Baumol's cost disease

Baumol's cost disease (or the Baumol effect) is the rise of salaries in jobs that have experienced no or low increase of labor productivity, in response to rising salaries in other jobs that have experienced higher labor productivity growth. This pattern seemingly goes against the theory in classical economics in which real wage growth is closely tied to labor productivity changes. The phenomenon was described by William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen in the 1960s.[1]

The rise of wages in jobs without productivity gains is from the requirement to compete for employees with jobs that have experienced gains and so can naturally pay higher salaries, just as classical economics predicts. For instance, if the retail sector pays its managers 19th-century-style salaries, the managers may decide to quit to get a job at an automobile factory, where salaries are higher because of high labor productivity. Thus, managers' salaries are increased not by labor productivity increases in the retail sector but by productivity and corresponding wage increases in other industries.

Description

The original study was conducted for the performing arts sector.[1] Baumol and Bowen pointed out that the same number of musicians is needed to play a Beethoven string quartet today as was needed in the 19th century; the productivity of classical music performance has not increased. On the other hand, the real wages of musicians (as in all other professions) have increased greatly since the 19th century.

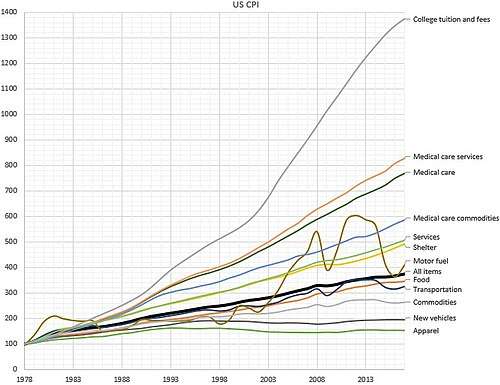

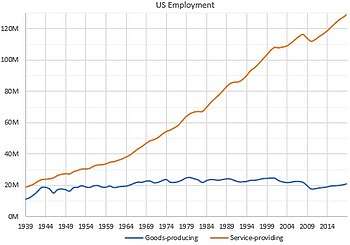

Baumol's cost disease is often used to describe consequences of the lack of growth in productivity in the quaternary sector of the economy and public services, such as public hospitals and state colleges. Labor-intensive sectors that rely heavily on non-routine human interaction or activities, such as health care, education, or the performing arts, have had less growth in productivity over time. As with the string quartet example, it takes nurses the same amount of time to change a bandage or college professors the same amount of time to mark an essay today as it did in 1966, as those types of activities rely on the movements of the human body, which cannot yet be engineered to perform more quickly, accurately, or efficiently in the same way that a machine, such as a computer, have. In contrast, goods-producing industries, such as the car manufacturing sector and other activities that involve routine tasks, workers are continually becoming more productive by technological innovations to their tools and equipment.[2]

Effects, symptoms, and remediation

Employers may react to cost increases in any number of ways including:

- Decrease quantity/supply

- Decrease quality

- Decrease profit margins, dividends, or investment

- Increase price

- Increase non-monetary compensation or employ volunteers

- Increase total factor productivity

In the case of education, the Baumol effect has been used as at least partial justification for the fact that, in recent decades, the price of college tuition has risen faster than the general rate of inflation.[3]

The reported productivity gains of the service industry in the late 1990s are largely attributable to total factor productivity.[4] Providers decreased the cost of ancillary labor through outsourcing or technology. Examples include offshoring data entry and bookkeeping for health care providers and replacing manually-marked essays in educational assessment with multiple choice tests that can be automatically marked.

The total factor productivity treatment is not available to the performing arts sector, as the consumable good is the labor itself. Instead, it has been observed that increases in price of the performing arts has been offset by increases in standard of living and entertainment spending by consumers.[5] The extent to which other treatments have been employed is subjective.

See also

References

- Baumol, William J.; Bowen, William G. (1966). Performing Arts, The Economic Dilemma: a study of problems common to theater, opera, music, and dance. Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press. ISBN 0262520117.

- Helland, Eric; Tabarrok, Alex (May 2019). "Why Are the Prices So Damn High?" (PDF). Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- Surowiecki, James (2011). "Debt by Degrees". The New Yorker.

- Bosworth, Barry P; Jack E Triplett (2003). "Productivity Measurement Issues in Services Industries: "Baumol's Disease" Has been Cured". The Brookings Institution.

- Heilbrun, James (2003). "Baumol's Cost Disease" (PDF). A handbook of cultural economics. Edward Elgar. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2011.

External links

- James Surowiecki (July 7, 2003). "What Ails Us". The New Yorker.

- Bill Hackos; Charles Dowdell. "Baumol's Disease - Is there a Cure?". Archived from the original on October 7, 2008.

- Charles Hugh Smith (December 11, 2010). "America's Economic Malady: A Bad Case of 'Baumol's Disease'". DailyFinance.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Sparviero, Sergio; Preston, Paschal (December 1, 2010). "Creativity and the Positive Reading of Baumol Cost Disease". The Service Industries Journal. 30 (12).

- Preston, Paschal; Sparviero, Sergio (December 30, 2009). "Creative Inputs as the Cause of Baumol's Cost Disease: The Example of Media Services". Journal of Media Economics. 22 (4): 239–252.