Battle of Crevola

The Battle of Crevola was fought in the spring of 1487, between a marauding Swiss army (from the Valais and Lucerne) [2][12] and troops from the Duchy of Milan,[2] for the supremacy of the Val d'Ossola (Eschental) .

| Battle of Crevola | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Transalpine campaigns | |||||||

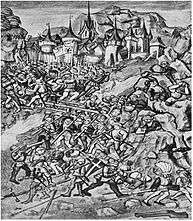

Battle of Crevola 1487 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Old Swiss Confederacy: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Renato Trivulzio Giberto Borromeo Gio. Pietro Bergamino [5][6] |

Albin von Silenen Jost von Silenen [3][7][8] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,200 Cavalry [9][10] 2,000 Infantry [9][10] total of 3,500 troops [11] |

6,000 Infantry [9][11] 1,000 Swiss joined from the Saluzzo Campaign | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown |

800-1000 killed [4][9][10][12] | ||||||

Prelude

In the year 1487, for unknown but petty reasons, Bishop Jost von Silenen entered into dispute with the Count of Arona[4], whose seignory was the Duke of Milan.[13] The Knight Albin von Silenen, brother of Bishop Jost von Silenen, was appointed the leader of this military expedition.[8] As soon as the Simplon pass was passable, the Swiss crossed into the Val d'Ossola; here they were joined by another 1,000 Swiss, who were returning from Savoy.[9]

Battle

The Swiss besieged Domo, occupied the castle of Mattarella, and terribly ravaged the impoverished valleys.[2] The Duke of Milan, however, ordered the Ossolani to keep the Swiss inactive with false peace negotiations, until the duchy could dispatch a sufficient army.[13] Once the troops were assembled, they were split into three separate corps under the command of Renato Trivulzio, Count Borromeo, and Gio. Pietro Bergamino.[5] The Swiss were once again marauding in the villages of the Valle Vigezzo, when they were assaulted by the ducal Milanese troops from three sides.[13] The Swiss formed a square and a murderous combat ensued, in which the Swiss lost 800-1000 men and all their baggage.[9][5] The rest of the Swiss troops were allowed to flee into the impassable mountain range.[12] The corpses of the dead Swiss were desecrated by the local peasants: the heads and fingers were cut off, the heads put on pikes and the fingers used as hat decorations.[9]

Aftermath

Further bloodshed was however prevented, when a legation of the Old Swiss Confederacy negotiated a peace treaty with the Duchy of Milan on July 23, 1487.[2][12] At ponte di Crevola, the Ossolani dedicated an Oratory to Martyr Saint Vitalis in honour and remembrance of this victorious battle.[5]

See also

- Battles of the Old Swiss Confederacy

References

- Historischer Verein der fünf Orte Luzern,Uri,Schwyz,Unterwalden & Zug (1838). Der Geschichtsfreund: 16.Band/Vol.14-15. Einsiedeln.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Iselin, Jacob Cristof (1742). Neu-vermehrtes historisch- und geographisches allgemeines Lexicon, Volume 3. Basel.

- Historischer Verein des Kantons Bern (1926). Archiv des Historischen Vereins des Kantons Bern. Bern.

- Vögelin, Johann Konrad (1855). Geschichte der Schwizerischen Eidsgenossenschaft: Vol I-II. Zürich.

- Bianchini, Francesco (1828). Le cose rimarchevoli della città di Novara: precedute da compendio storico. Novara.

- Ehrenzeller, Wilhelm (1913). Die Feldzüge der Walliser und Eidgenossen ins Eschental und der Wallishandel, 1484-1494. Zürich.

- Fink, Urban (2006). Hirtenstab und Hellebarde. Zürich.

- Büchi, Albert (1923). Kardinal Matthäus Schiner als Staatsmann und Kirchenfürst: Vol.1. Zürich.

- Furrer, Sigismund (1850). Geschichte von Wallis. Sitten.

- Rudolf, J. M. (1847). Die Kriegsgeschichte der Schweizer. Baden.

- Società storica lombarda (1889). Archivio storico lombardo: Giornale della Società storica lombarda, Volume 16. Milan.

- Fäsi, Johann Conrad (1768). Staats- Und Erd-Beschreibung, Vierter Band. Zürich.

- Pfyffer, Kasimir (1850). Geschichte der stadt und des kantons Luzern, Part 1. Zürich.