Blasting mat

A blasting mat is a mat usually made of sliced-up rubber tires bound together with ropes, cables or chains. They are used during rock blasting to contain the blast, prevent flying rocks and suppress dust.

Use

Blasting mats are used when explosives are detonated in places such as quarries or construction sites. The mats are placed over the blasting area to contain the blast, suppress noise[1] and dust as well as prevent high velocity rock fragments called fly rock (or flyrock) from damaging structures,[2] people or the environment in proximity to the blast site.[3] The amount of fly rock can be reduced by proper drilling in the bedrock for the charges, but in practice it is hard to avoid.[4]

Mats can be used singly or in layers[5] depending on the size of the blast charge, the type of mat and the amount of protection needed.[1] They can be used horizontally on the ground or vertically hanging from cranes or attached to structures. In the vertical capacity the mats are sometimes referred to as blasting curtains.[6] When used in blasting tunnels the mats can be placed in patterns designed to let the mats stabilize each other and to direct the discharge from the explosion out of the tunnel.[7]

To prevent mats from being displaced by the explosion, they can be covered with layers of soil or anchored to the ground.[4] Anchoring the mats is also essential when the blasting is done on an incline where the mats may slide down from the rock face.[8]

Blasting mats are often used in combination with blasting blankets as an additional layer over the mats. The blankets are larger than the mats designed to retain the fragments that have managed to pass through the mat. Blasting blankets are used for both horizontal and vertical blasting.[9] Blasting blankets consist of a fine-mesh strong net or industrial felt from paper mills.[10] Both mats and blankets are designed to let air and gasses from the explosion pass through the cover and retain fragments.[9]

Knowledge of the proper use of blasting mats is required in order to obtain a blaster's certificate issued by organizations such as the WorkSafeBC.[11]

Blasting mats made from used tires can serve a double purpose as road stabilizers, or road surface, in locations where roads leading to the blasting site are unstable or nonexistent,[12] or in areas where the surface needs to be protected from heavy machinery.[13]

Materials

A number of materials are used for making blasting mats and new materials with different properties are constantly being introduced into this field.[10] The most common materials are strips of old tires held together by steel cables, mats woven from manila rope or wire cables, logs or conveyor belts.[2] Layers of wire netting can also be used.[10] Several methods of assembling a blasting mat are patented.[14][15][16]

Blasting mats made from rope woven on wires were first used during the construction of the IRT Third Avenue Line in New York City in the early 1900s. They were used to protect the surrounding buildings and were favored since they prevented fly rock but vented gasses.[17]

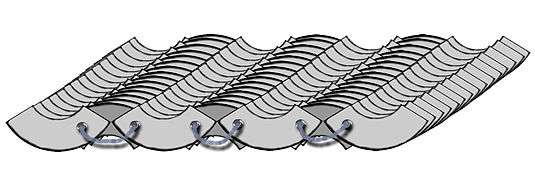

Mats made from recycled tires can be fashioned in a number of ways depending on how the tires are cut. Some examples are tread mats, sidewall mats and mats from non-flattened sections of tires.[18][14]

- Three types of tire blasting mats

Tread mat

Tread mat Sidewall mat

Sidewall mat Quarter tire mat

Quarter tire mat

Manufacturing

The manufacturing of blasting mats is integrated with the mining industry and many companies specialize in making mats,[19] especially those made from recycled tires.[20]

Military use

When charges are used to dig foxholes, an improvised blasting mat made from whole tires tied together with rope to reduce noise and fly rock, is recommended in the A Soldiers Handbook (United States). A tarp may also be used as a blasting blanket.[21]

Accidents

Over the years, a number of incidents with fatal outcomes have been caused by fly rock. In most of these, blasting mats were not used or they were placed over the blasting face in an incorrect manner.[22] Such an incident occurred in August 2015, in Cape Ray, Newfoundland and Labrador when a 7 kg (15 lb) fly rock travelled about 250 m (820 ft) from the blast site and crashed through the kitchen ceiling of a nearby house.[1]

Although designed to prevent accidents, as blasting mats weigh between 3,000 and 6,000 lb (1,400 and 2,700 kg), they have also caused injuries when falling on workers on construction sites.[23]

Blasting mats must be thoroughly inspected before each use to ensure there are no blown out segments or broken cables, by a blaster. Blasting mats will deteriorate with each use to the point where they become ineffective for their intended purpose. Only trained experienced and adequately supervised crews should be used in the placement of these devices over a loaded shot. A common complaint is accidental breakage of bus wires, leg wires or pinching off the non electric tubes that may result in the misfire of the shot.

References

- "Incidents like Cape Ray blasting mishap deemed rare". www.cbc.ca. CBC News. 27 August 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- Pal Roy, Pijush (2005). Rock Blasting: Effects and Operations (Illustrated ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-415-37230-5.

- Ghose, Ajoy K. (2000). Mining, Challenges of the 21st Century. APH Publishing. p. 383. ISBN 8176481580.

- Wyllie, Duncan C.; Mah, Chris (2004). Rock Slope Engineering (4 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 270–271. ISBN 0-415-28000-1.

- Bulletin – Association for Preservation Technology, Volym 30–31. Association for Preservation Technology. 1999. p. 70.

- Whiteside, P. G. D. (1987). The role of geology in urban development. Hong Kong: Geological Society of Hong Kong. p. 170.

- Redmond, Steve; Romero, Victor, eds. (2011). 2011 Rapid Excavation and Tunneling Conference Proceedings. Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration, Inc. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-87335-343-4.

- Gustafsson, Rune (1973). Swedish blasting technique. SPI [(box 20)].

- Hansen, T. C., ed. (2004). Recycling of Demolished Concrete and Masonry (Illustrated ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 284. ISBN 0-203-62645-1.

- Gustafsson, Rune (1981). Blasting technique. Vienna: Dynamit Nobel. pp. 122–127.

- "Blasting Examiners Protocols" (PDF). www2.worksafebc.com. WorkSafeBC. 1 May 2011. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Goldberg, Jerry (31 January 1989). "Construction mat formed from discarded tire beads and method for its use" (PDF). www.docs.google.com. United States Patent. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "What is BLAST MAT (a blasting mat)". www.blastmat.com. BlastMat.com. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Hammel, J. R. (1 March 1960). "2,926,605 Blasting mats" (PDF). www.docs.google.com. United States Patent Office. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Alexander Robertson, Thomas; King, John Alfred (16 March 1976). "Blasting Mats" (PDF). www.docs.google.com. United States Patent. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Wikner, Per Folke (5 March 1968). "Blasting Mat" (PDF). www.docs.google.com. United States Patent Office. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Wire Rope Blasting Mat". www.idealblasting.com. IDEAL SUPPLY, INC. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Products". www.blastingmats.com. Four Star Blasting Mats. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Saarinen, Oiva W. (1999). Between a Rock and a Hard Place. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 215. ISBN 0-88920-320-2.

- Resource Recycling, Volym 22. Resource Conservation Consultants. 2003. p. 48.

- Ledgard, Jared (2007). A Soldiers Handbook, Volume 1: Explosives Operations. Lulu.com. p. 557. ISBN 978-0-615-14794-9.

- Hill, William (10 December 2013). "Dangers posed to highway 7 by hidden quarry flyrock" (PDF). www.crcrockwood.org. William Hill mining consultants ltd. pp. 9–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "Cicillini v New York City Tr. Auth". www.law.justia.com. Justia. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.