Battle of Gettysburg, second day

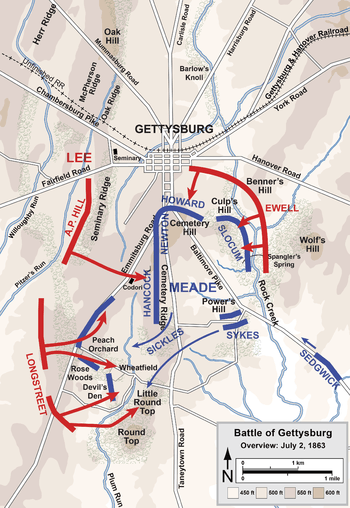

During the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg (July 2, 1863) Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee attempted to capitalize on his first day's success. His Army of Northern Virginia launched multiple attacks on the flanks of the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. The assaults were unsuccessful, and resulted in heavy casualties for both sides.

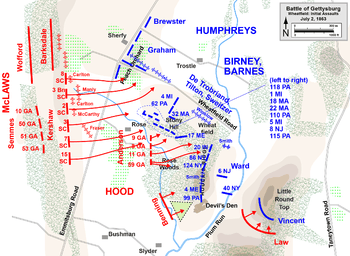

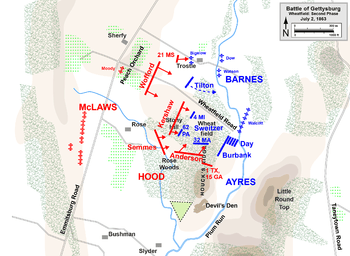

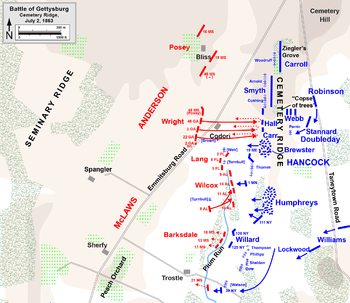

After a short delay to assemble his forces and avoid detection in his approach march, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet attacked with his First Corps against the Union left flank. His division under Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood attacked Little Round Top and Devil's Den. To Hood's left, Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws attacked the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard. Although neither prevailed, the Union III Corps was effectively destroyed as a combat organization as it attempted to defend a salient over too wide a front. Gen. Meade rushed as many as 20,000 reinforcements from elsewhere in his line to resist these fierce assaults. The attacks in this sector concluded with an unsuccessful assault by the Confederate Third Corps division of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson against the Union center on Cemetery Ridge.

That evening, Confederate Second Corps commander Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell turned demonstrations against the Union right flank into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and East Cemetery Hill, but both were repulsed.

The Union army had occupied strong defensive positions, and Meade handled his forces well, resulting in heavy losses for both sides, but leaving the disposition of forces on both sides essentially unchanged. Lee's hope of crushing the Army of the Potomac on Northern territory was dashed, but undaunted, he began to plan for the third day of fighting.

This article includes details of many attacks on the Union left flank (Devil's Den, the Wheatfield, and the Peach Orchard) and center (Cemetery Ridge), but separate articles describe other major engagements in this massive battle of the second day:

Background

Military situation

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Lee's plan and movement to battle

By the morning of July 2, six of the seven corps of the Army of the Potomac had arrived on the battlefield. The I Corps (Maj. Gen. John Newton, replacing Abner Doubleday) and the XI Corps (Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard) had fought hard on the first day, and they were joined that evening by the yet-unengaged troops of the XII Corps (Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum), III Corps (Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles), and II Corps (Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock), and on the morning of July 2 by the V Corps (Maj. Gen. George Sykes). The VI Corps (Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick) was still 30 miles (50 km) away in Manchester, Maryland, on that morning. They assumed positions in a fish hook shape about three miles (5 km ) long, from Culp's Hill, around to Cemetery Hill, and down the spine of Cemetery Ridge. The Army of Northern Virginia line was roughly parallel to the Union's, on Seminary Ridge and on an arc northwest, north, and northeast of the town of Gettysburg. All of the Second Corps (Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell) and Third Corps (Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill) were present, and the First Corps (Lt. Gen. James Longstreet) was arriving from Cashtown; only Longstreet's division under George E. Pickett did not participate in the battle on July 2.[1]

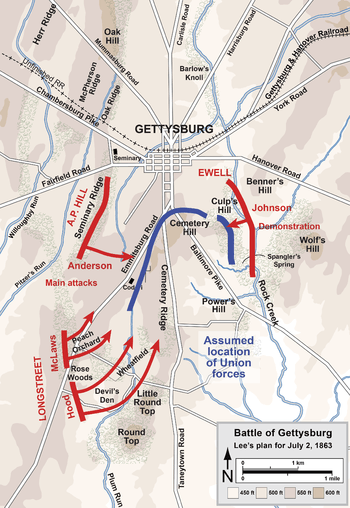

Robert E. Lee had several choices to consider for his next move. His order of the previous evening that Ewell occupy Culp's Hill or Cemetery Hill "if practicable" was not realized, and the Union army was now in strong defensive positions with compact interior lines. His senior subordinate, Longstreet, counseled a strategic move—the Army should leave its current position, swing around the Union left flank, and interpose itself on Meade's lines of communication, inviting an attack by Meade that could be received on advantageous ground. Longstreet argued that this was the entire point of the Gettysburg campaign, to move strategically into enemy territory but fight only defensive battles there. Lee rejected this argument because he was concerned about the morale of his soldiers having to give up the ground for which they fought so hard the day before. He wanted to retain the initiative and had a high degree of confidence in the ability of his army to succeed in any endeavor, an opinion bolstered by their spectacular victories the previous day and at Chancellorsville. He was therefore determined to attack on July 2.[2]

