Bnei Brak

Bnei Brak or Bene Beraq (Hebrew: בְּנֵי בְּרַק ![]()

Bnei Brak

| |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Bnei Brak  Bnei Brak | |

| Coordinates: 32°05′N 34°50′E | |

| Country | |

| District | |

| Founded | 1924 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Mayor | Hanoch Zeibert |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,088 dunams (7.088 km2 or 2.737 sq mi) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 204,639 |

| • Density | 29,000/km2 (75,000/sq mi) |

| Website | www.bnei-brak.muni.il |

History

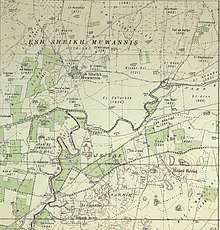

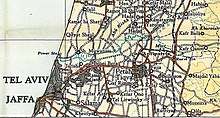

.jpg)

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 956 | — |

| 1948 | 9,300 | +14.32% |

| 1955 | 28,000 | +17.05% |

| 1961 | 47,000 | +9.02% |

| 1972 | 75,700 | +4.43% |

| 1983 | 96,100 | +2.19% |

| 1995 | 130,700 | +2.60% |

| 2008 | 151,800 | +1.16% |

| 2012 | 168,800 | +2.69% |

| 2017 | 193,800 | +2.80% |

| 2018 | 198,900 | +2.63% |

| Source: CBS | ||

Bnei Brak takes its name from the ancient Biblical city of Beneberak, mentioned in the Tanakh (Joshua 19:45) in a long list of towns of ancient Judea. Bnei Brak was founded as an agricultural village by eight Polish Hasidic families who had come to Palestine as part of the Fourth Aliyah. Yitzchok Gerstenkorn led them. It was originally a moshava, and the primary economic activity was the cultivation of citrus fruits. Due to a lack of land, many of the founders turned to other occupations, and the village began to develop an urban character. Arye Mordechai Rabinowicz, formerly rabbi of Kurów in Poland, was the first rabbi. He was succeeded by Rabbi Yosef Kalisz, a scion of the Vurker dynasty. The town was set up as a religious settlement from the outset, as is evident from this description of the pioneers: "Their souls were revived by the fact that they merited what their predecessors had not. What particularly revived their weary souls in the mornings and toward evening, when they would gather in the beis medrash situated in a special shack which was built immediately upon the arrival of the very first settlers, for tefilla betzibbur (communal prayer) three times a day, for the Daf Yomi shiur, and a Gemara shiur and an additional one in Mishnayos and the Shulchan Oruch."[3]

In 1928, the Great Synagogue was completed, and the village committee celebrated its inauguration by presenting statistics noting its development over the past four years. Bnei Brak, with a population of about 800 residents, covered about 2,000 dunams, including about 800 dunams which were citrus groves. It had 116 houses, 31 huts, six public buildings, and 48 cowsheds. In the summer of 1929, Bnei Brak was connected to the electricity grid. In the 1931 census of Palestine, the population of Benei Beraq was 956, all Jewish, in 255 houses.[4] In 1940, it had 4,500 residents and 25 factories. In 1948, the population was 9,300.

Bnei Brak achieved city status in 1950.

Bnei Brak 1925: “View of Colony with the Gate of Honor”

Bnei Brak 1925: “View of Colony with the Gate of Honor” Bnei Brak 1925

Bnei Brak 1925 Bnei Brak 1927

Bnei Brak 1927 Bnei Brak 1927

Bnei Brak 1927 Bnei Brak 1927

Bnei Brak 1927 Bnei Brak 1928, “three generations”

Bnei Brak 1928, “three generations” Bnei Brak 1928

Bnei Brak 1928 Bnei Brak, school 1931

Bnei Brak, school 1931

In April 2020, the entire city of Bnei Brak was placed under quarantine due to the coronavirus outbreak.[5]

Rabbinic presence

Rabbi Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz (the Chazon Ish) settled from Belarus to Bnei Brak in its early days, attracting a large following. Leading rabbis who have lived in Bnei Brak include Rabbi Yaakov Landau, Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler, Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky ("the Steipler"), Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman (Ponevezher Rov), Rabbi Elazar Menachem Mann Shach, Rabbi Michel Yehuda Lefkowitz, and Rabbi Aharon Yehuda Leib Shteinman. Notable rabbis who reside in Bnei Brak today are Rabbi Nissim Karelitz, Rabbi Shmuel Wosner and Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky. In the early 1950s, the Vizhnitzer Rebbe, Rabbi Chaim Meir Hager, founded a large neighborhood in Bnei Brak which continued to serve as a dynastic center under his son, Rabbi Moshe Yehoshua Hager, and under his grandsons, Rabbi Yisrael Hager and Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager.

