Big bang adoption

Big bang adoption or direct changeover is the adoption type of the instant changeover, when everybody associated with the old system moves to the fully functioning new system on a given date.[1][2][3]

When a new system needs to be implemented in an organization, there are three different ways to adopt this new system: the big bang adoption, phased adoption and parallel adoption. In case of parallel adoption the old and the new system are running parallel, so all the users can get used to the new system, and meanwhile do their work using the old system. Phased adoption means that the adoption will happen in several phases, so after each phase the system is a little nearer to be fully adopted. With the big bang adoption, the switch between using the old system and using the new system happens at one single date, the so-called instant changeover of the system. Everybody starts to use the new system at the same date and the old system will not be used anymore from that moment on.

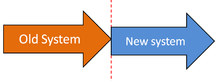

The big bang adoption type is riskier than other adoption types because there are fewer learning opportunities incorporated in the approach, so more preparation is needed to get to the big bang.[1] This preparation will be described below, illustrated by the process-data model of the big bang adoption.

Table of concepts

Several concepts are used in this entry. The definitions of these concepts are given in the table below to make the use of them clear.

| Concept | Definition |

| REPORT OF DETERMINED CHANGES | A report of the determination by the management of all the changes that will be executed to be able to implement the new system (Eason, 1988) |

| AGREEMENT CONTRACT | An understanding between individuals to follow a specific course of conduct (Wiktionary) |

| PLANNING | The management function that is concerned with defining goals for future organizational performance and deciding on the tasks and resources needed to be used in order to attain the said goals (Wikipedia) |

| CONVERTED DATA | Data which is converted from the old system to be able to fit in the new system (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003) |

| LOADED DATA | Converted data which is loaded in a new system (Eason, 1988) |

| TESTED DATA | Loaded data which is tested in the new system, to see whether it works or not (Eason, 1988) |

| TRIAL | A test, usually a test to see whether something does or does not meet a given standard (Wikipedia) |

| VALIDITY CHECK | Checked validity of the new database (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003) |

| DATABASE | A database is a collection of records stored in a computer in a systematic way, so that a computer program can consult it to answer questions. (Wikipedia) |

| APPLICATION | This is a loosely defined subclass of computer software that applies the capabilities of a computer directly to a task that the user wishes to perform (Wikipedia) |

| INFRASTRUCTURE | Infrastructure, most generally, is the set of interconnected structural elements that provide the framework for supporting the entire structure (Wikipedia) |

| LIST OF TRAINED USERS | List of trained users who are ready for the big bang to happen (Eason, 1988) |

| BUFFER | A buffer of experienced staff who can go into any office and take over the duties on a temporary basis so that the staff can plan the change, undergo training, etc.(Eason, 1988) |

| CONVERTED SYSTEM | Valid system containing tested data, checked by trials (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003; Eason, 1988) |

| RELEASED PART | All the different parts of the system that are released: the database, produced application and the infrastructure (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003) |

| RELEASE SYSTEM | The public release of a new version of a piece of software (Wikipedia) |

| NEW SYSTEM | System which is in use after the Big bang has happened, which replaces the former system (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003) |

Big bang

Once the management has decided to use the big bang method, and supports the changes which are needed for this, the real changing process can start. This process comprises several steps: converting the system, releasing parts of the system and training the future users.[1]

The activities in the process are explained in the table below, to state them clearly. The concepts that are used to execute the activities are in capitals.

| Activity | Subactivity | Description |

| Prepare management (see Adoption) | Determine organizational changes | The process of determining the changes that will have to take place to make the big bang possible that results in a REPORT OF ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGES |

| Agree on organizational changes | To be able to introduce the big bang, there has to be agreement about the change-plan which results in an AGREEMENT CONTRACT. If there's no agreement a new agreement meetings are necessary or the changes need to be determined different again and again, until an AGREEMENT CONTRACT is created. | |

| Convert system | Make planning for future users | Make the PLANNING for the people who will have to deal with the NEW SYSTEM, so they have an overview of the events that are going to happen[1] |

