Villa Bighi

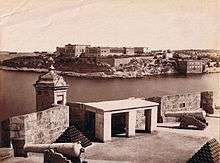

Royal Naval Hospital Bighi (RNH Bighi) also known as Bighi Hospital, was a major naval hospital located in the small town of Kalkara on the island of Malta. It was built on the site of the gardens of Palazzo Bichi,[1] that was periodically known as Palazzo Salvatore. RNH Bighi served the eastern Mediterranean in the 19th and 20th centuries and, in conjunction with the RN Memorial Hospital at Imtarfa, contributed to the nursing and medical care of casualties whenever hostilities occurred in the Mediterranean. The building is now known as Villa Bighi and it houses a restoration unit.

| Royal Naval Hospital Bighi | |

|---|---|

Bighi Hospital as seen from the Grand Harbour | |

| |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Kalkara, Malta |

| Coordinates | 35°53′35.1″N 14°31′28.2″E |

| Organisation | |

| Type | Military |

| Services | |

| Beds | 250 |

| History | |

| Opened | 29 September 1830 |

| Closed | 17 September 1970 |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in Malta |

History

Palazzo Bichi

On the site of the current building is Palazzo Bichi (now Palazzo Bighi)[2][3][4][5][6] also known as Villa Bichi, built in 1675 during the Order of St. John by Fra Giovanni Bichi on the designs of Lorenzo Gafa.[7] Fra Giovanni Bichi was the nephew of Pope Alexander VII.[2] The palace passed to his nephew Fra Mario Bichi, a member of the Order, even before it was finished as Fra Giovanni Bichi had died. He sold it to Bailiff Fra Giovanni Sigismondo, who was the Count of Schaesberg, in 1712. It was then known as Palazzo Salvatore and Gardens[8] because of the hill being named Salvatore Hill.[9]

The palace became known again as Palazzo Bichi after it was bought by another Fra Giovanni Bichi in 1712 and remained his until his death in 1740. The palace is said to have housed Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 before his entry in Valletta but this is disputed.[8] The building was used for quarantine for high officials during the rule of the Order of St John, such as by the Inquisitor Monsignor Paolo Passionei.[10]

Since the arrival of the British military in Malta it started to be known (since 1799) as Villa Bighi particularly because of the references to it by Sir Alexander Ball. Most palaces in Malta built by the Order started to be referred to as Villas by the British, and particularly the word Bichi of Villa Bichi was corrupted to Villa Bighi.[8] Even before his arrival, the site was chosen by Nelson to build a naval hospital since 1803.[11]

The palace, or villa, and its garden[1] become a public building of the Civil Government during the British Protectorate but was left to dilapidate. The building served as a cholera epidemic hospital in 1813-4.[12] It was only with the intervention of King George IV in 1827 when it was granted permission to develop the site of the gardens, and turn them in the present Bighi Hospital. This happened on the request of the Maltese governor Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby. The original villa, Villa Bichi, is today housing an educational center known as MCST.[8] Palazzo Bichi is scheduled as a Grade 1 national monument by the Malta Environment and Planning Authority.[2]

Villa Bighi

_04_ies.jpg)

In 1829 four Egyptian limestone stelae, that pre-date the Phoenician period in Malta, were found on the site by British archaeologists.[13][14] Phoenician remains bearing inscriptions were also found that are now displayed at the British Museum.[15] On the request of the British Royal Navy to the Governor the site was handed over in 1830 to build the Royal Navy Bighi Hospital. The building was designed by the eldest son of Saverio Scerri.[16] The building cost roughly £20,000 and started operating in 1832. It accommodated 200 beds and it roughly gave service to 800 navy sailors per year. The design of Bighi Hospital is generally attributed to Colonel (later Major General) Sir George Whitmore (1775–1862) who headed the Royal Engineers between 1811 and 1829. The foundation stone was laid by Vice Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm on 23 March 1830. The works were completed on 24 September 1832, at a total cost of £20,000. The West and East Wings' architecture is in the modern Doric style and built with high floors. The hospital has three separate building and are known as Villa Bighi. It should not be confused with Villa Bichi, built in 1675.[7] The Surgical (also known as the General Hospital Block) and the Zymotic Blocks were built in 1901 and 1903 respectively.

