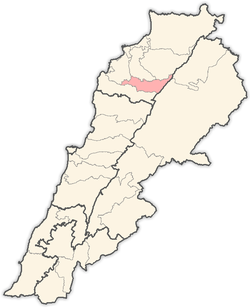

Bqarqacha

Bqarqacha also referred to as Bkerkasha بقرقاشا, is a village located in the Bsharri District in the North Governorate of Lebanon. Bkerkasha overlooks the Holy Valley of Qadisha, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, at its highest western point under mount Lebanon.

Bkerkasha is composed of three geographically separated settlements; The main village in the Becharri district, inhabited during the summer season, most of the residents during winter inhabit Barsa, Dahr Al Ein and Jadaydet Bkerkasha in Bkeftein Koura District that borders Tripoli in North Lebanon.

Etymology

According to local oral tradition, the name Bqarqacha stems from aramaic "B'qar Qosho" meaning very cold. Though the name does appear in historical records as Bir Auwshi بير اوشاي also referred to as Biir Rawshi and during the Roman Severan dynasty in the 3rd century, it was referred to as Bir’Kasha. The name have shifted from Canaanite / Phoenician to Aramaic and then Arabic which corrupted the original Canaanite / Phoenician name.[1][2] No further reference survived until the 12th century where the name reappears as Bkerkasha بقرقاشا in the Roman Catholic Maronite Church history, where an important Maronite school of Saint George flourished.[3]

Geography

The village is located at an elevation from 1450 meters above sea level to its 3050 meters highest point in the Mount Lebanon mountain range, which borders the Qarnet El Sawda and the Cedars of Lebanon. Bkerkasha overlooks the Holy Valley of Qadisha, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The valley of Qanoubin to Qadisha was the ancient route from Tripoli to Baalbeck and Hammah.

History

Bkerkasha’s Canaanite Phoenician and Judean history is evident from the extensive early and middle bronze age ruins on a mount known as Jirn Al Yehudi (Jewish burial) which was a major pagan cult center. According to Samir J. Issa the ruins remain undiscovered or academically researched due to their remote location.

Patriarch Douaihy recorded that Thacla the daughter of Father Basil of Bsharri, constructed St George Church in Bkerkasha in 1211[4] (The Annals, 104). A Bible in Smar Jbail Saint Nehra Church records the donation of two pieces of land by Slaiman Ibn Touma and his brother from Hardin in 1245 for the building of saint Nehra church. The church was built in 1525.

Bkerkasha suffered several recorded disasters in the Middle Ages

- 1526 – a wave of locusts destroyed all the crops causing famine

- 1556 November – Flood destroys most houses and watermills

- 1572 – Ottoman Empire imposes high unrealistic taxes on the residents, causing the first wave of migration

- 1635 – the end of Fakhreddines' rule caused bloody conflicts in Mount Lebanon, many resident fled to safer regions

- 1750-1759 – The Hamadeh Rulers and their mob kill and rob the village until all residents evacuate and are displaced

Economy

The economy of this town has shifted dramatically in the past 50 years, from an agricultural rural community to a more skilled and educated workforce. In 2005 agriculture represented 22% of household income[5] and represented a second stream income to most families. with an important olive oil production in the coastal area and fruits including apples and pears in the mountain area. The village is also known for its highly skilled stone masons and builders.

During the 1930s, the Bqarkasha Arida family dynasty, established the largest textile manufacturing company in the Middle East, employed hundreds of Bkarkasha residents that brought wealth and skills to the local residents and the region. The Arida Manufacturing plant represented 12 percent of the Syria – Lebanon imports during the 1930s and 1940s.[6] During World War II, the Arida company was a contributing supporter of the British Empires efforts in the war against Germany, manufacturing and supplying uniforms to the army as well as funding the development and construction of the British Air force Spitfire. George Arida for his efforts was appointed Honorary Consul British Empire.

At the end of WW II, many Bkerkasha residents migrated to Sydney Australia where skilled textile workers and textile mechanics were in demand. Sydney has the largest concentration of Bkerkasha settlement outside Lebanon.[7]

References

- Wilds, Stephan (1977). Historisch-topographische Bemerkungen zu Stefan Wilds 'Libanische Ortsnamen'," La Toponymie antique: Acts de colloque de Strasbourg. Leiden. pp. 14–16, 75–82.

- Kushke, A. Libanon : Orte mit Namen kanaanäischer Herkunft (Entwurf : A Kushke; techn. Ausfuhrung: U. Muller. pp. 81, 175.

- El Dibs, Bishop Yoseph (1886). History of Syria Al Dinyawi wa Al Diny;. Syria: Dar Nazir Aboud.

- Duwayhī, I. & Tawtal, Tawil F. (1951). Tārīkh al-azminah, 1095-1699. : (in Arabic). Bayrūt: al-Matbaaah al-Kāthūlīkīyah. OCLC 23523055.

- CDR, Lebanese Ministry of Social Affairs (2005). "CDR Lebanon Report 2005, ( World Bank project, the Ministry of Social Affairs and the United Nations Development Programme": Section 2 Point 7. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Couland, Jacques (1970). Le mouvement syndicale au Liban (1919-I946). Paris. p. 133.

- Historical Society, Australian Lebanese (1991). "Migration During the 1940s". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links

- Bqerqacha, Localiban