Germain Boffrand

Germain Boffrand (French pronunciation: [ʒɛʁmɛ̃ bɔfʁɑ̃]) (16 May 1667 – 19 March 1754) was a French architect. A pupil of Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Germain Boffrand was one of the main creators of the precursor to Rococo called the style Régence, and in his interiors, of the Rococo itself. In his exteriors he held to a monumental Late Baroque classicism with some innovations in spatial planning that were exceptional in France[1] His major commissions, culminating in his interiors at the Hôtel de Soubise, were memorialised in his treatise Livre d'architecture, published in 1745, which served to disseminate the French "Louis XV" style throughout Europe.

Biography

Born at Nantes, the son of a provincial architect, Boffrand went to Paris in 1681 to study sculpture in the atelier of François Girardon, before entering the large official practice of Jules Hardouin-Mansart. His uncle, Philippe Quinault, introduced him to prospective clients among the aristocracy of Paris and at Court. He was employed from 1689 (Kimball) on works in the Bâtiments du Roi under Mansart, notably at the Orangerie of Palace of Versailles and in Paris at Place Vendôme, where Boffrand was among the draughtsmen responsible for the first designs (from 1686) and for the Convent of the Capucins, Hôtel de Vendôme[2] From 1693 he was less employed and in 1699 he left the Bâtiments du Roi[3] to commence work, at first in Lorraine and in the Netherlands, then after his return to Paris in 1709, for a distinguished private clientele in Paris, well disposed towards his audacious innovations, such as the oval forecourt of the Hôtel Amelot de Gournay (1710–13), that were unthinkable in the royal works. In 1709, he was placed in charge of the interior apartments of the Hôtel de Soubise, where he soon succeeded the architect Pierre-Alexis Delamair (1676–1745). None of his early interiors survive, largely replaced by his spectacular Rococo work of the years following 1735.[4]

Boffrand was received by the Académie royale d'architecture in 1709. The following year he was among those employed in the additions to the Palais Bourbon. In 1732, he was appointed inspecteur général des ponts et chaussées and produced plans for restructuring Les Halles. He was a participant in the competition for the design of Place Louis XV. Named chief architect to the hôpital général in 1724, he constructed in the Île de la Cité a foundling hospital, the Hôpital des Enfants Trouvés (1727, demolished). Boffrand also worked for the hospitals at the Salpêtrière, at Bicêtre, and at the Hôtel-Dieu. He built a series of hôtels particuliers in Paris as speculative business enterprises. Of the inventive spatial arrangements in the hôtel that swiftly became the Hôtel Amelot de Gournay, Germain Brice remarked in his early 18th-century guidebook that "one will note some remarkable and daring lay-outs, which however appear rationally based, providing several amenities".[5] Boffrand's pavilion of 1712–15 that inaugurated the new quarter of the Faubourg Saint-Honoré was purchased and became the Hôtel de Duras.[6]

Abroad, Boffrand worked for the Duke of Lorraine (not yet a part of France), where he was appointed Premier Architecte to Duke Léopold in 1711, but little of significance remains.[7] He also constructed a fountain and a hunt pavilion, Bouchefort, in the gardens of the schloss belonging to the Elector of Bavaria, Maximilian II Emmanuel. In 1724 Boffrand worked on site at Würzburg with Balthasar Neumann, who had been consulting him in Paris, on the Prince-Bishop's Residenz (under construction 1719–1744). His designs were carried out in the main suite of rooms, where Fiske Kimball detected Boffrand's artistic control in the stuccowork by Johann Peter Castelli of Bonn.[8]

Among the architects trained in his atelier were François Dominique Barreau de Chefdeville, Charles-Louis Clérisseau and Emmanuel Héré de Corny, the architect of the Place Stanislas at Nancy. Boffrand's two sons collaborated in the office, both dying young, in 1732 and 1745.[9]

Last years and death

Boffrand's folio, Livre d'architecture, was published in 1745. There are no surviving caches of his drawings. In January 1745 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London.[10] Germain Boffrand died in Paris in 1754 at age 86.

Major commissions

The following commissions of Boffrand are largely taken from Fiske Kimball, The Creation of the Rococo, 1943.

In Paris

- Hôtel Le Brun, 49 rue du Cardinal-Lemoine, (1700), for Charles II Le Brun, the nephew and heir of the premier peintre du roi Charles Le Brun and a relative of Boffrand's. One of the first hôtels particuliers noted and commended by contemporary critics. Standing but gutted.

- Remodelling of the Hôtel de Mesme (1704). Demolished.

- Remodelling of the Hôtel de Livry. Demolished.

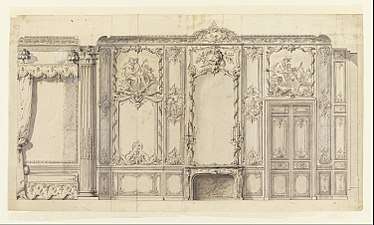

- Hôtel de Soubise, 60 rue des Francs-Bourgeois, (1704–1707) and the suite of interiors (1735–1740), Boffrand's last major work and his masterpiece (Kimball, pp 178–181), for the prince de Rohan and his wife Marie Sophie de Courcillon. Housing the Archives nationales.

- Façade of the Convent of Fathers of Mercy, 45 rue des Archives. Built for the prince de Soubise to provide a suitable street front opposite his new hôtel. Destroyed at the Revolution.

- Hôtel d'Argenson (Hôtel de la chancellerie d'Orléans), 19 rue des Bons-Enfants, (1704, demolished 1923) Built for Mme Argenson, mistress of the future Regent, and used from 1725 as the chancelry of Philippe d'Orléans during his Regency, when it was repeatedly remodelled, by Boffrand himself about 1743 (when the comte d' Argenson was given it)[11] then by Charles de Wailly in the 1780s.

- Hôtel du Premier Président (1709). Demolished.

- Hôtel de Broglie, rue Saint-Dominique (1709). Gutted.[12]

- Hôtel Petit-Luxembourg, (1709–1716). Renovation for Anne Henriette of Bavaria (1648–1723), princess Palatine, widow of the Henri Jules, Prince of Condé. Much of Boffrand's decoration survives, including the staircase with its coved cornices filled with scrolls and foliage and rounded corners.

- Transformation of the Hôtel de Mayenne, 21 rue Saint-Antoine (1709), for Charles Henri, Prince of Vaudémont. Much of the interior woodwork, some of it executed by Louis-Jacques Herpin, was removed to the Château de Champs.

- Hôtel Amelot de Gournay, 1 rue Saint-Dominique (1712). One of Boffrand's speculative hôtels, bought by Michel Amelot de Gournay, 1713.

- Hôtel de Beauharnais, also known as the Hôtel Colbert de Torcy (1714), 78 rue de Lille (1713). Now housing the German Embassy. Interiors were entirely remodelled during the Empire for prince Eugène de Beauharnais (Kimball, p. 99).

- Hôtel de Seignelay, 80 rue de Lille, (1713). The adjoining hôtel, bought by Colbert de Torcy's cousin, the marquis de Seigneley.

- Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal (1715–1725). New apartments in the corps de logis for Louis XIV's natural son, the duc du Maine, in his position as Grand Maître de l'Artillerie.

- Palais de Justice (1722). Restorations.

- Hôtel de Villars, 116 rue de Grenelle. Entrance doorway. Now the mairie of the 7th arrondissement.

In the Parisian region

Château de Roissy-en-France, 1704–1715 (destroyed) attributed to Boffrand after archeological research[13]

In Picardie

- Château de Bertangles (1730–1734) for Louis-Joseph de Clermont-Tonnerre.

In Lorraine

- Château de Lunéville (1708–1709) for Leopold, Duke of Lorraine. Damaged by fire in January 2003.

- Château de Commercy for the prince of Vaudémont

- Château de La Malgrange, Jarville-la-Malgrange near Nancy, (1711–1715) for Léopold (demolished by Stanislas). Boffrand gives sections of the two-storey oval salon in his Livre d'architecture, 1745 (Kimball, fig. 102).

- Palais d'Haroué (1720–1732), for Marc de Beauvau, prince de Craon

- Hôtel Ferraris, 29 rue du Haut-Bourgeois, Nancy, (1717–1720).

- Hôtel de Craon, 2 place Carrière, Nancy, also for Marc de Beauvau, prince of Craon

Religious architecture

- Chapelle de la Communion de l'Église Saint-Merri, 78 rue Saint-Martin, Paris, (1743)

- High altar of the cathedral of Nancy, which had been begun by Mansart in 1703 and was continued by Boffrand after Mansart's death.

- High altar of the cathedral of Nantes

- Notre-Dame de Paris, restoration of the rose window of the south transept and the crossing vaulting (1728–1729); restoration of the chapelle du Saint-Esprit (1746); cloister doorway (1748)

Civil engineering

- Bridge (the Pont-Vieux) of Pont-sur-Yonne

- Bridge of Joigny (Yonne), 1725–1728

- Bridge of Villeneuve-sur-Yonne (Yonne), 1735

Notes

- Kimball 1943, p.109.

- Kimball 1943 p. 38.

- He returned after the death of Mansart in 1708, paid from 21 March 1709 under the new administration of Robert de Cotte at the modest rate of 1000 livres a year, later increased to 1200. (Kimball 1943, pp 78, 125).

- Kimball 1943, p. 178.

- "on remarquera des dispositions extraordinaires & hasardées, lesquelles cependant paroissent fondées en raison pour plusieurs commoditez." (Brice, Description nouvelle de ce qu'il y a de plus remarquable dans la ville de Paris, 1713 edition, vol. III, p. 153, noted by Kimball, p. 99, note. Also found in the 1725 edition, vol. 4, p. 49).

- A small section of the interior was engraved for Blondel's Architecture françoise (Kimball 1943, p. 99 note).

- Kimball pp 100, 129.

- Kimball 1943, p. 149.

- Kimball 1943, p. 128, note.

- "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- The remodelled salon is illustrated in Boffrand's Livre d'architecture, 1745.

- Boiseries from the Hôtel de Broglie installed at the Musée Carnavalet appear to date from the 1730s (Kimball 1943, p 98 note.)

- Jean-Yves Dufour, Le château de Roissy-en-France, DRAC - SRA Île-de-France, April 2007, 16 p.

References

- This article incorporates some material re-edited from French Wikipedia

- Brice, Germain (1725). Nouvelle description de la ville de Paris, 8th edition, vol. 4. Paris: Julien-Michel Gandouin & François Fournier. View at Internet Archive.

- Fiske Kimball, The Creation of the Rococo (Philadelphia Museum of Art) 1943.

- (Ministère de culture) Jean-Pierre Babelon, "Célébrations nationales 2004: Germain Boffrand"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Germain Boffrand. |

- "Bohadin" at The General Biographical Dictionary (London 1812), p. 516

- François-Xavier Feller, Dictionnaire historique, p. 363 (in French).

- Livre d'architecture (1745) at INHA (in French)

- "La Vie de Philippe Quinault" by Germain Boffrand in Le théâtre de Mr Quinault, vol. 1 (1715), at Gallica