Bleb (cell biology)

In cell biology, a bleb is a bulge of the plasma membrane of a cell, human bioparticulate or abscess with an internal environment synonymous to that of a simple cell, characterized by a spherical, bulky morphology.[2] It is characterized by the decoupling of the cytoskeleton from the plasma membrane, degrading the internal structure of the cell, allowing the flexibility required to allow the cell to separate into individual bulges or pockets of the intercellular matrix.[2] Most commonly, blebs are seen in apoptosis (programmed cell death) but are also seen in other non-apoptotic functions. Blebbing, or zeiosis, is the formation of blebs.

Formation

Bleb growth is driven by intracellular pressure generated in the cytoplasm when the actin cortex undergoes actomyosin contractions.[3] The disruption of the membrane-actin cortex interactions[2] are dependent on the activity of myosin-ATPase[4]

Bleb formation can be initiated in two ways: 1) through local rupture of the cortex or 2) through local detachment of the cortex from the plasma membrane.[5] This generates a weak spot through which the cytoplasm flows, leading to the expansion of the bulge of membrane by increasing the surface area through tearing of the membrane from the cortex, during which time, actin levels decrease.[3] The cytoplasmic flow is driven by hydrostatic pressure inside the cell.[6][7]

Physiological function

Apoptotic function

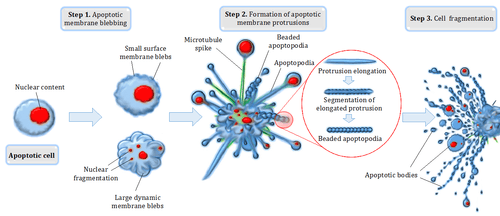

Blebbing is one of the defined features of apoptosis.[4] During apoptosis (programmed cell death), the cell's cytoskeleton breaks up and causes the membrane to bulge outward.[8] These bulges may separate from the cell, taking a portion of cytoplasm with them, to become known as apoptotic blebs.[9] Phagocytic cells eventually consume these fragments and the components are recycled.

Two types of blebs are recognized in apoptosis. Initially, small surface blebs are formed. During later stages, larger so-called dynamic blebs may appear, which may carry larger organelle fragments such as larger parts of the fragmented apoptotic cell nucleus.[10]

Nonapoptotic functions

Blebbing also has important functions in other cellular processes, including cell locomotion, cell division, and physical or chemical stresses. Blebs have been seen in cultured cells in certain stages of the cell cycle. These blebs are used for cell locomotion in embryogenesis.[11] The types of blebs vary greatly, including variations in bleb growth rates, size, contents, and actin content. It also plays an important role in all five varieties of necrosis, a generally detrimental process. However, cell organelles do not spread into necrotic blebs.

Inhibition

In 2004, a chemical known as blebbistatin was shown to inhibit the formation of blebs. This agent was discovered in a screen for small molecule inhibitors of nonmuscle myosin IIA and was shown to lower the affinity of myosin with actin,[12][13][14] thus altering the contractile forces that impinge on the cytoskeleton-membrane interface.

Notes

- Smith, Aaron; Parkes, Michael AF; Atkin-Smith, Georgia K; Tixeira, Rochelle; Poon, Ivan KH (2017). "Cell disassembly during apoptosis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 4 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2017.008.

- Fackler OT, Grosse R (Jun 2008). "Cell motility through plasma membrane blebbing". J. Cell Biol. 181 (6): 879–84. doi:10.1083/jcb.200802081. PMC 2426937. PMID 18541702.

- Charras, G. T. (January 8, 2008). "A short history of blebbing". Journal of Microscopy. 231 (3): 466–78. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02059.x. PMID 18755002.

- Wickman, G. R.; Julian, L.; Mardilovich, K.; Schumacher, S.; Munro, J.; Rath, N.; Zander, S. Al; Mleczak, A.; Sumpton, D. (2013-10-01). "Blebs produced by actin–myosin contraction during apoptosis release damage-associated molecular pattern proteins before secondary necrosis occurs". Cell Death & Differentiation. 20 (10): 1293–1305. doi:10.1038/cdd.2013.69. ISSN 1350-9047. PMC 3770329. PMID 23787996.

