational effects can be neglected, ΔE is equal to the loss Δ(p+½ρv2):

For open channel flows, ΔE is related to the total head loss ΔH as:[1]

- with H the total head:[4]

where h is the hydraulic head – the free surface elevation above a reference datum: h = z + p/(ρg).

Examples

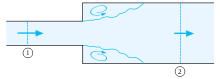

Sudden expansion of a pipe

The Borda–Carnot equation is applied to the flow through a sudden expansion of a horizontal pipe. At cross section 1, the mean flow velocity is equal to v1, the pressure is p1 and the cross-sectional area is A1. The corresponding flow quantities at cross section 2 – well behind the expansion (and regions of separated flow) – are v2, p2 and A2, respectively. At the expansion, the flow separates and there are turbulent recirculating flow zones with mechanical energy losses. The loss coefficient ξ for this sudden expansion is approximately equal to one: ξ ≈ 1.0. Due to mass conservation, assuming a constant fluid density ρ, the volumetric flow rate through both cross sections 1 and 2 has to be equal:

- so

Consequently – according to the Borda–Carnot equation – the mechanical energy loss in this sudden expansion is:

The corresponding loss of total head ΔH is:

For this case with ξ = 1, the total change in kinetic energy between the two cross sections is dissipated. As a result, the pressure change between both cross sections is (for this horizontal pipe without gravity effects):

and the change in hydraulic head h = z + p/(ρg):

The minus signs, in front of the right-hand sides, mean that the pressure (and hydraulic head) are larger after the pipe expansion. That this change in the pressures (and hydraulic heads), just before and after the pipe expansion, corresponds with an energy loss becomes clear when comparing with the results of Bernoulli's principle. According to this dissipationless principle, a reduction in flow speed is associated with a much larger increase in pressure than found in the present case with mechanical energy losses.

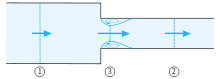

Sudden contraction of a pipe

In case of a sudden reduction of pipe diameter, without streamlining, the flow is not able to follow the sharp bend into the narrower pipe. As a result, there is flow separation, creating recirculating separation zones at the entrance of the narrower pipe. The main flow is contracted between the separated flow areas, and later on expands again to cover the full pipe area.

There is not much head loss between cross section 1, before the contraction, and cross section 3, the vena contracta at which the main flow is contracted most. But there are substantial losses in the flow expansion from cross section 3 to 2. These head losses can be expressed by using the Borda–Carnot equation, through the use of the coefficient of contraction μ:[5]

with A3 the cross-sectional area at the location of strongest main flow contraction 3, and A2 the cross-sectional area of the narrower part of the pipe. Since A3 ≤ A2, the coefficient of contraction is less than one: μ ≤ 1. Again there is conservation of mass, so the volume fluxes in the three cross sections are a constant (for constant fluid density ρ):

with v1, v2 and v3 the mean flow velocity in the associated cross sections. Then, according to the Borda–Carnot equation (with loss coefficient ξ=1), the energy loss ΔE per unit of fluid volume and due to the pipe contraction is:

The corresponding loss of total head ΔH can be computed as ΔH = ΔE/(ρg).

According to measurements by Weisbach, the contraction coefficient for a sharp-edged contraction is approximately:[6]

Derivation from the momentum balance for a sudden expansion

For a sudden expansion in a pipe, see the figure above, the Borda–Carnot equation can be derived from mass- and momentum conservation of the flow.[7] The momentum flux S (i.e. for the fluid momentum component parallel to the pipe axis) through a cross section of area A is – according to the Euler equations:

Consider the conservation of mass and momentum for a control volume bounded by cross section 1 just upstream of the expansion, cross section 2 downstream of where the flow re-attaches again to the pipe wall (after the flow separation at the expansion), and the pipe wall. There is the control volume's gain of momentum S1 at the inflow and loss S2 at the outflow. Besides, there is also the contribution of the force F by the pressure on the fluid exerted by the expansion's wall (perpendicular to the pipe axis):

where it has been assumed that the pressure is equal to the close-by upstream pressure p1.

Adding contributions, the momentum balance for the control volume between cross sections 1 and 2 gives:

Consequently, since by mass conservation ρ A1 v1 = ρ A2 v2:

in agreement with the pressure drop Δp in the example above.

The mechanical energy loss ΔE is:

which is the Borda–Carnot equation (with ξ = 1).

See also

Notes

- Chanson (2004), p. 231.

- Massey & Ward-Smith (1998), pp. 274–280.

- Garde, R. J. (1997), Fluid Mechanics Through Problems, New Age Publishers, ISBN 978-81-224-1131-7. See pp. 347–349.

- Chanson (2004), p. 22.

- Garde (1997), ibid, pp. 349–350.

- Oertel, Herbert; Prandtl, Ludwig; Böhle, M.; Mayes, Katherine (2004), Prandtl's Essentials of Fluid Mechanics, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-40437-0. See pp. 163–165.

- Batchelor (1967), §5.15.

References

- Batchelor, George K. (1967), An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66396-0, 634 pp.

- Chanson, Hubert (2004), Hydraulics of Open Channel Flow: An Introduction (2nd ed.), Butterworth–Heinemann, ISBN 978-0-7506-5978-9, 634 pp.

- Massey, Bernard Stanford; Ward-Smith, John (1998), Mechanics of Fluids (7th ed.), Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-7487-4043-7, 706 pp.