Benignus of Dijon

Saint Benignus of Dijon (French: Saint Bénigne) was a martyr honored as the patron saint and first herald of Christianity of Dijon, Burgundy (Roman Divio). His feast falls, with All Saints, on November 1; his name stands under this date in the Martyrology of St. Jerome.[1]

Saint Benignus of Dijon | |

|---|---|

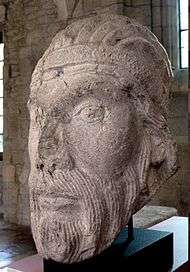

Early Romanesque head of Benignus of Dijon. Archaeological museum of Dijon. | |

| Bishop and martyr | |

| Born | trad. 3rd century Smyrna |

| Died | trad. 3rd century Burgundy |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Basilica of Saint Bénigne, Dijon |

| Feast | November 1 |

| Attributes | dog, key |

| Patronage | Dijon |

Life

No particulars concerning the person and life of Benignus were known at Dijon.[2] He may have been a missionary priest from Lyon, martyred at Epagny near Dijon. Johann Peter Kirsch says, "For some unknown reason his death is placed in the persecution under Aurelian (270-275)."[3]

According to Gregory of Tours the common people reverenced his grave, but Gregory's great-grandfather,[4] Saint Gregory, bishop of Langres (507–539/40), wished to put an end to this veneration, because he believed the grave to belong to a heathen. However, when he learned through a vision one night that the burial spot (in a large necropolis outside the Roman city) was in fact the previously overlooked grave of the holy martyr Benignus, the bishop had the tomb in which the sarcophagus lay restored, and he built a basilica over it.[3]

Saint Benignus' Abbey developed at the site and joined the Cluniac order. In the early eleventh century a larger church was built by its abbot William of Volpiano (died 1031). The abbey church built by Gregory of Langres was superseded by a Romanesque basilica, which collapsed in 1272 and was replaced by the present Dijon cathedral, dedicated to Benignus, where the shrine survived an earthquake in 1280 and the French Revolution. His purported sarcophagus can still be seen in the crypt.

The Passio of Saint Benignus

According to the sixth-century Passio Sancti Benigni, Benignus was a native of Smyrna. Polycarp of Smyrna had a vision of Saint Irenaeus, already dead,[5] in response to which he sent Benignus, as well as two priests and a deacon, to preach the Gospel in Gaul. They were shipwrecked on Corsica but managed to make their way to Marseilles. They made their way up the Rhone River and the Saône. Reaching Autun, they converted Symphorianus, son of the noble Faustus; Symphorianus was later martyred for his faith as Saint Symphorian.

Benignus, now on his own, proselytized openly in different parts of Gaul, and performed numerous miracles despite the persecution of Christians. Denounced to the Emperor Aurelian,[6] he was arrested at Épagny and put on trial. Benignus refused to sacrifice to pagan deities or to Caesar, and refused to deny Christ. The authorities savagely tortured him, to which he responded with new miracles; he did not change his mind. Eventually, Benignus was clubbed to death with a bar of iron and his heart pierced. "He was buried in a tomb which was made to look like a pagan monument in order to deceive the persecutors".[7]

Critique

In the time of Gregory of Tours[8] there was a sudden appearance of acta regarding Benignus, narrating the martyrdom of the saint, and said by Gregory to have been brought from Italy to Dijon by a pilgrim, but apparently edited at Dijon in the sixth century.[9]

According to these hagiographic accounts, Polycarp of Smyrna (died ca 155) had sent Benignus as a missionary to Dijon, where he had labored as a priest and had finally died a martyr, during the persecution under Aurelian (270–275), a possibility chronologically irreconcilable. Louis Duchesne[10] has proved that these acta are at the head of a whole group of legends which arose in the early years of the sixth century and were intended to demonstrate the early the beginnings of Christianity in the cities of that region (Besançon, Autun, Langres, Valence). "They are historically unreliable, and the very existence of some of the martyrs connected with these places is doubtful."[7] Kirsch says, "They are all falsifications by the same hand and possess no historical value."[3]

Attributes

On the seal of the abbey, Benignus of Dijon is depicted as having a dog by his side. He also holds a key.

References

- Ed. Rossi-Duchesne; cf. Acta Sanctorum, November, I, 138.

- "Although his nationality is doubtful and little seems to have been known about him locally, St Benignus was traditionally held to have spread the gospel throughout Burgundy" (Alban Butler) Sarah Fawcett Thomas, David Hugh Farmer, Paul Burns, eds. Butler's Lives of the Saints, First Full Edition: November, (1997) s.v. "1: St. Benignus of Dijon, Martyr (?Third Century)", p 2f.

- Kirsch, Johann Peter. "St. Benignus of Dijon." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 24 May 2018

- Butler 1997

- Butler 1997 points out that the historical Irenaeus of Lyon outlived Polycarp by fifty years.

- Butler 1997 notes that Aurelian did in fact visit Gaul, "but not until about one hundred years after the death of St Polycarp".

- Butler 1997.

- Gregory, De gloriâ martyrum, I, li.

- "undoubtedly spurious", Butler 1997; the Passio is published in Migne, Patrologia Latina, LXXI, 752.

- Duchesne, Fastes épiscopaux de l'ancienne Gaule, I, pp 51–62, noted in Butler 1997.

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benignus of Dijon. |

- Saint of the Day, November 1: Benignus of Dijon at SaintPatrickDC.org

- Wooden statue of St. Benignus of Dijon