| Convert data from old system | Convert data from the old system so it can be used in the NEW SYSTEM (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003) | |

| Load data into new system | Load data the CONVERTED DATA into the NEW SYSTEM[1] | |

| Test data in new system | TEST DATA so it'll be known whether if the data will be usable in the NEW SYSTEM[1] | |

| Execute offline trials | Execute TRIAL with the system and with the users of the system to check whether if the system will work correct[1] | |

| Check to verify validity | Checking validity so the system can be made ready to become released (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003) | |

| Release parts | Release converted database | Release DATABASE which is converted from the old DATABASE[1] |

| Release produced application | Release the APPLICATION which is produced for the staff[1] | |

| Release infrastructure | Release the new INFRASTRUCTURE[1] | |

| Prepare users | Maintain buffer of experienced staff | Create a BUFFER of staff who can take over the duties of the people who have to be trained in using the NEW SYSTEM, so the daily work can go on[1] |

| Train users | Train users in preparation for the big release of the system, to create a LIST OF TRAINED USERS |

Convert the system

At first, a planning for the whole adoption process is needed. Making a planning allows future users to know what will happen and when they should expect certain changes, which avoids unnecessary uncertainties and therefore creates a better working atmosphere. The planning also makes clear when the real adoption takes place and gives the future users the opportunity to get ready for this change.[1] The model below shows that the activities (in the grey box) lead to outcomes (in the boxes next to the grey box) to be able to have a partial outcome: the converted system

When the planning is made and everyone knows what is expected from them, the technical changeover can start. First the old data needs to be converted into a form which is able to work with the data in the new system (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003). Then this data needs to be loaded into the new system, which results in the so-called loaded data. This loaded data needs to be tested to check the efficiency of the data and to test the level of understanding of the future users. Off-line trials need to be executed to check whether the system and the users can work together. Not only do the efficiency and the understanding need to be tested, but the validity needs to be tested to make the level of data validation clear.[1] ). If the data is not valid, the management need to determine the changes again and the organisation will have to prepare a different way of executing the Big bang adoption (See Adoption; Prepare an organization for adoption).

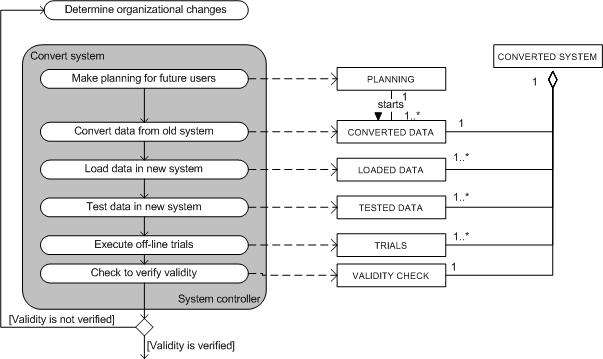

Release parts of the system

If all the data is valid, separate parts of the system can be released. The database which is converted from the old database needs to be released, so the new data is accessible. Next, the produced application needs to be released, so the new application can also be used. The infrastructure of the whole new system also needs to be released, so that it is clear what the system will look like and how everything is connected (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003). Important to note is that in this phase only separate parts are released, which don't form the new system yet, but only parts of it. Note that all of this happens off-line: only the system developers see this, the users are still working on the old system. The model above shows what activities need to be executed (in the grey box) by the system controller, to get the outcomes that lead to the released parts. If the release of the parts failed, the management need to determine new changes again (See Adoption; Prepare an organization for adoption).

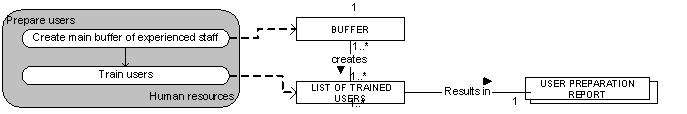

Train the organization in using the system

If the release of the separate parts succeeded, the next step can be taken: prepare the users. To be able to introduce the whole new system, i.e. to adopt it, all users need to be trained in working with the new system. Without huge consequences for the production level of an organization, training everyone is only possible if there is a buffer of experienced staff who can take over the daily work of the users that need to be trained. This means that for all the people that need to be trained, there will be staff available who can take over the work, so there won't be an enormous delay of work. When this buffer is created, the users can be trained .[1] The human resources department will create the buffer of experienced staff (activity in the grey box) by inviting applicants for the buffer. Then the users can be trained and the trained users can be listed, so a user preparation report can be written.

