Beam emittance

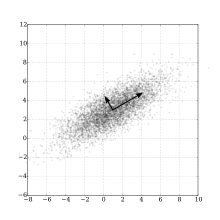

Emittance is a property of a charged particle beam in a particle accelerator. It is a measure for the average spread of particle coordinates in position-and-momentum phase space and has the dimension of length (e.g., meters) or length times angle (meters times radians). As a particle beam propagates along magnets and other beam-manipulating components of an accelerator, the position spread may change, but in a way that does not change the emittance. If the distribution over phase space is represented as a cloud in a plot (see figure), emittance is the area of the cloud. A more exact definition handles the fuzzy borders of the cloud and the case of a cloud that does not have an elliptical shape.

A low-emittance particle beam is a beam where the particles are confined to a small distance and have nearly the same momentum. A beam transport system will only allow particles that are close to its design momentum, and of course they have to fit through the beam pipe and magnets that make up the system. In a colliding beam accelerator, keeping the emittance small means that the likelihood of particle interactions will be greater resulting in higher luminosity. In a synchrotron light source, low emittance means that the resulting x-ray beam will be small, and result in higher brightness.

Definition

Emittance has units of length, but is usually referred to as "length × angle", for example, "millimeter × milli-radians". It can be measured in all three spatial dimensions. The dimension parallel to the motion of the particle is called the longitudinal emittance and the other two dimensions are referred to as the transverse emittances.

The arithmetic definition of a transverse emittance is:

Where:

- width is the width of the particle beam

- dp/p is the momentum spread of the particle beam

- D is the value of the dispersion function at the measurement point in the particle accelerator

- B is the value of the beta function at the measurement point in the particle accelerator

Since it is difficult to measure the full width of the beam, either the RMS width of the beam or the value of the width that encompasses a specific percentage of the beam (for example 95%) is measured. The emittance from these width measurements is then referred to as the "RMS emittance" or the "95% emittance", respectively.

One should distinguish the emittance of a single particle from that of the whole beam. The emittance of a single particle is the value of the invariant quantity

where x and x′ are the position and angle of the particle respectively and are the Twiss parameters. (In the context of Hamiltonian dynamics, one should be more careful to formulate in terms of a transverse momentum instead of x′.) This is the single particle emittance. In the case of a distribution of particles, one can define the RMS (root mean square) emittance as the RMS value of this quantity. The Gaussian case is typical, and the term emittance in fact often refers to the RMS emittance for a Gaussian beam.

Emittance of electrons versus heavy particles

To understand why the RMS emittance takes on a particular value in a storage ring, one needs to distinguish between electron storage rings and storage rings with heavier particles (such as protons). In an electron storage ring, radiation is an important effect, whereas when other particles are stored, it is typically a small effect. When radiation is important, the particles undergo radiation damping (which slowly decreases emittance turn after turn) and quantum excitation causing diffusion which leads to an equilibrium emittance.[1] When no radiation is present, the emittances remain constant (apart from impedance effects and intrabeam scattering). In this case, the emittance is determined by the initial particle distribution. In particular if one injects a "small" emittance, it remains small, whereas if one injects a "large" emittance, it remains large.

Acceptance

The acceptance, also called admittance,[2] is the maximum emittance that a beam transport system or analysing system is able to transmit. This is the size of the chamber transformed into phase space and does not suffer from the ambiguities of the definition of beam emittance.

Conservation of emittance

Lenses can focus a beam, reducing its size in one transverse dimension while increasing its angular spread, but cannot change the total emittance. This is a result of Liouville's theorem. Ways of reducing the beam emittance include radiation damping, stochastic cooling, and electron cooling.

Normalized emittance

The emittance so far discussed is inversely proportional to the beam momentum; increasing the momentum of the beam reduces the emittance and hence the physical size of the beam. This reduction is called adiabatic damping. It is often more useful to consider the normalized emittance:[3]

where β and γ are the relativistic functions. The normalized emittance does not change as a function of energy and so can track beam degradation if the particles are accelerated. If β is close to one then the emittance is approximately inversely proportional to the energy and so the physical width of the beam will vary inversely to the square root of the energy.

Emittance and brightness

Emittance is also related to the brightness of the beam. In microscopy brightness is very often used, because it includes the current in the beam and most systems are circularly symmetric.

with

See also

References

- http://www.slac.stanford.edu/pubs/slacreports/slac-r-121.html Archived 2015-05-11 at the Wayback Machine The Physics of Electron Storage Rings: An Introduction by Matt Sands

- Lee, Shyh-Yuan (1999). Accelerator physics. World Scientific. ISBN 978-9810237097.

- Wilson, Edmund (2001). An Introduction To Particle Accelerators. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198520542.