Lee wanted to seize the high ground south of Gettysburg, primarily Cemetery Hill, which dominated the town, the Union supply lines, and the road to Washington, D.C., and he believed an attack up the Emmitsburg Road would be the best approach. He desired an early-morning assault by Longstreet's Corps, reinforced by Ewell, who would move his Corps from its current location north of town to join Longstreet. Ewell protested this arrangement, claiming his men would be demoralized if forced to move from the ground they had captured.[3] And Longstreet protested that his division commanded by John Bell Hood had not arrived completely (and that Pickett's division had not arrived at all).[4] Lee compromised with his subordinates. Ewell would remain in place and conduct a demonstration (a minor diversionary attack) against Culp's Hill, pinning down the right flank of the Union defenders so that they could not reinforce their left, where Longstreet would launch the primary attack as soon as he was ready. Ewell's demonstration would be turned into a full-scale assault if the opportunity presented itself.[5]

Lee ordered Longstreet to launch a surprise attack with two divisions straddling, and guiding on, the Emmitsburg Road.[6] Hood's division would move up the eastern side of the road, Lafayette McLaws's the western side, each perpendicular to it. The objective was to strike the Union Army in an oblique attack, rolling up their left flank, collapsing the line of Union corps onto each other, and seizing Cemetery Hill.[7] The Third Corps division of Richard H. Anderson would join the attack against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge at the appropriate time. This plan was based on faulty intelligence because of the absence of J.E.B. Stuart and his cavalry, leaving Lee with an incomplete understanding of the position of his enemy. He believed that the left flank of the Union army was adjacent to the Emmitsburg Road hanging "in the air" (unsupported by any natural barrier), and an early morning scouting expedition seemed to confirm that.[8] In reality, by dawn of July 2 the Union line stretched the length of Cemetery Ridge and anchored at the foot of the imposing Little Round Top. Lee's plan was doomed from its conception, as Meade's line occupied only a small portion of the Emmitsburg Road near the town itself. Any force attacking up the road would find two entire Union corps and their guns posted on the ridge to their immediate right flank. By midday, however, Union general Sickles would change all that.[9]

Sickles repositions

When Sickles arrived with his III Corps, General Meade instructed him to take up a position on Cemetery Ridge that linked up with the II Corps on his right and anchored his left on Little Round Top. Sickles originally did so, but after noon he became concerned about a slightly higher piece of ground 0.7 miles (1,100 m) to his front, a peach orchard owned by the Sherfy family. He undoubtedly recalled the debacle at Chancellorsville, where the high ground ("Hazel Grove") he was forced to give up was used against him as a deadly Confederate artillery platform. Acting without authorization from Meade, Sickles marched his corps to occupy the peach orchard. This had two significant negative consequences: his position now took the form of a salient, which could be attacked from multiple sides; and he was forced to occupy lines that were much longer than his two-division corps could defend. Meade rode to the III Corps position and impatiently explained “General Sickles, this is neutral ground, our guns command it, as well as the enemy’s. The very reason you cannot hold it applies to them.” [10] Meade was furious about this insubordination, but it was too late to do anything about it—the Confederate attack was imminent.[11]

Longstreet delayed

Longstreet's attack was delayed, however, because he first had to wait for his final brigade (Evander M. Law's, Hood's division) to arrive, and then he was forced to march on a long, circuitous route that could not be seen by Union Army Signal Corps observers on Little Round Top. It was 4 p.m. by the time his two divisions reached their jumping off points, and then he and his generals were astonished to find the III Corps planted directly in front of them on the Emmitsburg Road. Hood argued with Longstreet that this new situation demanded a change in tactics; he wanted to swing around, below and behind, Round Top and hit the Union Army in the rear. Longstreet, however, refused to consider such a modification to Lee's order.[12]

Even so, and partly because of Sickles's unexpected location, Longstreet's assault did not proceed according to Lee's plan. Instead of wheeling left to join a simultaneous two-division push on either side of the Emmitsburg Road, Hood's division attacked in a more easterly direction than intended, and McLaws's and Anderson's divisions deployed brigade by brigade, in an en echelon style of attack, also heading more to the east than the intended northeast.[13]

Hood's assault

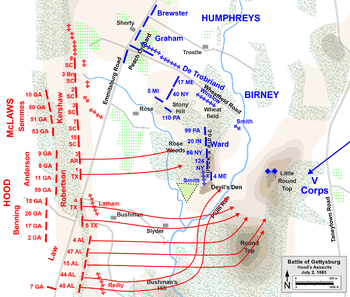

Longstreet's attack commenced with a 30-minute artillery barrage by 36 guns that was particularly punishing to the Union infantry in the Peach Orchard and the troops and batteries on Houck's Ridge. Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood's division deployed in Biesecker's Woods on Warfield Ridge (the southern extension of Seminary Ridge) in two lines of two brigades each: at the left front, Brig. Gen. Jerome B. Robertson's Texas Brigade (Hood's old unit); right front, Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law; left rear, Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson; right rear, Brig. Gen. Henry L. Benning.[14]

At 4:30 p.m., Hood stood in his stirrups at the front of the Texas Brigade and shouted, "Fix bayonets, my brave Texans! Forward and take those heights!" It is unclear to which heights he was referring. His orders were to cross the Emmitsburg Road and wheel left, moving north with his left flank guiding on the road. This discrepancy became a serious problem when, minutes later on Slyder's Lane, Hood was felled by an artillery shell bursting overhead, severely wounding his left arm and putting him out of action. His division moved ahead to the east, no longer under central control.[15]

There were four probable reasons for the deviation in the division's direction: first, regiments from the III Corps were unexpectedly in the Devil's Den area and they would threaten Hood's right flank if they were not dealt with; second, fire from the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters at Slyder's farm drew the attention of lead elements of Law's Brigade, moving in pursuit and drawing his brigade to the right; third, the terrain was rough and units naturally lost their parade-ground alignments; finally, Hood's senior subordinate, Gen. Law, was unaware that he was now in command of the division, so he could not exercise control.[16]

The two lead brigades split their advances into two directions, although not on brigade boundaries. The 1st Texas and 3rd Arkansas of Robertson's brigade and the 44th and 48th Alabama of Law's brigade headed in the direction of Devil's Den, while Law directed the remaining five regiments toward the Round Tops.[17]

Devil's Den

Devil's Den was located at the extreme left of the III Corps line, manned by the large brigade (six regiments and two companies of sharpshooters, 2,200 men in all) of Brigadier General J. H. Hobart Ward, in Maj. Gen. David B. Birney's division. It was the southern end of Houck's Ridge, a modest elevation on the northwest side of Plum Run Valley, made distinctive by piles of huge boulders. These boulders were not the direct avenue of approach used by the Confederates. The 3rd Arkansas and the 1st Texas drove through Rose Woods and hit Ward's line head-on. His troops had lacked the time or inclination to erect breastworks, and for over an hour both sides participated in a standup fight of unusual ferocity. In the first 30 minutes, the 20th Indiana lost more than half of its men. Its colonel, John Wheeler, was killed and its lieutenant colonel wounded. The 86th New York also lost its commander. The commander of the 3rd Arkansas fell wounded, one of 182 casualties in his regiment.[21]

Meanwhile, the two regiments from Law's brigade that had split from the column advancing to the Round Tops pushed up Plum Run Valley and threatened to turn Ward's flank. Their target was the 4th Maine and the 124th New York, defending the 4th New York Independent artillery battery commanded by Captain James Smith, whose fire was causing considerable disruption in Law's brigade's advance. The pressure grew great enough that Ward needed to call the 99th Pennsylvania from his far right to reinforce his left. The commander of the 124th New York, Colonel Augustus Van Horne Ellis, and his major, James Cromwell, decided to counterattack. They mounted their horses despite the protests of soldiers who urged them to lead more safely on foot. Maj. Cromwell said, "The men must see us today." They led the charge of their "Orange Blossoms" regiment to the west, down the slope of Houck's Ridge through a triangular field surrounded by a low stone fence, sending the 1st Texas reeling back 200 yards (180 m). But both Colonel Ellis and Major Cromwell were shot dead as the Texans rallied with a massed volley; and the New Yorkers retreated to their starting point, with only 100 survivors from the 283 they started with. As reinforcements from the 99th Pennsylvania arrived, Ward's brigade retook the crest.[22]

The second wave of Hood's assault was the brigades of Henry Benning and George "Tige" Anderson. They detected a gap in Birney's division line: to Ward's right, there was a considerable gap before the brigade of Régis de Trobriand began. Anderson's line smashed into Trobriand and the gap at the southern edge of the Wheatfield. Trobriand wrote that the Confederates "converged on me like an avalanche, but we piled all the dead and wounded men in our front." The Union defense was fierce, and Anderson's brigade pulled back; its commander was wounded in the leg and was carried from the battle.[23]

Two of Benning's Confederate regiments, the 2nd and 17th Georgia, moved down Plum Run Valley around Ward's flank. They received murderous fire from the 99th Pennsylvania and Hazlett's battery on Little Round Top, but they kept pushing forward. Capt. Smith's New York battery was under severe pressure from three sides, but its supporting infantry regiments were suffering severe casualties and could not protect it. Three 10-pound Parrott rifles were lost to the 1st Texas, and they were used against Union troops the next day.[24]

Birney scrambled to find reinforcements. He sent the 40th New York and 6th New Jersey from the Wheatfield into Plum Run Valley to block the approach into Ward's flank. They collided with Benning's and Law's men in rocky, broken ground that the survivors would remember as the "Slaughter Pen". (Plum Run itself was known as "Bloody Run"; Plum Run Valley as the "Valley of Death".) Col. Thomas W. Egan, commanding the 40th New York, was called on by Smith to recover his guns. The men of the "Mozart" regiment slammed into the 2nd and 17th Georgia regiments, with initial success. As Ward's line along Houck's Ridge continued to collapse, the position manned by the 40th became increasingly untenable. However, Egan pressed his regiment onward, according to Col. Wesley Hodges of the 17th Georgia, launching seven attacks against the Confederate positions within the boulders of Slaughter Pen and Devil's Den. As the men of the 40th fell back under relentless pressure, the 6th New Jersey covered their withdrawal and lost a third of its men in the process.[25]

The pressure on Ward's brigade was eventually too great, and he was forced to call for a retreat. Hood's division secured Devil's Den and the southern part of Houck's Ridge. The center of the fighting shifted to the northwest, to Rose Woods and the Wheatfield, while five regiments under Evander Law assaulted Little Round Top to the east. Benning's men spent the next 22 hours on Devil's Den, firing across the Valley of Death on Union troops massed on Little Round Top.[26]

Of 2,423 Union troops engaged, there were 821 casualties (138 killed, 548 wounded, 135 missing); the 5,525 Confederates lost 1,814 (329, 1,107, 378).[27]

Little Round Top

The Confederate assaults on Little Round Top were some of the most famous of the three-day battle and the Civil War. Arriving just as the Confederates approached, Col. Strong Vincent's brigade of the V Corps mounted a spirited defense of this position, the extreme left of the Union line, against furious assaults up the rocky slope. The stand of the 20th Maine under Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain against the 15th Alabama (Col. William C. Oates) is particularly storied, but heroes such as Strong Vincent, Patrick "Paddy" O'Rorke, and Charles E. Hazlett also made names for themselves.

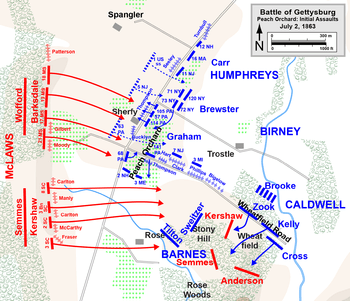

McLaws's assault

Lafayette McLaws arranged his division on Warfield Ridge similar to Hood's on his right—two lines of two brigades each: left front, facing the Peach Orchard, the brigade of Brig. Gen. William Barksdale; right front, Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw; left rear, Brig. Gen. William T. Wofford; right rear, Brig. Gen. Paul Jones Semmes.[28]

Lee's original plan called for Hood and McLaws to attack in concert, but Longstreet held back McLaws while Hood's attack progressed. Around 5 p.m., Longstreet saw that Hood's division was reaching its limits and that the enemy to its front was fully engaged. He ordered McLaws to send in Kershaw's brigade, with Barksdale's to follow on the left, beginning the en echelon attack—one brigade after another in sequence—that would be used for the rest of the afternoon's attack. McLaws resented Longstreet's hands-on management of his brigades. Those brigades engaged in some of the bloodiest fighting of the battle: the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard.[6]

Wheatfield

The area known as the Wheatfield had three geographic features, all owned by the John Rose family: the 20 acre (8 ha) field itself, Rose Woods bordering it on the west, and a modest elevation known as Stony Hill, also to the west. Immediately to the southeast was Houck's Ridge and to the south Devil's Den. The fighting here, consisting of numerous confusing attacks and counterattacks over two hours by eleven brigades, earned the field the nickname "Bloody Wheatfield."[29]

The first engagement in the Wheatfield was actually that of Anderson's brigade (Hood's division) attacking the 17th Maine of Trobriand's brigade, a spillover from Hood's attack on Houck's Ridge. Although under pressure and with its neighboring regiments on Stony Hill withdrawing, the 17th Maine held its position behind a low stone wall with the assistance of Winslow's battery, and Anderson fell back. Trobriand wrote, "I had never seen any men fight with equal obstinacy."[30]

By 5:30 p.m., when the first of Kershaw's regiments neared the Rose farmhouse, Stony Hill had been reinforced by two brigades of the 1st Division, V Corps, under Brig. Gen. James Barnes, those of Cols. William S. Tilton and Jacob B. Sweitzer. Kershaw's men placed great pressure on the 17th Maine, but it continued to hold. For some reason, however, Barnes withdrew his understrength division about 300 yards (270 m) to the north—without consultation with Birney's men—to a new position near the Wheatfield Road. Trobriand and the 17th Maine had to follow suit, and the Confederates seized Stony Hill and streamed into the Wheatfield. (Barnes's controversial decision was widely criticized after the battle, and it effectively ended his military career.)[32]

Earlier that afternoon, as Meade realized the folly of Sickles's movement, he ordered Hancock to send a division from the II Corps to reinforce the III Corps. Hancock sent the 1st Division under Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell from its reserve position behind Cemetery Ridge. It arrived at about 6 p.m. and three brigades, under Cols. Samuel K. Zook, Patrick Kelly (the Irish Brigade), and Edward E. Cross moved forward; the fourth brigade, under Col. John R. Brooke, was in reserve. Zook and Kelly drove the Confederates from Stony Hill, and Cross cleared the Wheatfield, pushing Kershaw's men back to the edge of Rose Woods. Both Zook and Cross were mortally wounded in leading their brigades through these assaults, as was Confederate Semmes. When Cross's men had exhausted their ammunition, Caldwell ordered Brooke to relieve them. By this time, however, the Union position in the Peach Orchard had collapsed (see next section), and Wofford's assault continued down the Wheatfield Road, taking Stony Hill and flanking the Union forces in the Wheatfield. Brooke's brigade in Rose Woods had to retreat in some disorder. Sweitzer's brigade was sent in to delay the Confederate assault, and they did this effectively in vicious hand-to-hand combat. The Wheatfield changed hands once again.[35]

Additional Union troops had arrived by this time. The 2nd Division of the V corps, under Brig. Gen. Romeyn B. Ayres, was known as the "Regular Division" because two of its three brigades were composed entirely of U.S. Army (regular army) troops, not state volunteers. (The brigade of volunteers, under Brig. Gen. Stephen H. Weed, was already engaged on Little Round Top, so only the regular army brigades arrived at the Wheatfield.) In their advance across the Valley of Death they had come under heavy fire from Confederate sharpshooters in Devil's Den. As the regulars advanced, the Confederates swarmed over Stony Hill and through Rose Woods, flanking the newly arrived brigades. The regulars retreated back to the relative safety of Little Round Top in good order, despite taking heavy casualties and pursuing Confederates. The two regular brigades suffered 829 casualties out of 2,613 engaged.[36]

This final Confederate assault through the Wheatfield continued past Houck's Ridge into the Valley of Death at about 7:30 p.m. The brigades of Anderson, Semmes, and Kershaw were exhausted from hours of combat in the summer heat and advanced east with units jumbled up together. Wofford's brigade followed to the left along the Wheatfield Road. As they reached the northern shoulder of Little Round Top, they were met with a counterattack from the 3rd Division (the Pennsylvania Reserves) of the V Corps, under Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford. The brigade of Col. William McCandless, including a company from the Gettysburg area, spearheaded the attack and drove the exhausted Confederates back beyond the Wheatfield to Stony Hill. Realizing that his troops were too far advanced and exposed, Crawford pulled the brigade back to the east edge of the Wheatfield.[37]

The bloody Wheatfield remained quiet for the rest of the battle. But it took a heavy toll on the men who traded possession back-and-forth. The Confederates had fought six brigades against 13 (somewhat smaller) Federal brigades, and of the 20,444 men engaged, about 30% were casualties. Some of the wounded managed to crawl to Plum Run but could not cross it. The river ran red with their blood. As with the Cornfield at Antietam, this small expanse of agricultural ground would be remembered by veterans as a name of unique significance in the history of warfare.[38]

Peach Orchard

While the right wing of Kershaw's brigade attacked into the Wheatfield, its left wing wheeled left to attack the Pennsylvania troops in the brigade of Brig. Gen. Charles K. Graham, the right flank of Birney's line, where 30 guns from the III Corps and the Artillery Reserve attempted to hold the sector. The South Carolinians were subjected to infantry volleys from the Peach Orchard and canister from all along the line. Suddenly someone unknown shouted a false command, and the attacking regiments turned to their right, toward the Wheatfield, which presented their left flank to the batteries. Kershaw later wrote, "Hundreds of the bravest and best men of Carolina fell, victims of this fatal blunder."[39]

Meanwhile, the two brigades on McLaws's left—Barksdale's in front and Wofford's behind—charged directly into the Peach Orchard, the point of the salient in Sickles's line. Gen. Barksdale led the charge on horseback, long hair flowing in the wind, sword waving in the air. Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys's division had only about 1,000 men to cover the 500 yards (460 m) from the Peach Orchard northward along the Emmitsburg Road to the lane leading to the Abraham Trostle farm. Some were still facing south, from where they had been firing on Kershaw's brigade, so they were hit in their vulnerable flank. Barksdale's 1,600 Mississippians wheeled left against the flank of Humphreys's division, collapsing their line, regiment by regiment. Graham's brigade retreated back toward Cemetery Ridge; Graham had two horses shot out from under him. He was hit by a shell fragment, and by a bullet in his upper body. He was eventually captured by the 21st Mississippi. Wofford's men dealt with the defenders of the orchard.[40]

As Barksdale's men pushed toward Sickles's headquarters near the Trostle barn, the general and his staff began to move to the rear, when a cannonball caught Sickles in the right leg. He was carried off in a stretcher, sitting up and puffing on his cigar, attempting to encourage his men. That evening his leg was amputated, and he returned to Washington, D.C. Gen. Birney assumed command of the III Corps, which was soon rendered ineffective as a fighting force.[41]

The relentless infantry charges posed extreme danger to the Union artillery batteries in the orchard and on the Wheatfield Road, and they were forced to withdraw under pressure. The six Napoleons of Capt. John Bigelow's 9th Massachusetts Light Artillery, on the left of the line, "retired by prolonge," a technique rarely used in which the cannon was dragged backwards as it fired rapidly, the movement aided by the gun's recoil. By the time they reached the Trostle house, they were told to hold the position to cover the infantry retreat, but they were eventually overrun by troops of the 21st Mississippi, who captured three of their guns.[42]

Humphreys's fate was sealed when the Confederate en echelon attack continued and his front and right flank began to be assaulted by the Third Corps division of Richard H. Anderson on Cemetery Ridge.

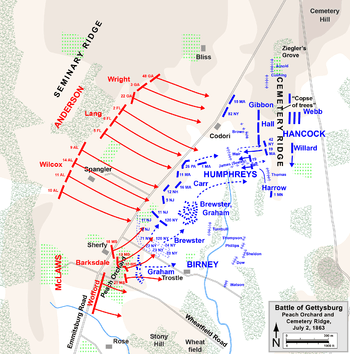

Anderson's assault

The remaining portion of the en echelon attack was the responsibility of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson's division of A.P. Hill's Third Corps, and he attacked starting at about 6 p.m. with five brigades in line, commencing on the right with Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox, followed by Perry's Brigade (commanded by Col. David Lang), Brig. Gen. Ambrose R. Wright, Brig. Gen. Carnot Posey, and Brig. Gen. William Mahone.[43]

The brigades of Wilcox and Lang hit the front and right flank of Humphreys's line, dooming any chance for his division to maintain its position on the Emmitsburg Road and completing the collapse of the III Corps. Humphrey displayed considerable bravery during the attack, leading his men from horseback and forcing them to maintain good order during their withdrawal. He wrote to his wife, "Twenty times did I [bring] my men to a halt and face about ... forcing the men to it."[44]

On Cemetery Ridge, Generals Meade and Hancock were scrambling to find reinforcements. Meade had sent virtually all of his available troops (including most of the XII Corps, who would be needed momentarily on Culp's Hill) to his left flank to counter Longstreet's assault, leaving the center of his line relatively weak. There was insufficient infantry on Cemetery Ridge and only a few artillery pieces, rallied from the debacle of the Peach Orchard by Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery.[45]

The long march from Seminary Ridge had left some of the Southern units disorganized, and their commanders paused momentarily at Plum Run to reorganize. Hancock led the II Corps brigade of Col. George L. Willard to meet Barksdale's brigade as it moved toward the ridge. Willard's New Yorkers drove the Mississippians back to Emmitsburg Road. Barksdale was wounded in his left knee, followed by a cannonball to his left foot, and finally was hit by another bullet to his chest, knocking him off his horse. His troops were forced to leave him for dead on the field, and he died the next morning in a Union field hospital. Willard was also killed, and Confederate guns drove back Willard's men in turn.[46]

As Hancock rode north to find additional reinforcements, he saw Wilcox's brigade nearing the base of the ridge, aiming at a gap in the Union line. The timing was critical, and Hancock chose the only troops at hand, the men of the 1st Minnesota, Harrow's Brigade, of the 2nd Division of the II Corps. They were originally placed there to guard Thomas's U.S. Battery. He pointed to a Confederate flag over the advancing line and shouted to Col. William Colvill, "Advance, Colonel, and take those colors!" The 262 Minnesotans charged the Alabama brigade with bayonets fixed, and they blunted their advance at Plum Run but at horrible cost—215 casualties (82%), including 40 deaths or mortal wounds, one of the largest regimental single-action losses of the war. Despite overwhelming Confederate numbers, the small 1st Minnesota, with the support of Willard's brigade on their left, checked Wilcox's advance and the Alabamians were forced to withdraw.[47]

The third Confederate brigade in line, under Ambrose Wright, crushed two regiments posted on the Emmitsburg Road north of the Codori farm, captured the guns of two batteries, and advanced toward a gap in the Union line just south of the Copse of Trees. (For a time, the only Union soldiers in this part of the line were Gen. Meade and some of his staff officers.) Wright's Georgia brigade may have reached the crest of Cemetery Ridge and beyond. Many historians have been skeptical of Wright's claims in his after-action report, which, if correct, would mean he passed the crest of the ridge and got as far as the Widow Leister's house before being struck in the flank and repulsed by Union reinforcements (Brig. Gen. George J. Stannard's Vermont brigade). Others believe his account was plausible because he accurately described the masses of Union troops on the Baltimore Pike that would have been invisible to him if he had been stopped earlier. Furthermore, his conversations with General Lee that evening lend support to his claim. It is possible that Lee derived some false confidence from Wright about the ability of his men to reach Cemetery Ridge the following day in Pickett's Charge.[48]

Wright told Lee that it was relatively easy to get to the crest, but it was difficult to stay there.[49] A significant reason Wright could not stay was his lack of support. Two brigades were on Wright's left and could have reinforced his success. Carnot Posey's brigade made slow progress and never crossed the Emmitsburg Road, despite protestations from Wright. William Mahone's brigade inexplicably never moved at all. Gen. Anderson sent a messenger with orders to Mahone to advance, but Mahone refused. Part of the blame for the failure of Wright's assault must lie with Anderson, who took little active part in directing his division in battle.[50]

Battle of East Cemetery Hill

Lee ordered Lt. Gen. Ewell to launch a demonstration, or minor diversionary attack, on the Union right flank. He started the attack at 4 p.m. with an artillery bombardment from Benner's Hill, which caused little damage to the Union lines, but the counterbattery fire returned upon the lower hill was deadly. Ewell's best artillery officer, 19-year-old Joseph W. Latimer, the "Boy Major", was mortally wounded, eventually dying a month later. Ewell did not launch a conventional infantry attack until after 7 p.m., after Anderson's assault on Cemetery Ridge had crested.[51] At around 8 p.m., two brigades of Jubal Early's division reached the Union artillery of East Cemetery Hill near the Baltimore Pike, but Union reinforcements drove them from the hill.[52]

Culp's Hill

Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's Confederate division attacked Brig. Gen. George S. Greene's XII Corps brigade behind strong breastworks on Culp's Hill. The Confederates suffered severe casualties and gained only the portions of the Union line that had been vacated under orders that afternoon by General Meade to reinforce the left flank of his line against Longstreet.[53]

Council of war

The battlefield fell silent around 10:30 p.m., except for the cries of the wounded and dying. Gen. Meade telegraphed to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck in Washington:[54]

The enemy attacked me about 4 p.m. this day and, after one of the severest contests of the war, was repulsed at all points. ... I shall remain in my present position to-morrow, but am not prepared to say, until better advised of the condition of the army, whether my operations will be of an offensive or defensive character.

— George G. Meade, Telegraph to Halleck, July 2, 1863

Meade made his decision late that night in a council of war that included his senior staff officers and corps commanders. The assembled officers agreed that, despite the beating the army took, it was advisable for the army to remain in its present position and to await attack by the enemy, although there was some disagreement about how long to wait if Lee chose not to attack. There is some evidence that Meade had already decided this issue and was using the meeting not as a formal council of war, but as a way to achieve consensus among officers he had commanded for less than a week. As the meeting broke up, Meade took aside Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, in command of the II Corps, and predicted, "If Lee attacks tomorrow, it will be in your front. ... he has made attacks on both our flanks and failed and if he concludes to try it again, it will be on our centre."[55]

There was considerably less confidence in Confederate headquarters that night. The army had suffered a significant defeat by not dislodging their enemy. A staff officer remarked that Lee was "not in good humor over the miscarriage of his plans and his orders." But in Lee's report, he showed more optimism:[56]

The result of this day's operations induce the belief that, with proper concert of action, and with the increased support that the positions gained on the right would enable the artillery to render the assaulting columns, we should ultimately succeed, and it was accordingly determined to continue the attack. ... The general plan was unchanged.

— Robert E. Lee, Official Report on battle, January 1864.

Years later, Longstreet would write that his troops on the second day had done the "best three hours' fighting done by any troops on any battle-field."[57] That night he continued to advocate for a strategic movement around the Union left flank, but Lee would hear none of it. He sent orders to Richard Ewell to "assail the enemy's right" at daylight, and he ordered Jeb Stuart (who had finally arrived at Lee's headquarters early that afternoon) to operate on Ewell's left and rear.

Casualty figures for the second day of Gettysburg are difficult to assess because both armies reported by unit after the full battle, not by day. One estimate is that the Confederates lost approximately 6,000 killed, missing, or wounded from Hood's, McLaws's, and Anderson's divisions, amounting to 30–40% casualties. Union casualties in these actions probably exceeded 9,000.[58] An estimate for the day's total (including the Culp's and Cemetery Hill actions) by historian Noah Trudeau is 10,000 Union, 6,800 Confederate.[59] This is in comparison to approximately 9,000 Union and 6,000 Confederate casualties on the first day, although there were much larger percentages of the armies engaged the second.[60] Some estimates of total casualties for the day run as high as 20,000 and declare it the bloodiest day of the Battle of Gettysburg.[61] It is a testament to the ferocity of the day's battle that such high casualty figures resulted even with much of the fighting not occurring until late in the afternoon and thereafter lasting about six hours. By comparison, the Battle of Antietam—known famously as the bloodiest single day in American military history with nearly 23,000 casualties—was an engagement that lasted twelve hours, or about twice as long.[62]

On the night of July 2, all of the remaining elements of both armies had arrived: Stuart's cavalry and Pickett's division for the Confederates and John Sedgwick's Union VI Corps. The stage was set for the bloody climax of the three-day battle.[63]

Notes

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 21. Eicher, p. 521. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 55-81.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 21. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 26-29.

- Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 61, 111-12.

- Pfanz, Second Day, p. 112.

- Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 113-14.

- Pfanz, Second Day, p. 153.

- Harman, p. 27.

- Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 106-07.

- Hall, pp. 89, 97.

- Sears p. 263

- Eicher, pp. 523-24. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 21-25.

- Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 119-23.

- Harman, pp. 50-51.

- Eicher, pp. 524-25. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 158-67.

- Eicher, pp. 524-25. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 167-74.

- Harman, pp. 55-56. Eicher, p. 526.

- Eicher, p. 526. Pfanz, Second Day, p. 174.