But training the future users properly is not as easy as it seems, as the FoxMeyer case illustrates (Scott, Vessey, 2000). This company used the big bang method to implement an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system. Wrong trainings were given, the assumption was made that users already knew enough about it and wrong skills were taught. Dow Corning also had big problems with acquiring the necessary skills during their big bang ERP implementation (Scott, Vessey, 2000). Using a new system demands various skills and knowledge, which in several cases seem to be underrated by the (change) managers.

Techniques

There are several techniques to implement a new system. The adoption phase is only one phase of the whole implementation. Regatta (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003) is for example a method which is developed to implements systems. This method, developed by Sogeti, treats a changeover as a project and focuses several stages of this project, for example the preparation phase (Regatta: preparation phase) of an adoption and on the acceptance of an implementation method (Regatta: adoption method). SAP Implementation is another technique specialized in implementing and adopting SAP AG software, which is divided into several techniques.

Risks

Because of the instant changeover, everything must be done in a fixed time schedule. This is a risky operation. The organization might not be ready yet for this, an incorrect dataset might be used, or the information system can get stuck, because of a lack of experience and start up problems. Also an incapable fall-back method can be a risk in implementing a system using the Big Bang (Koop, Rooimans and de Theye, 2003).

UK stock market, 1980s

The 1986 the London Stock Exchange closed on Friday night and the computers were all switched on the following Monday morning.[4][5] It has been alleged that this caused large losses.

Dow Corning

Dow Corning formerly used systems that were focused on specific departments. The management decided that they wanted to become a truly global company, that would use only one information system: an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)-system. To adopt this new ERP-system, they used the big bang adoption type and they spent considerable time and effort reexamining its business processes. The company was prepared for the adoption and first conducted three pilot implementations, before using the new system across the global organization. Second, FoxMeyer adopted an ERP-system with ambitious warehouse automation software, using the big bang adoption to gain competitive advantage. But FoxMeyer seemed to have an overoptimistic management with unrealistic expectations: the change was too big and too drastic. This resulted in very high work pressure to meet the deadlines for all the employees. So unrealistic expectations of the management are also a risk (Scott, Vessy, 2000).

Dow Corning monitored the progress constantly and made decisions to make sure that the deadlines would be met. This was only possible with feedback and good communication. FoxMeyer failed in having communication and attention that was necessary to be able to give fast and effective feedback. They instead tried to minimize problems by ignoring them, and gave discouraging criticism, which resulted in ambiguous feedback. This hindered organizational learning, something which is very important during an organizational change. So bad communication and ambiguous feedback are also risks when adopting a system with the big bang (Scott, Vessey, 2000).

Another risky strategy is to focus only on the outcome, not on how to achieve this outcome and underrating the learning process for users. It is very hard to plan learning or knowledge, though these are necessary to be able to execute the big bang changeover.

See also

References

- (Eason, 1988)

- Copley, Steve. "IGCSE ICT". Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Wainwright, Stewart (2009). IGSCE and O Level Computer Studies and Information Technology. Cambridge University Press. p. 29.

- "How technology has influenced The Stock Market. – Computers in the City". www.citc.it. 18 September 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- http://www.londonstockexchange.com/products-and-services/rns/history/history.htm

- Eason, K. (1988) Information technology and organizational change, Taylor & Francis.

- Koop, R., Rooimans R., and de Theye, M. (2003) Regatta: ICT-implementaties als uitdaging voor een vier-met-stuurman, S.D.U. Uitgeverij. ISBN 90-440-0575-8.

- Scott, J.E., Vessey, I. (2000) Implementing enterprise resource planning systems: the role of learning from failure, Information systems frontiers, vol.2(2), pp. 213–232.