Service

Bighi Hospital contributed to the nursing and medical care of casualties whenever hostilities occurred in the Mediterranean, making Malta "the nurse of the Mediterranean".

The hospital's first director (1827–1844) was Dr John Liddell. He was later appointed director-general of the Royal Navy's Medical Department, and during his office Bighi nursed casualties from the Crimean War.

In 1863 the hospital looked after Queen Victoria's son Prince Alfred who was ill for a month with Typhoid Fever whilst serving as an officer in the RN. He recovered from his illness.[17] The Illustrated London News of 11 April 1863 included a detailed description of how the prince was quartered and the layout of the hospital.

During the First World War, RNH Bighi accommodated a very large number of casualties from the Daradanelles. During the Second World War, the Hospital was well within the target area of the heavy bombing since it was surrounded by military establishments. A number of its buildings were damaged or destroyed, including the x-ray theatre, the East and West Wings, the Villa and the Cot Lift from the Bighi Jetty to the Hospital. Among several Doctors and nurses of renown to serve here were Doris Beale DBE.

Closure and Subsequent Site Usage

In 1967, during the second rundown of the British services and their employees in Malta, Bighi Hospital was on the brink of closing down. On 17 September 1970 Bighi was closed down indefinitely.[18]

In 1977 parts of the building were occupied by the former Senglea Trade School while other sections accommodated a secondary school.

Since 2010 the site has housed the head office of Heritage Malta; the national agency for museums, conservation practice and cultural heritage.[19]

Further reading

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bighi hospital. |

- McGill, Thomas (1839). A hand book, or guide, for strangers visiting Malta. L. Tonna. pp. 77–78.

- "Palazzo Bighi". Times of Malta. 3 April 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "Palazzo Bichi". Google Search. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Azopardi, Giovanni (1 January 1836). "Giornale della presa di Malta e Grozo, dalla Republica francese, e della susseguente rivoluzione della campagna".

- Bonelli Conenna, L. (1990). Il Contrado Senese alla fine del XVII secolo – poderi, rendite e proprietari. Siena: Academia Senese degli Intronati. p. 76.

- "The 'Cabreo' of Fra Mario Bichi". The Malta Independent. 7 February 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "Military Hospitals of the Malta Garrison". British Army Medical Services and the Malta Garrison 1799–1979. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "History & Origins". Malta Council for Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 8 September 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "Bichi: Views from the Villa exhibition". Gozo News. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/handle/123456789/12775/Sanitary%20organization%20in%20Malta%20in%201743.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Savona-Ventura, Charles (6 December 2015). Knight Hospitaller Medicine in Malta 1530–1798. Lulu.com. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-326-48222-0.

- Attard, A. (2011). It-Tlett Ibliet fi żmien il-pesta. Programm tal-festa Marija Immakulata, Belt Cospicua, 2011: 425 sena Parroċċa, 1586-2011, 53-56.

- https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/49014/1/Lehen%20is-Sewwa_1975_09_20_Bonnici_Arturo_Il-forti%20Ricasoli%20u%20l%20-palazz%20Bichi.pdf

- Mifsud, Anton; Mifsud, Simon; Aguis Sultana, Chris; Savona Ventura, Charles (2001). Malta – Echoes of Plato's Island (2nd ed.). Balzan, Malta: The Prehistoric Society of Malta. p. 29. ISBN 99932-15-02-3.

- MacGill, Thomas (1839). A hand book, or guide, for strangers visiting Malta. Malta: Luigi Tonna. p. 79.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "200-year-old History in an old musty archive". The Malta Independent. 11 March 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Rushton, Alan R. (2008). Royal Maladies: Inherited Diseases in the Royal Houses of Europe. Trafford Publishing. p. 120. ISBN 9781425168100.

- Serracino, Joseph (6 January 2018). "Dawra kulturali mal-Port il-Kbir (4)" (PDF). Orizzont. p. 20.

- "Contact Us". Heritage Malta. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

.tiff.jpg)