- Charras, G; Paluch, E (Sep 2008). "Blebs lead the way: how to migrate without lamellipodia". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 9 (9): 730–6. doi:10.1038/nrm2453. PMID 18628785.

- Charras, GT; Yarrow, JC; Horton, MA; Mahadevan, L; Mitchison, TJ (May 19, 2005). "Non-equilibration of hydrostatic pressure in blebbing cells". Nature. 435 (7040): 365–9. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..365C. doi:10.1038/nature03550. PMC 1564437. PMID 15902261.

- Tinevez, JY; Schulze, U; Salbreux, G; Roensch, J; Joanny, JF; Paluch, E (Nov 3, 2009). "Role of cortical tension in bleb growth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (44): 18581–6. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10618581T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903353106. PMC 2765453. PMID 19846787.

- Vermeulen K, Van Bockstaele DR, Berneman ZN (Oct 2005). "Apoptosis: mechanisms and relevance in cancer". Ann Hematol. 84 (10): 627–39. doi:10.1007/s00277-005-1065-x. PMID 16041532.

- van der Pol, E.; Böing, A. N.; Gool, E. L.; Nieuwland, R. (1 January 2016). "Recent developments in the nomenclature, presence, isolation, detection and clinical impact of extracellular vesicles". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 14 (1): 48–56. doi:10.1111/jth.13190. PMID 26564379.

- Tixeira R, Caruso S, Paone S, Baxter AA, Atkin-Smith GK, Hulett MD, Poon IK (2017). "Defining the morphologic features and products of cell disassembly during apoptosis". Apoptosis. 22 (3): 475–477. doi:10.1007/s10495-017-1345-7. PMID 28102458.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Barros, L. F.; Kanaseki, T.; Sabirov, R.; Morishima, S.; Castro, J.; Bittner, C. X.; Maeno, E.; Ando-Akatsuka, Y.; Okada, Y. (2003-01-01). "Apoptotic and necrotic blebs in epithelial cells display similar neck diameters but different kinase dependency". Cell Death & Differentiation. 10 (6): 687–697. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401236. ISSN 1350-9047. PMID 12761577.

- Straight AF, Cheung A, Limouze J, Chen I, Westwood NJ, Sellers JR, Mitchison TJ (March 2003). "Dissecting temporal and Spatial control of cytokinesis with a myosin II inhibitor". Science. 299 (5613): 1743–47. Bibcode:2003Sci...299.1743S. doi:10.1126/science.1081412. PMID 12637748.

- Kovács M, Tóth J, Hetényi C, Málnási-Csizmadia A, Sellers JR (Aug 2004). "Mechanism of blebbistatin inhibition of myosin II". J Biol Chem. 279 (34): 35557–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405319200. PMID 15205456.

- Limouze J, Straight AF, Mitchison T, Sellers JR (2004). "Specificity of blebbistatin, an inhibitor of myosin II". J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 25 (4–5): 337–41. doi:10.1007/s10974-004-6060-7. PMID 15548862.

References

- Charras GT, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ, Mahadevan L (Mar 2008). "Life and times of a cellular bleb". Biophys. J. 94 (5): 1836–53. Bibcode:2008BpJ....94.1836C. doi:10.1529/biophysj.107.113605. PMC 2242777. PMID 17921219.

- Charras GT, Hu CK, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ (Nov 2006). "Reassembly of contractile actin cortex in cell blebs". J. Cell Biol. 175 (3): 477–90. doi:10.1083/jcb.200602085. PMC 2064524. PMID 17088428.

- Dai J, Sheetz MP (Dec 1999). "Membrane tether formation from blebbing cells". Biophys. J. 77 (6): 3363–70. Bibcode:1999BpJ....77.3363D. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77168-7. PMC 1300608. PMID 10585959.

- Drug Stops Motor Protein, Shines Light on Cell Division - FOCUS March 21, 2003. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- Hagmann J, Burger MM, Dagan D (Jun 1999). "Regulation of plasma membrane blebbing by the cytoskeleton". J. Cell. Biochem. 73 (4): 488–99. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19990615)73:4<488::AID-JCB7>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 10733343.

External links

| Look up bleb in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |