Battle of Nocera

The Battle of Nocera or Scafati was the first major battle of Roger II of Sicily and one of two of his major defeats (the other being the Battle of Rignano) at the hands of Count Ranulf of Alife.

| Battle of Nocera | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

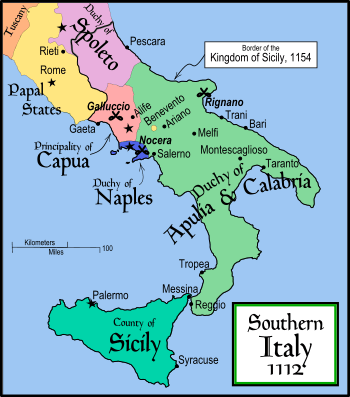

Southern Italy at the time of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Loyal Normans | Rebel Normans | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Roger II of Sicily |

Ranulf of Alife Robert II of Capua | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Background

In 1132, the disaffected Ranulf had garnered a large force with his ally, the prince of Capua, Robert II. The rebels massed outside of Benevento and that city, usually faithful to Roger, gave in. Roger, in shock, wheeled his army around and turned instead for Nocera, the greatest fortified city of the prince of Capua, other than Capua itself. The retreat over the Apennines was miraculously quick, but the rebels moved equally speedily to meet the royal army at Nocera, but Roger destroyed the sole bridge spanning the river Sarno. The rebels, with rapidity equally miraculous, constructed a temporary bridge and moved in on the Noceran siege.

Deployment

Roger raised his siege at the coming of the rebel army and Ranulf sent 250 knights ahead to the city walls to divert a fraction of the royal troops. The rebel army formed into two wings. Robert of Capua headed up the left wing and Ranulf the right. Each of the rebel wings was itself deployed into three divisions. Robert's divisions were formed in column, with mounted troops in the first and third lines, and foot soldiers in the second line. Ranulf formed his all-cavalry wing with his divisions in line. King Roger formed his army into eight divisions. These were deployed opposite Robert's wing in a column, that is, one division behind the other. The royal army, which included Muslim infantry, was said to have 3,000 cavalry and 40,000 infantry, "numbers which are certainly inflated."[1]

Having forced a crossing, the rebel army was "in a dangerous tactical position, for with the river at their backs, there would be scant possibility of an orderly retreat across the single bridge over the Sarno."[2]

Battle

On 24 July, a Roger initiated the engagement, charging the prince's knights. The royal troops broke Robert's first and second lines. The Capuan infantry retreated over the makeshift bridge, which collapsed and a thousand supposedly drowned. The Capuan third division held firm and counterattacked. By this time, the second royal division had been sent into the contest. Roger ordered a second charge, which was initially successful, pushing back the remaining Capuans.

At this moment, Ranulf joined the fray with 500 of the mounted men from his centre. He hit Roger's left flank and the royalists began to waver. Before reinforcements could be sent to help them, Ranulf had sent in his right and then his left divisions. The royal troops crumbled under the "successive shocks as they came into action."[3] Roger himself tried to inspire them, but they were already in retreat, the flight of the first two divisions having panicked the others. The king barely escaped to Salerno guarded by only four knights. The rebel victory was absolute.

Aftermath

Seven hundred knights and twenty-four loyalist barons were captured, along with the royal camp. The royal infantry suffered heavy losses in the rout. The booty was immense, according to both rebel-sympathising chroniclers, like Falco of Benevento, and royalists, like Henry, Bishop of Saint Agatha. Among the booty was the bull of Antipope Anacletus II granting Roger the royal title. The battle was of little long-term importance, however, because Pope Innocent II and Emperor Lothair II did not continue past Rome and so the rebels, without further assistance, lost many of their gains and were forced to surrender by July 1134.

Sources

- Falco of Benevento. Chronicon Beneventanum.

- Norwich, John Julius. The Kingdom in the Sun, 1130-1194. London: Longman, 1970.

- Beeler, John. Warfare in Feudal Europe, 730-1200. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 1971. ISBN 0-8014-9120-7

References

- Beeler, p 80

- Beeler, p 81

- Beeler, p 82