Bird measurement

Bird measurement or bird biometrics are approaches to quantify the size of birds in scientific studies. The measurements of the lengths of specific parts and the weights of birds varies between species, populations within species, between the sexes and depending on age and condition. In order for measurements to be useful, they need to be well defined so that measurements taken are consistent and comparable with those taken by others or at other points of time. Measurements can be useful to study growth, variation between geographically separated forms, identify differences between the sexes, age or otherwise characterize individuals birds. While certain measurements are regularly taken in the field to study living birds some others are applicable only to specimens in the museum or measurable only in a laboratory. The conventions used for measurement can vary widely between authors and works, making comparisons of sizes a matter that needs considerable care.[1]

Methods and considerations

All measurement is prone to error, both systematic and random. The measurement of certain bird characteristics can further vary greatly depending on the method used. The total length of a bird is sometimes measured by putting a dead bird on its back and gently pressing the head so that the bill point to the tail tip can be measured. This can however vary with the handling and can depend on the age and state of shrinkage in the case of measurements taken from preserved skins in bird collections. The wing length usually defined as the distance between the bend of the wing and the longest primary can also vary widely in some large birds which have a curved wing surface as well as curved primaries. The measurement can additionally vary depending on whether a flexible tape measure is used over the curve or if measured with a rigid ruler. The definition of the length of the tail can vary when some of them have elongations, forking or other modifications.[2][3][3] The weights of birds are even more prone to variability with their feeding and health condition and in the case of migratory species differ quite widely across seasons even for a single individual.

Despite the variations, measurements are routinely taken in the process of bird ringing and for other studies. Several of the measurements are considered quite constant and well defined, at least in the vast majority of birds. Although field measurements are usually univariate, laboratory techniques can often make use of multivariate measurements derived from an analysis of variation and correlations of these univariate measures. These can often indicate variations more reliably.[4][5][6]

Length

The length of a bird is usually measured from dead specimens prior to their being skinned for preservation. The measurement is made by laying the bird on its back and flattening out the head and neck gently and measuring between the tip of the bill and the tip of the tail. This measurement is however extremely prone to error and is rarely ever used for any comparative or other scientific study.[7]

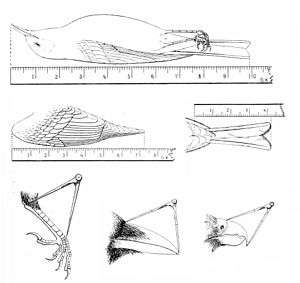

Culmen

The upper margin of the beak or bill is referred to as the culmen and the measurement is taken using calipers with one jaw at the tip of the upper mandible and the other at base of the skull or the first feathers depending on the standard chosen. In the case of birds of prey where the tip of the mandible may form a long festoon, the length of the festoon may be measured separately as well. In birds of prey the measurement is usually from the bill tip to the ceres. In some birds the distance between the back of the skull and the tip of the beak may be more suitable and less prone to variation resulting from the difficulty of interpreting the feathered base of the mandible.[8]

Head

In some cases it is more reliable to measure the distance between the back of the skull and the tip of the bill. This measure is then termed as the head. This measurement is however not suitable for use with living birds that have strong neck musculature such as the cormorants.[7]

Tarsus

The shank of the bird is usually exposed and the length from the inner bend of the tibiotarsal articulation to the base of the toes which is often marked by a difference in the scalation is used as a standard measure. In most cases the tarsus is held bent but in some cases the measurement may be made of the length of this bone as visible on the outer side of the bend to the base of the toes.

Foot

In the case of cranes and bustards, the length of the tarsus is often measured along with the length of the longest toe to the tip of the claw.[7]

Tail

The measurement of the tail is taken from the base of the tail to the tip of the longest feathers. In the case where special structures such as racquets or streamers exist, these are separately measured. In some cases the difference between the longest and shortest feathers, that is the depth of the fork or notch can also be of use.

Wing

The wing is usually measured from the bend of the wing to the tip of the longest primary feathers. Often the wings and feathers may be flattened so that the measure is maximized but in some cases the chord length with natural curvature is preferred.[4][5] In some cases the relative lengths of the longest primaries and the pattern of size variation among them can be important to measure.

Wingspan

Wingspan is the distance between wingtips when the wings are held outstretched. This is particularly prone to variation resulting from wing posture and is rarely used except as a rough indicator of size. Additionally, this cannot be easily and reliably measured in the field with living birds.

Weight

The weights of birds are notoriously variable and cannot be used as indication of size. They are however useful in quantifying growth in laboratory conditions and for use in clinical diagnostics as an indicator of physiological condition. Birds in captivity are often heavier than wild specimens. Migratory birds gain weight prior to the migratory period but lose weight during handling or temporary captivity. Dead birds tend to weigh less than in life. Even during the course of a day, the weight can vary by 5 to 10%. The male emperor penguin loses 40% of its weight during the course of incubation.[9]

References

- Baldwin, S. Prentiss; Oberholser, Harry C.; Worley, Leonard G. (1931). "Measurements of birds". Scientific Publications of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. 2: 1–165.

- Morgan J.H. (2004). "Remarks on the taking and recording of biometric measurements in bird ringing" (PDF). Ring. 26 (1): 71–78. doi:10.2478/v10050-008-0058-2.

- Goodenough AE; Stafford R; Catlin-Groves CL; Smith AL & Hart AG (2010). "Within- and among-observer variation in measurements of animal biometrics and their influence on accurate quantification of common biometric-based condition indices" (PDF). Ann. Zool. Fennici. 47: 323–334. doi:10.5735/086.047.0503.

- Bergtold, WH (1925). "The Relative Value of Bird Measurements" (PDF). The Condor. 27 (2): 59–61. doi:10.2307/1363054.

- Rising, JD & KM Somers. "The measurement of overall body size in birds" (PDF). The Auk. 106 (4): 666–674.

- Lougheed SC, Arnold TW, Bailey RC (1991). "Measurement Error of External and skeletal variables in birds and its effect on principal components" (PDF). 108 (2): 432–436. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rasmussen PC, Anderton JC (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Washington DC & Barcelona: Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. pp. 18–19.

- Borras A, Pascual J, Senar JC. "What do different bill measures measure and what is the best method to use in granivorous birds?" (PDF). J. Field Ornithol. 71 (4): 606–611.

- George A. Clark, Jr. (1979). "Body Weights of Birds: A Review" (PDF). The Condor. 81 (2): 193–202. doi:10.2307/1367288.