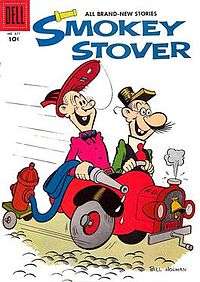

Bill Holman (cartoonist)

Bill Holman (March 22, 1903 – February 27, 1987)[1] was an American cartoonist who drew the classic comic strip Smokey Stover from 1935 until he retired in 1973. Distributed through the Chicago Tribune syndicate, it had the longest run of any strip in the screwball genre. Holman signed some strips with the pseudonym Scat H. He once described himself as "always inclined to humor and acting silly."[2]

| Bill Holman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 22, 1903 Crawfordsville, Indiana |

| Died | February 27, 1987 (aged 83) New York City, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist |

Notable works | Smokey Stover |

| Spouse(s) | Dolores |

| http://www.smokey-stover.com/ | |

Born in Crawfordsville, Indiana, Holman lived as a child in Nappanee, Indiana, a town where six successful cartoonists lived when they were children. Holman's father died when he was young. He began drawing when he was 12 years old.

While working part-time at Nappanee's local five and dime store, he developed an interest in art as a career and sent away for the Landon School of Illustration and Cartooning correspondence course.[3] Dropping out of high school, he was 15 when he moved with his mother to Chicago. There he took night courses at the Academy of Fine Arts and learned more about cartooning from Carl Ed.

In 1920, he held a job as a copy boy at the Chicago Tribune for six dollars a week. The position gave him the opportunity to hang out with the top Tribune cartoonists, including Sidney Smith, Harold Gray and E. C. Segar.

In Cleveland, he began working for the Newspaper Enterprise Association, which syndicated his short-lived animal strip, Billville Birds (1922). After three years with NEA and Scripps-Howard, he headed for New York, where he was a Herald Tribune staff artist and drew the child strip G. Whizz Jr. for the New York Herald Tribune Syndicate. He scored a success when he headed in a new direction, submitting his cartoons to a variety of different magazines, including Liberty, Redbook, Collier's and Life.[4][5]

Smokey Stover and Spooky

Holman thought firemen were funny, "running around in a red wagon with sirens and bells," and he began doing Smokey Stover as a Sunday strip for the Chicago Tribune Syndicate on March 10, 1935.[4]

One month later (April 7, 1935), to accompany Smokey Stover, he launched a topper strip, Spooky. With a perpetually bandaged tail, the firehouse cat Spooky lived with its owner, Fenwick Flooky, who did embroidery while sitting barefoot in a rocking chair.

The daily Smokey Stover was not launched until November 14, 1938. Holman loved word play, and all of his features percolated with puns.[2] In his file cabinet, Holman kept thousands of puns. Readers of Smokey Stover often sent him puns, sometimes with accompanying illustrations.[6]

He also inserted bizarre words and phrases, such as "Foo," "Notary Sojac," "Scramgravy Ain't Wavy" and "1506 Nix Nix". Some of these became national catchphrases. "1506 Nix Nix" was an inside joke on Holman's friend, cartoonist Al Posen, as Holman once explained, "The late Al Posen, who did the Sweeney and Son comic strip, was a bachelor living in a hotel room, number 1506. I began using the phrase, a private joke between the two of us, as a warning to girls to stay away from Al's room."[7]

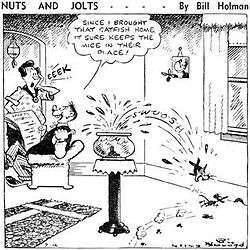

Nuts and Jolts

Holman's gag panel, Nuts and Jolts, was syndicated by the Chicago Tribune - New York News Syndicate from the 1930s to 1970. When Gaar Williams, who drew a gag panel under a variety of titles, died in 1935, Holman stepped in as a replacement. In July 1935, Holman picked up where Williams had left off, but the Nuts and Jolts title did not appear on the series until July 3, 1939. That same month, he began a Thursday panel, Zipper, about a dog.[8]

Journalist Al Meyers described Holman in a 1938 feature story:

We have often been buttonholed and asked, "What sort of guy is this Holman?" "Is he as nutty as his character Smokey?" Well, yes and no. He's of medium height, baldish and smiles like a Pepsodent advertisement. He wears conservative cut clothes with an Elk's head in his left lapel. In short, Holman is a ringer for the guy your older sister married. But it's his eyes that get you after a while. His left one practically laughs at you while you're talking to him. His right orb sparkles like that of a fugitive from the Creedmore State Hospital.[9]

By 1939, when Holman was earning $1500 a month, he gave a humorous summary of his life to Editor & Publisher:

To make a long Foo short, here is the dope, and I do mean me. I was born in the state of frenzy, but for present purposes let's make it Indiana. At an early age my father died, and I was sent out into the world to make a living for my mother, one cat with a sore tail, and no kitten. This all happened in Nappanee, Indiana. My first job was running a popcorn machine for the local dime store. This is considered excellent training for a comic artist and no doubt accounts for a certain corny touch which so many of my gags seem to have. At 16, I was working in the art department of the Chicago Tribune. Having lost my eraser, I realized I could afford to make no more mistakes, so Scripps-Howard made the next one and hired me. For the next two years, I drew no crowds but plenty of drawings. My strip act laid an egg, the art editor threw it at me, and I was on my way to New York. After seven years of itch and drawing a kid comic for the New York Herald Tribune, I entered the magazine field. The following five freelance years were happy and profitable. Hundreds of my drawings infested the pages of Collier's, Saturday Evening Post, Life, Judge and Everybody's Weekly of London. This work drew the attention of the Tribune-News Syndicate and I was asked to submit a Sunday feature. The outcome was Smokey Stover, Spooky, the cat, seven daily cartoons and Foo. I have always liked firemen. And now that I'm being paid to draw about their adventures, I can tell you I'm just crazy about them.[8]

For the USO, Holman made many trips abroad to entertain troops in the South Pacific, Europe, Japan and Korea, in addition to his chalk talks at veteran’s hospitals. A promoter of U.S. Savings Bonds, Holman donated his time to draw booklets for local fire-safety campaigns. He was also involved in numerous children’s charities.

Holman was one of the co-founders of the National Cartoonists Society, and he was the organization's president in 1961-62. He continued his close association with the Society after his 1973 retirement. Even after retiring from Smokey Stover, Holman could not stop the flow of puns and verbal/visual ideas, and he produced stack of sketches for a possible syndicated panel he titled Wall Nuts.[10] This had no connection with Gene Ahern's The Nut Bros: Ches and Wal, but it could be a nod to Ahern's strip which mined a vein of surreal silliness somewhat similar to Smokey Stover.

At age 83, Holman died February 27, 1987 in New York, survived by his wife Dolores.[1]

In Nappanee, Holman is cited on the Indiana Historical Bureau's Historical Marker, which reads:

Merrill Blosser was first Nappanee artist to gain national recognition as a professional cartoonist. Freckles and His Friends, his most popular cartoon, ran from 1915 to 1973, syndicated by Newspaper Enterprise Association. In 1965, National Cartoonists Society honored Blosser on fiftieth year of Freckles and its "wholesome entertainment. Five other Nappanee artists became nationally recognized cartoonists. Henry Maust and Francis "Mike" Parks drew newspaper editorial cartoons; Bill Holman's best was Smokey Stover (1935-1973); Fred Neher's Life’s Like That ran 1934-1977; Max Gwin drew Slim and Spud for Prairie Farmer 1955-1991. Town, training, and careers connected these artists.

Bibliography

According to Holman, more than 100,000 copies of Whitman's ten-cent Smokey Stover books were sold by 1939.[8]

- Smokey Stover: Fire Fighter of Foo. Better Little Book, Whitman Publishing, 1937.

- Smokey Stover and the Fire Chief of Foo. Better Little Book, Whitman Publishing Co., 1938.

- Smokey Stover: The Foo Fighter. Better Little Book, Whitman Publishing, 1938.

- Smokey Stover: The False Alarm Fireman. Better Little Book, Whitman Publishing, 1939.

- Smokey Stover, The Foolish Foo Fighter. Better Little Book, Whitman Publishing, 1945.

- Bill Holman's Smokey Stover, Book 1. Introduction by Harvey Kurtzman. Blackthorne, 1985.

See also

References

- "BILL HOLMAN," New York Times (March 21, 1987).

- Goulart, Ron, editor. The Encyclopedia of American Comics, Facts on File, 1990.

- Trickey, Erick. "Quick Draw," Cleveland Magazine, February 2009.

- Bill Holman

- Lambiek

- Brinkley, Bill. "Smokey Stover Creator Gets Rich Turning Hogs Into Gold," The Washington Post, October 5, 1949.

- Canemaker, John. "Bill Holman", Millimeter

- Schneider, Walter E. "Holman Renews Contract; To Do New Daily Panel," Editor & Publisher, July 8, 1939.

- Meyers, Al. "Smokey Stover Joins Daily Comics Brigade," November 1938.

- Mike Lynch Cartoons: "Unseen Bill Holman Comics"

Sources

- Strickler, Dave. Syndicated Comic Strips and Artists, 1924-1995: The Complete Index. Cambria, California: Comics Access, 1995. ISBN 0-9700077-0-1