- See W. Frassanito: "Gettysburg A Jounry in Time", pp. 174-176

- See W. Frassanito: "Early Photography at Gettysburg", pp.287-289

- See W. Frassanito: "Early Photography at Gettysburg", pp.289-294

- Adelman and Smith, pp. 22-23. Eicher, p. 527. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 177-83.

- Adelman and Smith, pp. 29-43. Eicher, p. 527. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 185-94.

- Sears, pp. 274-75.

- Adelman and Smith, pp. 46-48.

- Gottfried, pp. 205-206; Adelman and Smith, pp. 46-48.

- Adelman and Smith, pp. 48-62.

- Adelman and Smith, p. 134.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 33. Pfanz, Second Day, p. 152.

- Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 26-29. Eicher, p. 531.

- Sears, pp. 275, 286. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 246-57.

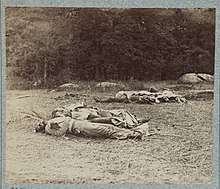

- Frassanito, pp. 315-18, states that the location of where this photograph (his plate "104b") was taken is unknown, although he groups it with others near the Rose Farm and confirms that the dead are Union.

- Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 252-61.

- See Frassanito "Gettysburg a Journey in Time".pp.212-213.

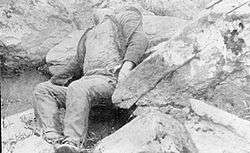

- The Library of Congress file for this photograph is entitled "Federal soldier disembowelled by a shell." Frassanito, p. 336, identifies it as "Dead Confederate soldier in the field at the southwestern edge of the Rose Woods."

- Eicher, p. 531. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 267-87. Sears, pp. 288-91, 303-04.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 31. Eicher, pp. 531-32. Sears, pp. 321-24. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 26-29.

- Eicher, p. 535. Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 31. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 390-400.

- Jorgensen, pp. 7-8.

- Sears, pp. 284-85. Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 32. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 313-17.

- Sears, pp. 298-300. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 318-32.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 34. Sears, p. 301. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 333-35.

- Sears, pp. 308-09. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 341-46.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, pp. 34-36. Eicher, p. 534. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 351-63.

- Sears, pp. 307-08. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 368-72.

- Sears, p. 346. Pfanz, Second Day, p. 318.

- Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 403-06. Sears, pp. 318-19.

- Eicher, p. 536. Sears, pp. 320-21. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 406, 410-14; Busey & Martin, Regimental Losses, p. 129. According to Busey & Martin, the 1st Minnesota had an effective strength of 330, but Sears and Pfanz state that only 262 participated in the charge on July 2. The total regimental losses for the Battle of Gettysburg, including Pickett's Charge, were 67.9%.

- Sears, pp. 322-23. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 387-417. Eicher, p. 536.

- Coddington, p. 459.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 36. Sears, pp. 323-24. Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 386-89.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, p. 37. Eicher, p. 537.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, pp. 40-42. Eicher, pp. 538-39.

- Pfanz, Battle of Gettysburg, pp. 37-40. Eicher, pp. 536-37.

- Sears, pp. 341-42.

- Sears, pp. 342-45. Eicher, pp. 539-40. Coddington, pp. 449-53.

- Official Records, Series 1, volume XXVII, part 2, p. 320.

- Pfanz, Second Day, p. 425.

- Pfanz, Second Day, pp. 429-31.

- Trudeau, p. 421.

- Trudeau, p. 272.

- "Ten Facts About Gettysburg". Civil War Trust. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- Eicher, p. 363.

- Sears, p. 342.

References

- Adelman, Garry E., and Timothy H. Smith. Devil's Den: A History and Guide. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1997. ISBN 1-57747-017-6.

- Busey, John W., and David G. Martin. Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, 4th ed. Hightstown, NJ: Longstreet House, 2005. ISBN 0-944413-67-6.

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Frassanito, William A. Early Photography at Gettysburg. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1995. ISBN 1-57747-032-X.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 – June 13, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932714-30-2.

- Grimsley, Mark, and Brooks D. Simpson. Gettysburg: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8032-7077-1.

- Hall, Jeffrey C. The Stand of the U.S. Army at Gettysburg. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-253-34258-9.

- Harman, Troy D. Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8117-0054-2.

- Jorgensen, Jay. The Wheatfield at Gettysburg: A Walking Tour. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57747-083-4.

- Laino, Philip, Gettysburg Campaign Atlas, 2nd ed. Dayton, OH: Gatehouse Press 2009. ISBN 978-1-934900-45-1.

- Pfanz, Harry W. The Battle of Gettysburg. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service and Eastern National, 1994. ISBN 0-915992-63-9.

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The Second Day. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8078-1749-X.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 0-06-019363-8.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

- Haskell, Frank Aretas. The Battle of Gettysburg. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4286-6012-0.

- Mackowski, Chris, Kristopher D. White, and Daniel T. Davis. Don't Give an Inch: The Second Day at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863—From Little Round Top to Cemetery Ridge. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2016. ISBN 978-1-61121-229-7.

- Petruzzi, J. David, and Steven Stanley. The Complete Gettysburg Guide. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-63-0.

| External image | |

|---|---|