Beginning in the 1960s, the rebbes of the Ukrainian Ruzhin dynasty (Sadigura, Husiatyn, Bohush), who had formerly lived in Tel Aviv, moved to Bnei Brak. In the 1990s, they were followed by the rebbe of Modzhitz. Unlike the former four Gerrer rebbes, who lived in Jerusalem, the current rebbe was a Bnei Brak resident until 2012. The rebbes of Alexander, Biala-Bnei-Brak, Koidenov, Machnovke, Nadvorne, Premishlan, Radzin, Shomer Emunim. Slonim-Schwarze, Strykov, Tchernobil, Trisk-Bnei-Brak and Zutshke reside in Bnei Brak. Rabbi Moshe Yehuda Leib Landau was the Rabbi of Bnei Brak until his death on March 30, 2019.[6] He was a respected authority on Jewish law and kashrut supervision. The "Rav Landau" hechsher (kosher supervision) is widely accepted. Rabbi Nissim Karelitz, chief Rabbi (av beis din) of the Lithuanian Haredi community, heads a beth din of Lithuanian and Hasidic dayanim, called She'eris Yisroel.

Demographics

According to figures by the municipality of Bnei Brak,[7] the city has a population of over 181,000 residents, the majority of whom are Haredi Jews.[8] It also has the largest population density of any city in Israel, with 25,540/km2 (66,100/sq mi). In the April 2019 Israeli legislative election, 88% of the voters chose Haredi parties. Pardes Katz, a neighborhood of about 30,000 inhabitants in northern Bnei Brak, is the sole neighborhood of the city where the majority of residents are not Haredi.

Mayors

- Yitzchok Gerstenkorn

- Moshe Begno

- Reuven Aharonovich

- Shimon Soroka

- Yitzchok Meir

- Shmuel Weinberg

- Moshe Irenstein

- Yerachmiel Boyer

- Mordechai Karelitz

- Yissochor Frankenthal

- Ya'akov Asher

- Avraham Rubinstein

- Hanoch Zeibert

Economy

One of the landmarks of Bnei Brak is the Coca-Cola bottling plant in Kahaneman St. It is owned by the Central Bottling Company (CBC), which has held the Israeli franchise for Coca-Cola products since 1968. It is among Coca-Cola's ten largest single-plant bottling facilities worldwide.[9]

Two major factories which dominated the centre of Bnei Brak for many years were the Dubek cigarette factory and the Osem food factory. As the town grew they found themselves in the middle of a residential area; both left the area. Osem's main factory is now located on Jabotinsky road in Petah Tikva, just next to Bnei Brak.

In 2011 construction started on a business district, which will include 15 office towers.[10] Several of the towers of the Bnei Brak Business Center are already built as of 2020, and other buildings won't be completed until after 2021.[11]

Culture and lifestyle

Until the 1970s, the Bnei Brak municipality was headed by religious Zionist mayors. After Mayor Gottlieb of the National Religious Party was defeated, Haredi parties grew in status and influence; since then they have governed the city. As the Haredi population grew, the demand for public religious observance increased and more residents requested the closure of their neighbourhoods to vehicular traffic on Shabbat. In a short period of time most of Bnei Brak's secular and Religious Zionist residents migrated elsewhere, and the city has become almost homogeneously Haredi. The city has one secular neighborhood, Pardes Katz.[12] Some names of streets with a Zionist connotation were renamed for prominent Haredi figures, for example, the part of Herzl St. south of Jabotinsky street was changed to HaRav Shach St. Bnei Brak is one of the two poorest cities in Israel.

