Bolsón de Mapimí

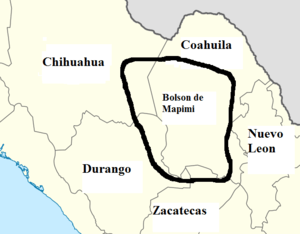

The Bolsón de Mapimí is an endorheic or internal drainage basin in which no rivers or streams drain to the sea, but rather toward the center of the basin, often terminating in swamps and ephemeral lakes. It is located in the center-north of the Mexican Plateau. The Basin is shared by the states of Durango, Coahuila, Chihuahua, and Zacatecas. It takes its name from Mapimí, a town in Durango.

The largest city in the basin is Torreón. Parts of the basin host much industrial and agricultural activity. However, most of the region is sparsely populated.

Geography

The Bolsón de Mapimí is a large area, measuring more than 200 miles (320 km) north to south and the same distance east to west, lying between 25 and 29 degrees north latitude. The total area is about 50,000 square miles (129,000 km2) and the average elevation is 3,000 feet (900 meters).[1] The Greater Bolsón de Mapimí covers adjacent areas extending north to the Rio Grande, which are similar in terrain and climate but have streams which have outlets to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Bolsón is bounded on the west by the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Conchos River basin, by the basin of the Rio Grande to the north, and by the mountain ranges of the Sierra del Carmen and Sierra Madre Oriental to the east. At its southern edge, near the state line of Zacatecas, the Bolson shades into another endorheic basin called Llanos El Salado. Major rivers flowing northward into the basin are the Nazas River and its tributaries, which originate in the Sierra Madre Occidental in Durango, and the Aguanaval River, which flows north from central Zacatecas. The two rivers terminate in the southern part of the Bolsón in an area called the Comarca Lagunera, centered on the city of Torreón, Coahuila, which formerly contained large, shallow lakes, now usually dry.

The Bolsón de Mapimí consists of desert plains separated by low mountain ranges. Cerro Centinela, which rises to 10,269 feet (3,130 m), south of Torreón is at the southern edge. Within the Bolsón most of the mountain ranges are 4,000 to 5,000 feet (1,200-1,500 m) in elevation. Los Alamitos range near the center of the Bolsón reaches 6,516 feet (1,984 m)[2]

The Bolsón is the southernmost extension of the Chihuahua Desert. The area receives between 8 and 16 inches (200 to 400 mm.) of precipitation annually, mostly falling in summer. The city of Torreón receives 9.0 inches (228 mm). Summer temperatures are hot. June is the hottest month in Torreón with an average temperature of 82.6 F (28.1 C). Winters are mild with an average temperature of 58 F (14.5 C) in December in Torreón. Freezes are common in winter.[3]

The conurbation of Torreón, with more than a million inhabitants, is the largest city. Most of the Bolsón is sparsely populated, with settlements centered on mines and areas where irrigated agriculture is possible.

History

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish the Bolsón de Mapimí was inhabited by nomadic hunter-gatherers. Bands of the Toboso Indians, of whom little is known, inhabited most of the Bolsón. In the north lived the Chisos who had a similar culture. Spanish penetration into the Bolson began in the 1590s with Jesuit missionaries, slave traders, and Tlaxcalan Indians whom the Spanish persuaded by grants of land and freedom from taxes to move north to aid in assimilating the Indians and resolving the long-running Chichimeca War.[4] The Toboso and Chisos began raiding Spanish settlements at an early date and participated in wars against Spanish settlements in 1644, 1667, and 1684. Most of the Toboso and Chisos were absorbed into the Spanish population in the early 18th century.[5]

In the 19th century the Bolsón was still largely unpopulated. In the 1840s and 1850s the Bolsón became a base for Comanche Indians from Texas who met at well-watered locations, consolidated their forces, often numbering hundreds of warriors, and struck off in every direction on destructive raids of mines and ranches.[6] (See Comanche-Mexico War)

See also

References

- "Mapimí Basin", http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/363554/Mapimi-Basin, accessed 21 Feb 2013

- Google Earth

- "Normales Climatologicas 1951-2010" Servicio Meteorológico Nacional, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-22. Retrieved 2013-02-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed February 19, 2013

- Powell, Phillip Wayne Soldiers, Indians & Silver Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952, pp. 191-199

- Griffen, William B. Indian Assimilation in the Franciscan Area of Nueva Vizcaya Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1979, pp. 4-24

- Smith, Ralph A. "The Comanche Bridge between Oklahoma and Mexico, 1843-1844" The Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 39, No. 1, 1961, p. 56

External links

- Atlas del Agua en México 2016 (Regiones hidrológicas) [Mexican Atlas of Water (Hydrological Regions) 2016] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Comisión Nacional del Agua, Subdirección General de Planeación. 2016. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- "Atlas Nacional Interactivo de México" [National Atlas of Mexico]. www.atlasdemexico.gob.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-09-17.