Blasius boundary layer

In physics and fluid mechanics, a Blasius boundary layer (named after Paul Richard Heinrich Blasius) describes the steady two-dimensional laminar boundary layer that forms on a semi-infinite plate which is held parallel to a constant unidirectional flow. Falkner and Skan later generalized Blasius' solution to wedge flow (Falkner–Skan boundary layer), i.e. flows in which the plate is not parallel to the flow.

Prandtl's boundary layer equations

Using scaling arguments, Ludwig Prandtl[1] has argued that about half of the terms in the Navier-Stokes equations are negligible in boundary layer flows (except in a small region near the leading edge of the plate). This leads to a reduced set of equations known as the boundary layer equations. For steady incompressible flow with constant viscosity and density, these read:

Continuity:

-Momentum:

-Momentum:

Here the coordinate system is chosen with pointing parallel to the plate in the direction of the flow and the coordinate pointing towards the free stream, and are the and velocity components, is the pressure, is the density and is the kinematic viscosity.

The -momentum equation implies that the pressure in the boundary layer must be equal to that of the free stream for any given coordinate. Because the velocity profile is uniform in the free stream, there is no vorticity involved, therefore a simple Bernoulli's equation can be applied in this high Reynolds number limit constant or, after differentiation: Here is the velocity of the fluid outside the boundary layer and is solution of Euler equations (fluid dynamics).

Von Kármán Momentum integral and the energy integral for Blasius profile reduce to

where is the wall shear stress, is the wall injection/suction velocity, is the energy dissipation rate, is the momentum thickness and is the energy thickness.

A number of similarity solutions to this equation have been found for various types of flow, including flat plate boundary layers. The term similarity refers to the property that the velocity profiles at different positions in the flow are the same apart from a scaling factor. These solutions are often presented in the form of non-linear ordinary differential equations.

Blasius equation - first-order boundary layer

Blasius[2] proposed a similarity solution for the case in which the free stream velocity is constant, , which corresponds to the boundary layer over a flat plate that is oriented parallel to the free flow. Self-similar solution exists because the equations and the boundary conditions are invariant under the transformation

where is any positive constant. He introduced the self-similar variables

where is the boundary layer thickness and is the stream function, in which the newly introduced normalized stream function, , is only a function of the similarity variable. This leads directly to the velocity components

Where the prime denotes derivation with respect to . Substitution into the momentum equation gives the Blasius equation

The boundary conditions are the no-slip condition, the impermeability of the wall and the free stream velocity outside the boundary layer

This is a third order non-linear ordinary differential equation which can be solved numerically, e.g. with the shooting method.

The limiting form for small is

and the limiting form for large is

The appropriate parameters to compare with the experimental observations are displacement thickness , momentum thickness wall shear stress and drag force acting on a length of the plate, which are given for the Blasius profile

The factor in the drag force formula is to account both sides of the plate.

Uniqueness of Blasius solution

The Blasius solution is not unique from a mathematical perspective,[3]:131 as Ludwig Prandtl himself noted it in his transposition theorem and analyzed by series of researchers such as Keith Stewartson, Paul A. Libby.[4] To this solution, any one of the infinite discrete set of eigenfunctions can be added, each of which satisfies the linearly perturbed equation with homogeneous conditions and exponential decay at infinity. The first of these eigenfunctions turns out be the derivative of the first order Blasius solution, which represents the uncertainty in the effective location of the origin.

Second-order boundary layer

This boundary layer approximation predicts a non-zero vertical velocity far away from the wall, which needs to be accounted in next order outer inviscid layer and the corresponding inner boundary layer solution, which in turn will predict a new vertical velocity and so on. The vertical velocity at infinity for the first order boundary layer problem from the Blasius equation is

The solution for second order boundary layer is zero. The solution for outer inviscid and inner boundary layer are[3]:134

Again as in the first order boundary problem, any one of the infinite set of eigensolution can be added to this solution. In all the solution can be considered as a Reynolds number.

Third-order boundary layer

Since the second order inner problem is zero, the corresponding corrections to third order problem is null i.e., the third order outer problem is same as second order outer problem.[3]:139 The solution for third-order correction don't have an exact expression, but inner boundary layer expansion have the form,

where is the first eigensolution of the first order boundary layer solution (which is derivative of the first order Blasius solution) and solution for is nonunique and the problem is left with an undetermined constant.

Blasius boundary layer with suction

Suction is one of the common methods to postpone the boundary layer separation.[5] Consider a uniform suction velocity at the wall . Bryan Thwaites[6] showed that the solution for this problem is same as the Blasius solution without suction for distances very close to the leading edge. Introducing the transformation

into the boundary layer equations leads to

with boundary conditions,

Von Mises transformation

Iglisch obtained the complete numerical solution in 1944.[7] If further von Mises transformation[8] is introduced

then the equations become

with boundary conditions,

This parabolic partial differential equation can be marched starting from numerically.

Asymptotic suction profile

Since the convection due to suction and the diffusion due to the solid wall are acting in the opposite direction, the profile will reach steady solution at large distance, unlike the Blasius profile where boundary layer grows indefinitely. The solution was first obtained by Griffith and F.W. Meredith.[9] For distances from the leading edge of the plate , both the boundary layer thickness and the solution are independent of given by

Stewartson[10] studied matching of full solution to the asymptotic suction profile.

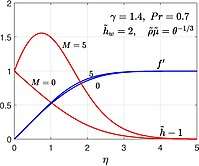

Compressible Blasius boundary layer

Here Blasius boundary layer with a specified specific enthalpy at the wall is studied. The density , viscosity and thermal conductivity are no longer constant here. The equation for conservation of mass, momentum and energy become

where is the Prandtl number with suffix representing properties evaluated at infinity. The boundary conditions become

- ,

- .

Unlike the incompressible boundary layer, similarity solution exists only if the transformation

holds and this is possible only if .

Howarth transformation

Introducing the self-similar variables using Howarth–Dorodnitsyn transformation

the equations reduce to

where is the specific heat ratio and is the Mach number, where is the speed of sound. The equation can be solved once are specified. The boundary conditions are

The commonly used expressions for air are . If is constant, then . The temperature inside the boundary layer will increase even though the plate temperature is maintained at the same temperature as ambient, due to dissipative heating and of course, these dissipation effects are only pronounced when the Mach number is large.

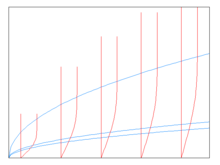

First-order Blasius boundary layer in parabolic coordinates

Since the boundary layer equations are Parabolic partial differential equation, the natural coordinates for the problem is parabolic coordinates.[3]:142 The transformation from Cartesian coordinates to parabolic coordinates is given by

- .

Footnotes

- Prandtl, L. (1904). "Über Flüssigkeitsbewegung bei sehr kleiner Reibung". Verhandlinger 3. Int. Math. Kongr. Heidelberg: 484–491.

- Blasius, H. (1908). "Grenzschichten in Flüssigkeiten mit kleiner Reibung". Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 56: 1–37.

- Van Dyke, Milton (1975). Perturbation methods in fluid mechanics. Parabolic Press. ISBN 9780915760015.

- Libby, Paul A., and Herbert Fox. "Some perturbation solutions in laminar boundary-layer theory." Journal of Fluid Mechanics 17.3 (1963): 433-449.

- Rosenhead, Louis, ed. Laminar boundary layers. Clarendon Press, 1963.

- Thwaites, Bryan. On certain types of boundary-layer flow with continuous surface suction. HM Stationery Office, 1946.

- Iglisch, Rudolf. Exakte Berechnung der laminaren Grenzschicht an der längsangeströmten ebenen Platte mit homogener Absaugung. Oldenbourg, 1944.

- Von Mises, Richard. "Bemerkungen zur hydrodynamik." Z. Angew. Math. Mech 7 (1927): 425-429.

- Griffith, A. A., and F. W. Meredith. "The possible improvement in aircraft performance due to the use of boundary layer suction." Royal Aircraft Establishment Report No. E 3501 (1936): 12.

- Stewartson, K. "On asymptotic expansions in the theory of boundary layers." Studies in Applied Mathematics 36.1-4 (1957): 173-191.

References

- Parlange, J. Y.; Braddock, R. D.; Sander, G. (1981). "Analytical approximations to the solution of the Blasius equation". Acta Mech. 38 (1–2): 119–125. Bibcode:1981AcMec..38..119P. doi:10.1007/BF01351467.

- Pozrikidis, C. (1998). Introduction to Theoretical and Computational Fluid Dynamics. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-509320-9.

- Schlichting, H. (2004). Boundary-Layer Theory. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-66270-9.

- Wilcox, David C. Basic Fluid Mechanics DCW Industries Inc. 2007

- Boyd, John P. (1999), "The Blasius function in the complex plane", Experimental Mathematics, 8 (4): 381–394, doi:10.1080/10586458.1999.10504626, ISSN 1058-6458, MR 1737233