Bnei Brak is home to Israel's first women-only department store,[13] only one example of gender segregation in what is viewed as an ultra-orthodox city. Bnei Brak was home to one of the original gender segregated bus lines that Israel's courts ruled were illegal. Mehadrin bus lines are a type of bus line in Israel that mostly ran in and/or between major Haredi population centers and in which gender segregation and other rigid religious rules observed by some ultra-Orthodox Jews were applied until 2011. In these sex-segregated buses, female passengers sat in the back of the bus and entered and exited the bus through the back door if possible, while the male passengers sat in the front part of the bus and entered and exited through the front door.[14] Additionally, "modest dress" was often required for women, playing a radio or secular music on the bus was avoided, advertisements were censored.[15]

The Bnei Brak municipality set up an alternative water supply, for use on Shabbat and Jewish holidays. This supply, which does not require intervention by Jews on days of rest, avoids the problems associated with Jews working on the day of rest at the national water company Mekorot. Most of the streets are closed on Shabbat and Jewish holidays.

Bnei Brak received national attention when it lost a battle to have women candidates' photos removed from advertisements for Likud's campaign. In the city's ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods, women are usually absent from advertisements and billboards because pictures of women are viewed as "sexually provocative". The city's representatives claimed they had been ordered to remove signs picturing Likud contenders such as Miri Regev and Gila Gamliel in spite of the fact that the photos showed them in modest dress. The police were summoned and they informed city officials the signs could not be removed. City officials protested that they were only trying to protect the sensitivities of religious residents. On the other hand, Orly Erez-Likhovski, head of the legal department at the Israel Religious Action Center, said this was a victory for gender equality: "“I am very happy that the officials from the Likud didn’t give up, fought the municipality and the police who first arrived on the scene. It shows that the message is starting to penetrate on every level that exclusion of women is illegal and unacceptable. It doesn't always translate to the people on the ground but we see that great progress is being made – even in Bnei Brak, even in the ultra-Orthodox sector. This is an important message.”[16]

Notable residents

- Baruch Ashlag, kabbalist

- Elazar Menachem Man Shach, leader of the ultra orthodox Lithuanian Jews.

- Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz, worldwide posek

- Chaim Kanievsky, rabbi

- Sesto Pals, writer

- Shuli Rand, actor, writer, singer

- Mary Schaps, mathematical scholar

- Dovid Shmidel, rabbi

- Aharon Yehuda Leib Shteinman, rabbi

- Motty Steinmetz, singer

- Tuvia Tenenbom, theater director and writer

- Ariel Ze'evi, judoka

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Bnei Brak is twinned with:

References

- "Population in the Localities 2019" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- No walk in the park in Bnei Brak Archived 1 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Haaretz

- "Bnei Brak at 75: City of Torah and Chassidus". Dei'ah VeDibur. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- Mills, 1932, p. 13

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/06/calls-to-seal-off-ultra-orthodox-areas-adds-tension-to-israels-virus-response

- https://hamodia.com/2019/03/31/tens-thousands-attend-levayah-bnei-braks-harav-landau-ztl/

- "Home Page". Bnei Brak Municipality. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Rosenblum, Jonathan. "L'chaim in B'nai Brak". Torah.org. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- "Dun's 100 – The Central Bottling Company Group profile". Duns100.dundb.co.il. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- Raviv, Sivan (23 March 2011). "Financial District Being Built in Bnei Brak". Ynetnews. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- https://www.khl.com/international-cranes-and-specialized-transport/tel-aviv-business-complex-build/142930.article

- "Bnei Brak". Israel Ministry of Tourism. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- Hawley, Caroline (20 April 2006). "Israeli Shop Opens Only to Women". BBC News. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- Shapira-Rosenberg, Ricky (November 2010). "Excluded, For God's Sake: Gender Segregation in Public Space in Israel". Israel Religious Action Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Kahn, Betzalel (31 October 2001). "Bus 402 from Bnei Brak to Jerusalem Launched". Dei'ah ve Dibur. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Allison Kaplan Sommer (1 January 2015). "An unlikely feminist victory in ultra-Orthodox Bnei Brak". Haaretz.

- Nahshoni, Kobi (31 May 2011). "Bnei Brak Gets Twin Sister". Ynetnews. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

Bibliography

- Brink, Edwin C.M. van den (17 April 2005), Horbat Bene Beraq, Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel

- Glick, Alexander (26 December 2010), Benē Beraq, Kinneret Street Final Archive Report, Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel

- Glick, Alexander (27 December 2012), Benē Beraq Final Archive Report, Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel

- Golan, Dor (29 November 2009), Bene Beraq, El-Waqf Final Report, Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Shadman, Amit (3 March 2010), Horbat Bene Beraq Final Report, Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel