Blaberus giganteus

The Central American giant cave cockroach (Blaberus giganteus), also known as the Brazilian cockroach, is a cockroach belonging to the family Blaberidae.

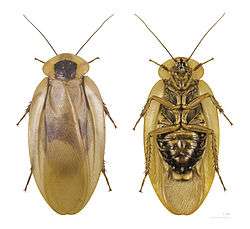

| Giant cockroach | |

|---|---|

| A live adult Blaberus giganteus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. giganteus |

| Binomial name | |

| Blaberus giganteus | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

B. giganteus is considered one of the largest cockroaches in the world, with males reaching lengths of up to 7.5 cm (3.0 in) and females 10 cm (3.9 in),[2] although others list 9 cm (3.5 in) as the maximum length.[3] These cockroaches are lightly built with flattened bodies, allowing them to hide in cracks from predators. Their bodies are brown with black markings.[4] The wingspan of these insects is usually around 15 cm (6 in).[3] Both males and females bear paired appendages (cerci) on the last abdominal segment, but only the males have a pair of tiny hair-like appendages called styli. Adults bear two pairs of wings folding back over the abdomen.[4] The heavier females are less likely to fly. These cockroaches are closely related to the first winged insects that lived in the Carboniferous coal forests about 200 million years ago.[4][5][6]

Distribution and habitat

This species is endemic to Central America and northern South America, and can be found in the rainforests,[7] in Mexico, Guatemala, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.[1] Habitat preferences include areas of high moisture and little light, such as caves, tree hollows, and cracks in rocks.[7]

Lifecycle

As typical for all roaches, individuals undergo hemimetabolous metamorphosis, which means the change from juvenile to adult is gradual.[8] The three distinct stages in their lifecycle are egg, nymph, and adult. Only adults are able to reproduce and have wings.[9] Prolonged nymphal stages, along with additional molts, can sometimes occur in B. giganteus for a number of reasons. One hypothesis is that the absence jostling and mutual stimulation which are found often in colony life could slow the developmental process.[10] In other instances, lower temperatures and reduced humidity can lead to delayed maturation and an increase in the number of molts.[10] This is a response by the insect to unfavourable habitat conditions and can also be seen as a predatory response. Their lifespans can last up to 20 months depending on habitat conditions and diet.[11]

Diet

B. giganteus is a nocturnal omnivore and a scavenger, but the majority of its diet is decaying plant material.[2] Other food choices include bat guano, fruit, seeds, and carrion.[2] It is often associated with bats roosts, both in caves and hollow dung. They also prefer sweets, meats, and starches as their daily meal.[12]

Mating

Two chemical signals play important roles in the sexual behaviour of B. giganteus.[13] The sex pheromone is released by the female and used in attracting mates that are long distances away.[13] The male produces an aphrodisiac sex hormone from his tergal glands that encourages female mounting.[13] Females choose the males with which they will mate, so this sexual selection becomes a major pressure and driving force behind natural selection.[9] Carbohydrate intake has been found to be related to male sex pheromone expression, dominance status, and attractiveness more so than protein.[9] Males have been shown to have a preference for a high-carbohydrate diet versus one focused on protein.[9] This would suggest they are actively increasing their carbohydrate consumption to maximize their reproductive fitness and attractiveness to potential female mates.[9] After mating, the female B. giganteus is pregnant for life and stores the fertilized eggs in her ootheca, where they are incubated for roughly 60 days.[13] When the eggs are about to hatch, the female expels the ootheca so the nymphs can break free and feed on their first meal, which consists of the ootheca.[13] After eating their fill, the young nymphs burrow into soil or somewhere dark and remain there until they have molted numerous times and reached maturity.[13]

Defense against fungal infection

When exposed to infection or invasion of various microorganisms, insects have two general responses of their immune systems. In B. giganteus, such an invasion elicits a humoral response, where specific proteins are produced or activated by the existence of a pathogen.[11] The fat body, which is usually associated with storing and releasing energy depending on demands, induces several novel proteins when confronted with fungal cell walls.[11] The giant cockroach exhibits adaptive humoral responses,[11] which means their immune response has a specific memory similar to what can be found in mammalian immune systems.[11] This is beneficial for long-lived individuals, as they have increased chances of encountering the same infection numerous times.[11] The biological significance of these proteins is yet to be determined, but they are known to play a role in defense against fungal infections.[11]

Endosymbiosis

The Central American giant cave cockroach has a special relationship with a genus of obligate flavobacterial endosymbiont called Blattabacterium.[2] They engage in a host microbe relationship.[2] The microbe's job is to take nitrogenous waste such as urea and ammonia and process it into amino acids that can be used by the cockroach.[2] This is very beneficial to the cockroach because overall its diet is plant-based and considered very nitrogen-poor.[2] Though carbohydrate consumption is beneficial in mating, it does not play an active role in male-to-male competition.[9]

Locomotion

Cockroaches always have three legs in synchronous contact with the ground during movement.[14] The three legs are classified as the leading leg, middle leg, and trailing leg and the leading and trailing leg from one side with the middle leg of the other side forms a tripod.[14] The leading leg pulls the body, while the trailing leg pushes the middle leg forward.[14] The middle leg is important because it acts as a pivot and creates the characteristic zigzag locomotion.[14] The process is repeated with the next tripod, and to move forward, the tripods alternate.[14] The ability of cockroaches to have ground reaction force distributed equally to these three legs is explained by joint torque minimization,[14] which has been shown to help limit mechanical, energetic, and metabolic demands, and can also decrease the axial load on a single leg.[14] Cockroaches can easily walk up a 45° slope on a smooth surface with little to no difficulty.[14] However, aged cockroaches or cockroaches with damaged tarsi can overcome such slopes only with difficulty.

Muscle metabolism and respiratory system

The rate of oxygen consumption in some animals and in insects is proportionate to body weight.[15] Oxygen consumption increases with activity and is subject to rhythmical cycles of activity exhibited in cockroaches.[15] Because cockroaches do not have lungs to breathe, they take in air through small holes on the sides of their bodies known as spiracles.[15] Attached to these spiracles are tubes called tracheae that branch throughout the body of the cockroach until they associate with each cell.[15] Oxygen diffuses across the thin cuticle and carbon dioxide diffuses out, which allows cockroaches to deliver oxygen to cells directly without relying on blood as do humans.[15] Differences in oxygen consumption occur between sexes of the same organism. Oxygen consumption in the mixed red and white muscles of mature male B. giganteus was higher when compared to mature females.[15] This is likely due to sex-related differences of sex hormones causing increased accumulation of oxidized substrates or increased concentration of enzymes in muscles in males.[15] Males have been shown to have higher levels of glycogen and mitochondria in muscle cells.[15] Because B. giganteus is so large, it is assumed to have a higher metabolic rate versus other cockroaches, such as Periplaneta americana, but in comparison, it is quite sluggish.[15] Rates of oxygen consumption are significantly higher in P. americana when compared to B. giganteus, likely due to higher daily rhythmic activity.[15]

Hemolymph

Hemolymph is the fluid used in some arthropod circulatory systems, including insects, to fill the interior hemocoel.[16] Hemolymph is composed of water, inorganic salts, and organic compounds.[16] Some of the organic compounds are free amino acids, and the contents vary by species in terms of which amino acids are present and their overall concentrations.[16] The amino acids present in B. giganteus are alanine, arginine, cysteine, glutamic acid, glycine, histidine, leucine, proline, threonine, tyrosine, and valine.[16] The amino acids present in greatest proportions were glutamic acid, alanine, glycine, and histidine.[16] The overall concentration of amino acids is roughly 265 mg/100 ml of hemolymph.[16] The presence of alanine, cysteine, glutamic acid, leucine, proline, tyrosine, and valine is shared among different species of cockroaches, such as Blattella germanica and P. americana.[16] The presence of arginine, however, is species-specific to B. giganteus.[16]

See also

References

- George Beccaloni, David C. Eades. Blattodea Species File - Blaberus giganteus

- Huang. C. Y., Sabree, Z. L. and Moran, N.A. 2012. Genome Sequence of Blattabacterium sp. Strain BGIGA, Endosymbiont of the Blaberus giganteus Cockroach. Journal of Bacteriology. 194: 4450-4451.

- Allpet Roaches

- Stephen W. Bullington Biology and Captive-Breeding of the Giant Cockroach Blaberus giganteus Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- "Blaberus Giganteus - Biggest Cockroach in the WORLD! » Gban'S & You". Gban'S & You. 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- "Blaberus - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- Smith, A. J. and Cook, T, J. 2008. Host Specificity of Five Species of Eugregarinida Among Six Species of Cockroaches (Insecta:Blattodea). Comparative Parasitology. 75: 288-291.

- Kambhampati, S. 1995. A Phylogeny of Cockroaches and Related Insects Based on DNA Sequence of Mitochondrial Ribosomal RNA genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92:2017-2020.

- South, S.H., House, C.M., Moore, A.J., Simpson, S.J., and Hunt, J. 2011. Male Cockroaches Prefer a Higher Carbohydrate Diet That Makes Them More Attractive to Females: Implications for the Study of Condition Dependence. Evolution. 65: 1594-1606.

- Banks, W.M. 1969. Observations on the Rearing and Maintenance of Blaberus giganteus(Orthoptera: Blaberidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 62: 1311-1312.

- Bidochka, M.J., St. Leger, R.J., and Roberts, D.W. 1997. Induction of Novel Proteins in Manduca sexta and Blaberus gigantus as a Response to Fungal Challenge. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 70: 184-189.

- "Blaberus Giganteus - Biggest Cockroach in the WORLD! » Gban'S & You". Gban'S & You. 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- Sreng, L. 1993. Cockroach Mating Behaviours, Sex-Pheromones, and Abdominal Glands (Dictyoptera, Blaberidae). Journal of Insect Behaviour. 6: 715-735.

- Günther, M., and Weihmann, T. 2011. The Load Distribution Among Three Legs on the Wall: Model Predictions for Cockroaches. Archive of Applied Mechanics. 81: 1269- 1287.

- Bruce, A.L. and Banks, W.M. 1973. Metabolism of Muscle of Cockroach Blaberus giganteus. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 66: 1209-1212.

- Banks, W.M., and Randolph, E.F. 1968. Free Amino Acids in the Cockroach Blaberus giganteus. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 61: 1027-1028.

- Hogue, Charles Leonard (1993). Latin American insects and entomology - University of California Press. p. 175

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blaberus giganteus. |