Blackamoor (decorative arts)

Blackamoor is a European art style from the Early Modern period depicting highly stylized figures, usually African males but sometimes other non-European peoples, in subservient or exoticized form. Blackamoor is often found in sculpture, jewelry, furniture, and decorative art.

In the Iberian peninsula historically this word does not exist. The Castilian word for the moor was moro, Portuguese: mouro and for a black negro, Portuguese: negro, preto, but there has never been an Iberian word merging the two meanings. This is because the terms simply referred to Muslims regardless of ethnicity. The same can be said of the French cognate maure.

The term Blackamoor is now viewed by some as racist and culturally insensitive.[1] Blackamoor is still widely produced in Italy (mainly Venice) with the United States as the biggest importer in the world.[2][3]

Jewelry and decorative arts

As jewelry, such figures usually appear in antique Venetian (though nowadays they can be made anywhere) earrings, bracelets, cuff links, and brooches. Some contemporary craftsmen continue to make individual pieces, but it is rare because of the issues with the depiction of dark-skinned people as "exotic" and decorative. They are also traditional types of jewelry based on legend in Rijeka, such as earrings and brooches under the name Morčić.

The blackamoor is typically male, depicted with a head covering, usually a turban, and covered in rich jewels and gold leaf. They are typically enamelled, carved from ebony or painted black to contrast with the bright colors of the embellishments. Depictions may only represent the head, or head and shoulders, facing the viewer in a symmetrical pose.

In decorative sculpture the full body is depicted, either to hold trays as virtual servants or bronze sconces to hold candles or light fixtures. They may be incorporated into small stands, tables, or andirons. They are often portrayed in pairs. Andrea Brustolon (1662–1732) was the most important sculptor of blackamoors. Often these blackamoors are in acrobatic positions that would be impossible to hold for any extended length of time for a real person.

Collections

One example of a blackamoor in the arts is the Mohr mit Smaragdstufe ("Moor with Emerald Cluster"), in the collection of the Grünes Gewölbe in Dresden, Germany. It was created by Balthasar Permoser in 1724. The statue is richly decorated with jewels and is 63.8 cm (2.09 ft) high.

Aleksandr Pushkin had a blackamoor figurine on his desk to remind him of Abram Petrovich Gannibal, his great-grandfather. This figure can be seen in his former St. Petersburg apartment, now turned into a museum.

Diana Vreeland had a famous collection of blackamoor jewelry, and Anita Pointer of the Pointer Sisters has some blackamoor pieces in her extensive collection of black memorabilia.

Heraldry

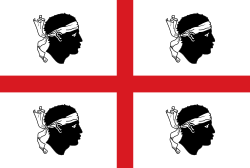

In heraldry, a blackamoor may be a charge in the blazon, or description of a coat of arms. The isolated head of a moor is blazoned "a Maure" or a "moor's head".

The reasons for the inclusion of a blackamoor head vary. The Moor's head on the crest that appears on the arms of Lord Kirkcudbright, and in consequence the modern crest badge used by Clan MacLellan is supposed to derive from the killing of a moorish bandit known as Black Morrow.[4] The blazon is a naked arm supporting on the point of a sword, a moor's head.[5] Other examples appear to depict captives; the flag of Sardinia and the neighboring Corsica depict decapitated Maures' heads with blindfolds.

Sculpture

Blackamoor figures were also used in larger sculptures, as for example on Blackamoor Bridge in Ulriksdal Palace, Sweden.

Fred Wilson,[6] an African-American sculptor, displayed an installation at the 2003 Venice Biennale that incorporated blackamoors.[7] Wilson placed wooden blackamoors carrying acetylene torches and fire extinguishers. Wilson noted that such figures are so common in Venice that few people notice them. He said, "They are in hotels everywhere in Venice ... which is great, because all of a sudden you see them everywhere. I wanted it to be visible, this whole world which sort of just blew up for me."[7]

Racism

Blackamoors have a long history in decorative art, stretching all the way back to 17th century Italy and the famous sculptor Andrea Brustolon (1662–1732). They are often mistaken for depictions of the African slaves and the ornamental pieces that they inspired; however, these decorative gems are distinctly different.[8]

In modern times, the blackamoor is considered to have racist connotations, with its association to colonialism and slavery.[1]

See also

References

- Bethan Holt (22 December 2017). "Princess Michael of Kent prompts controversy after wearing 'racist' 'blackamoor' brooch to lunch with Meghan Markle". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/culture/MAGAZINE-why-the-world-got-racist-royal-jewelry-wrong-1.5630137

- https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2015/july/awam-amkpa-on-blackamoors-at-la-pietra.html

- "MacLellan". Myclan.com. Archived from the original on 2007-03-19. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- "Mac Lellan". Celticstudio.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- "Fred Wilson biography". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- Hoban, Phoebe (2003-07-28). "The Shock of the Familiar, New York Metro, 2003". Nymag.com. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- The Antique Guild (13 August 2013). "Blackamoors". Brisbane. Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blackamoors. |